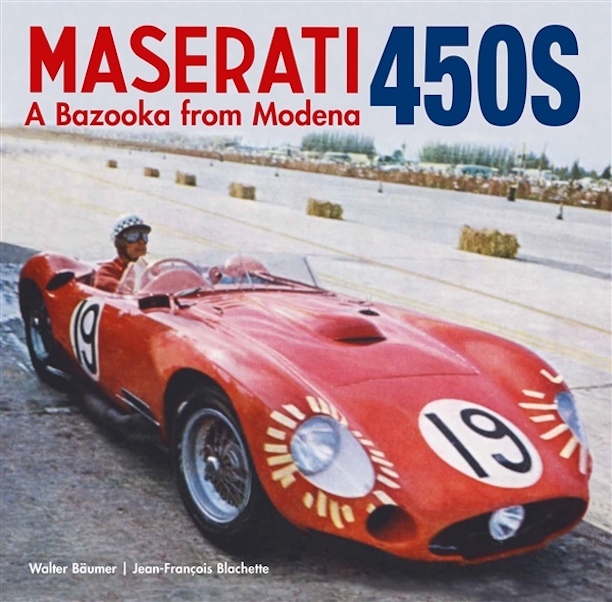

Maserati 450S: A Bazooka from Modena

by Walter Bäumer and Jean-François Blachette

“In 1957, with just four races in Europe in just one year, the 450S gained a reputation as an incredibly fast car, but it had an enduring reputation for being unreliable. This was only in a few cases due to the car itself, but to the rather superficial preparation in the factory or by the mechanics on site. The car became a giant and a failure at the same time. As a result, the easier to drive and less powerful 300S, which was also used in Europe for several years, became a racing icon and not the 450S.”

Add to that a very hefty price tag—but still too low for the company to make any money on this model—and you can see why only nine were produced 1956–1958, plus one prototype, plus one chassis cobbled together from two production cars, plus one single-seater specifically for the Monza 500-mile race. If you’re counting along, that makes 12 chassis, and all are discussed here.

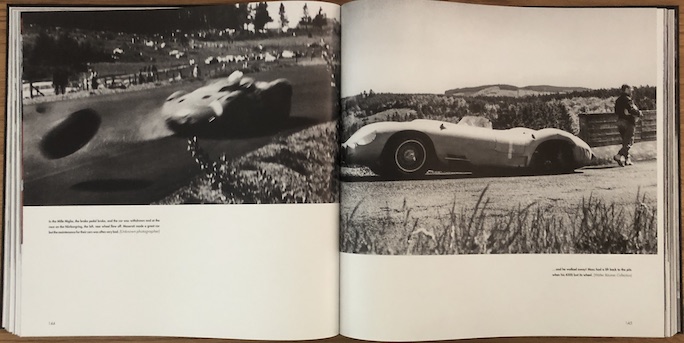

That reference to shoddy work at the factory is fully deserved. This is Stirling Moss losing a wheel at the Mille Miglia.

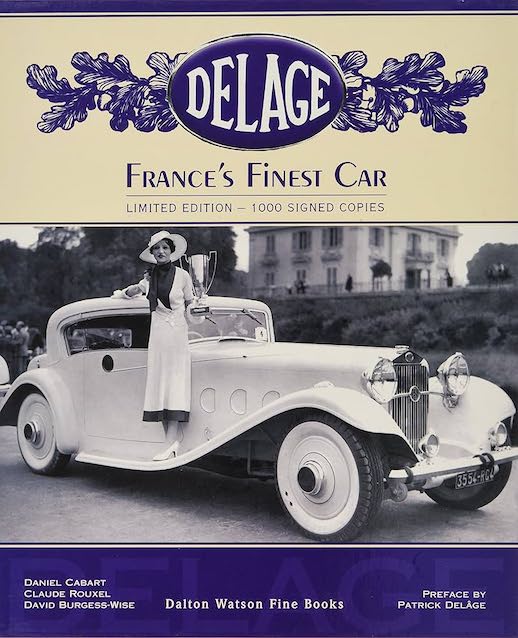

A book about this model by this author was just about inevitable because the oeuvre just wouldn’t be complete without it. Since first taking up Maserati matters in 2003 and then publishing his first book in 2008, about the 300S referenced above, German photographer and car enthusiast Walter Bäumer has established himself as a marque expert and this is now his 6th book about Maseratis of this era (that 300S book must be counted twice because it was reprinted ten years later having gained a second volume which made it altogether different from the 1st edition; incidentally, all are published by Dalton Watson). Both Bäumer and Blachette had high-level roles with the marque clubs in their respective countries, which translates to connections and access but also dials up the degree of scrutiny expert readers will bring to their work.

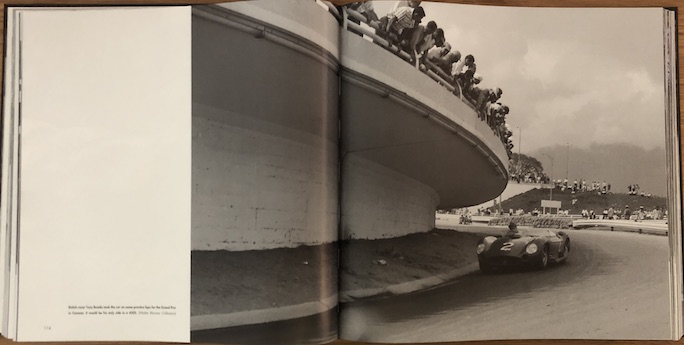

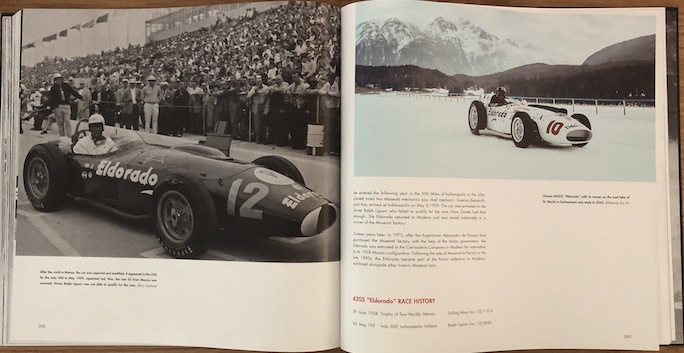

This is Carracas, Venezuela. Can’t you just imagine stuff falling out of people’s pockets?? Heck, people falling over!

If you have his earlier books this new one will right away have a familiar feel and MO. The latter means thorough individual chassis histories and extensive photo documentation, but also a fairly abrupt start to the proceedings that plunge the reader right into the thick of tech talk—no time for chit-chat such as explaining the eye-catching word bazooka in the title (you’ll have to wait 30 pages for a few words of enlightenment).

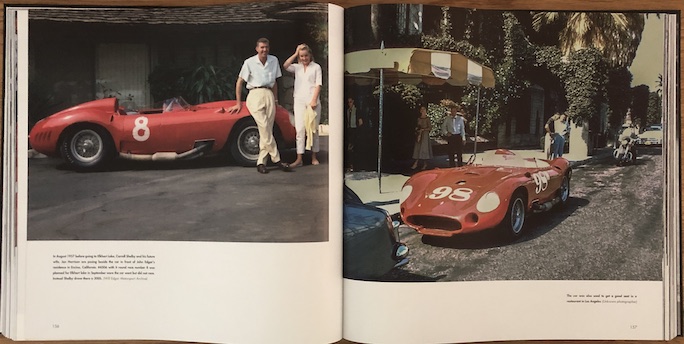

Surely you recognize the fella?! ‘Tis the chicken farmer hisself. But who’s the gal by his side? She would remain by his side—as the future Mrs. Jan Shelby neé Harrison.

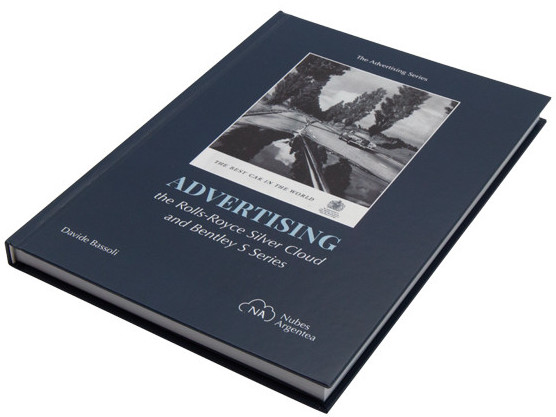

The photo on the right is by an unknown photographer and records an unknown moment. All the caption tells us it’s a restaurant in Los Angeles. What a sight/sound that must have been for patrons! You’d be right in thinking it’s usually the expensive machinery that gets parked right by the entrance: this car cost more than a new Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud! “98” may have been Shelby’s lucky race number but this car put him into hospital more than once. It is later in the book revisited in one of the two road tests excerpted.

Development of the 450S began already in 1954 with the specific intention of having a World Sportscar Championship contender. If you know your motorsports history you know that 1955, with the catastrophic accident at Le Mans, almost put an end to racing on public roads so further development of the motor was mothballed—and would have remained so if a wealthy American businessman with Indy ambitions hadn’t entered the picture. With this mise en scene the book begins, quickly sketching out design parameters and performance specs. Large, full-page photos and cutaways show what goes where, and you’ll probably quickly get the sense that you have not seen some/many of these images before. Another few pages touch upon competing machinery as well as the racing venues of the day, and then the individual 450S chassis histories begin, often augmented by lengthy quotes.

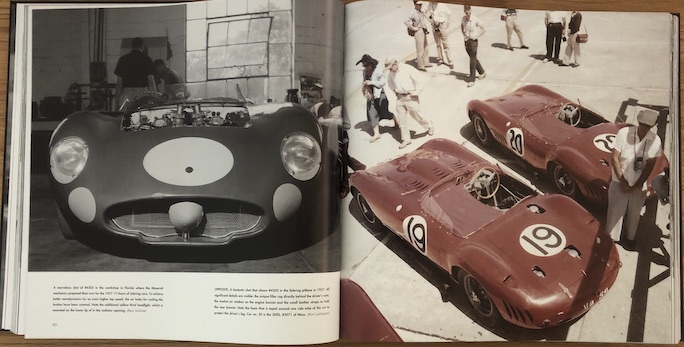

With so few chassis built, and 320 pages to play with, you’d be correct in assuming that photos play a large role, literally and figuratively (the book is almost 12 x 11.5″, same as the previous ones). They are well chosen and captioned, from a variety of sources, and about a third are in color, still quite the novelty at the time. Despite the large size, none appear over-enlarged i.e. pixellated. A few modern photos of restored cars round out the picture.

The one-off single-seater, once at Indy in 1959—and then in 2023. Do you know why it says Eldorado on it?

The book ends with 15 mini bios of key people in the 450S story, and the book has Indices, one of proper names and one of races by event and within that by chassis. And the review proper ends here, with a full-throated endorsement. Except it cannot end here because then it wouldn’t be a SpeedReaders review . . . so:

Obviously, 450S enthusiasts will know or have the Willem Oosthoek/Michel Bollée privately published 2005 book Maserati 450S: The Fastest Sports Racing Car of the 50s—A Complete Racing History from 1956 to 1962 (ISBN 978-2951364257), still easily found. It was and is a mighty good book, with a very similar page/photo ratio, and Bäumer mentions it several times. Inevitably, the passage of time makes possible some emendations to the received canon (cf. revised chassis identifications), and, as we will just about always say about a Dalton Watson book: they do earn the “fine” in their Fine Books tagline. But there’s another thing we have also always said, about Bäumer’s books: he does his own layouts. In the abstract, this should be neither here nor there because the publisher will still bring their normal processes into play—but it does change the dynamic. Long story short, typos catch your eye whether a book is cheap or expensive; in a $200 book they tend to rankle, especially when they appear to represent the sort of unforced error that is probably attributable to undue haste (or rewrites). Two examples: “He contacted Shortman to sell try to purchase the car” (p. 132), or on p. 194 someone is given a “ride from to the pit lane.” Are we selling or purchasing? coming or going? Sometimes, as in the first example, it changes the story. By the way, the “he” in that sentence is Joel Finn. Yes, that Joel Finn—prince among men, dearly missed (1938–2017), collector, historian, and writer of fine motoring books all of which you should strive to read.

On the right, two 450S cars, obviously. But look closely: one of them has several features unique to only it. Notice the 12 louvers on the hood of no 19. Obviously they expel hot air, so describing them as “air intakes” can’t be right. And on the next page they are described as “air out-takes” which is functionally better but a linguistic muddle. One can’t help but be reminded that English is not Bäumer’s mother tongue. For instance, one page (196) contains a construction that would be completely fine in German (“machte etwas falsch”) which he translates word by word into in English as “made something wrong”—which is not right.

Wir sind nicht amüsiert/We are not amused.

Copyright 2024, Sabu Advani (Speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

Dear Sabu,

I have not read the new 450S book yet, only the preview offered by Dalton Watson. Bäumer is not known for his willingness to submit to peer reviews, but in one particular case [apart from his English] he should have. It has been known for quite a number of years that the crashed Mille Miglia car of Behra was chassis 4501, not 4503, a car that appeared less than two weeks after the MM practice/crash at the Nürburgring [including travel time!] in essentially the same form in which it had won at Sebring in 1957. Timewise impossible. Yes, Michel Bollee/Yours Truly made the same error in our own book, some 20 years ago, but certain information from the factory archives was not known then. By process of elimination, it had to be 4503. I always had my doubts but could not prove it. Only after some financial incentives were paid was the factory historical department willing to submit build sheets, showing that the Zagato Coupe started life with a completely new chassis [not the rebuilt 4501 of Buenos Aires], with the number 4506. After the MM crash, in which 4501 was completely demolished, its chassis number was recycled to the new Zagato Coupe and 4506 was reused later on again for another 450S [the John Edgar car]. It is important information that has been around since 2016, so Bäumer turned out not to be so well connected with the various Maserati specialists/historians as claimed.