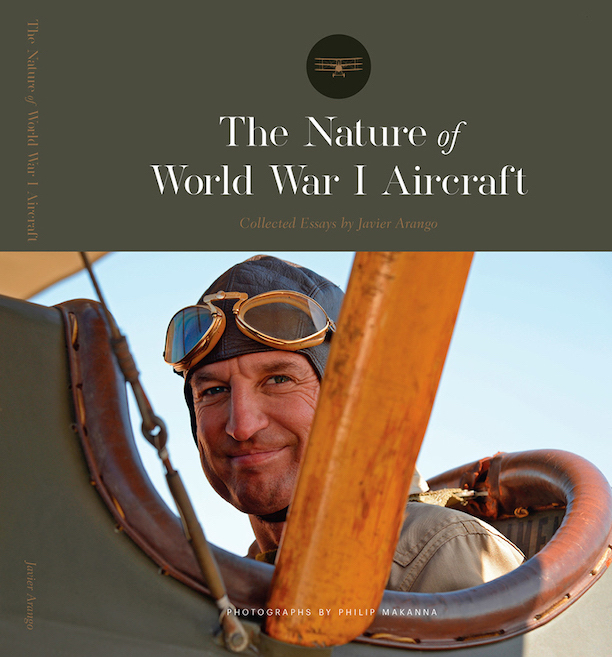

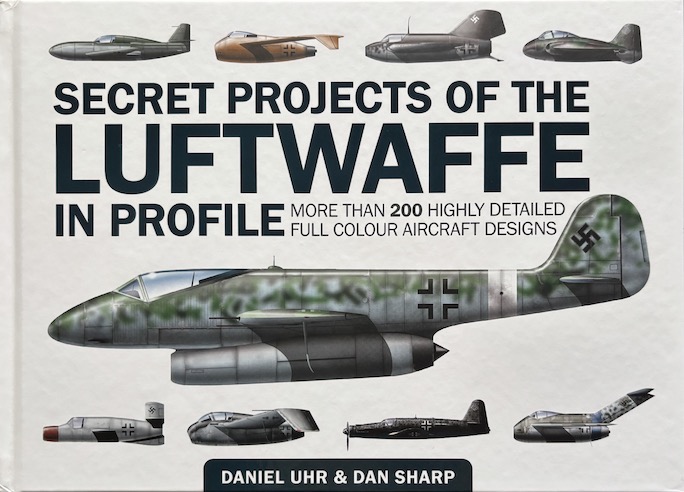

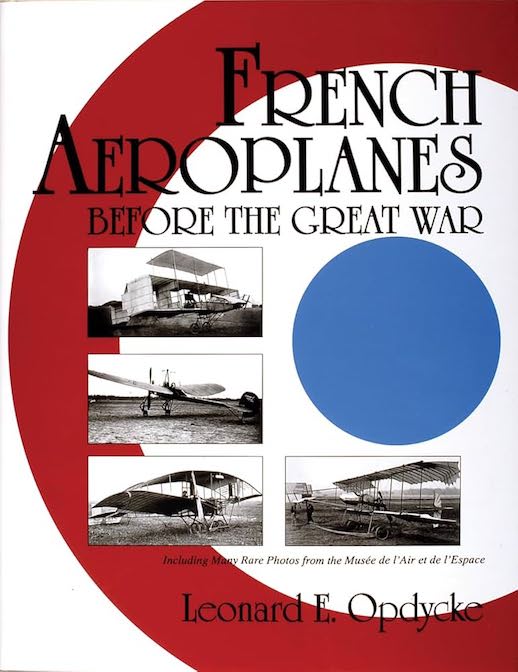

The Nature of World War I Aircraft, Collected Essays

by Javier F. Arango

“A Blériot does not take off. It levitates.”

Those who enjoy flying vintage aircraft are familiar with aeroplanes designed within the first three decades of powered flight. By then, fortunately, aviation nomenclature had been sorted out by a committee and some effort had been made towards standardizing control response and other aspects.

Even so, flying a vintage aeroplane requires its own mindset, quite different from that involved in operating a modern aircraft. A vintage pilot should mentally step back to prewar days of being content with lower speeds, watching the weather even more closely, and being wary of those large expanses of tarmac, unfriendly to tailskids or any hint of a crosswind.

Arango didn’t fly just to churn up the clouds but to wrest long-forgotten secrets from these vintage machines. The goal of his world-class collection was “to obtain and fly a discriminating selection of Fokker, Nieuport, and Sopwith models to complete a valid study of their evolution.”

Consider, then, the mindset needed in flying a machine dating back to the first decade of real progress in aircraft design and manufacture, before any thoughts of standardization, and when pilots were expected to be able to cope with the very real idiosyncrasies of individual designs. Without any established research into the theories of aerodynamics, the aircraft designers of the period based their decisions on rumor, intuition and practical experience, relying heavily on feedback from their end users—pilots (their own test pilots and those in the field) and mechanics.

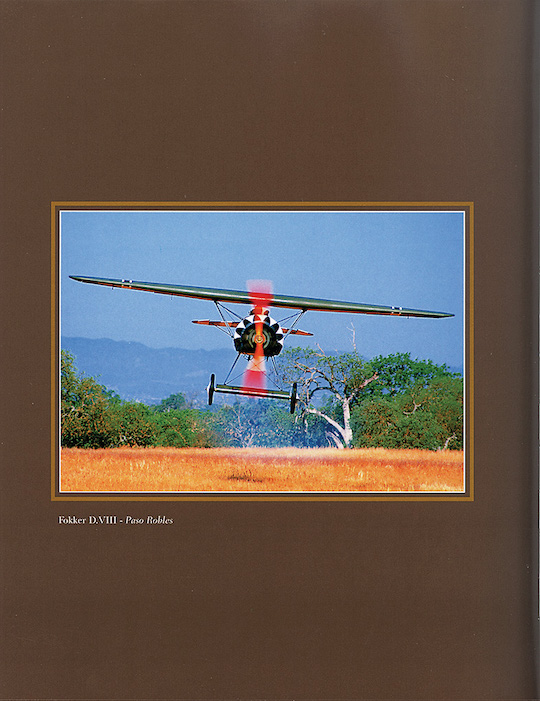

Born in Mexico in 1962, Javier Arango moved with his family to a ranch near Paso Robles, Central California, where with his father the acquisition of a Fokker Dr. I Triplane replica sparked a lifelong passion for aircraft of that era. That developed into the Aeroplane (sic) Collection of two dozen WWI (and a couple of earlier) examples, mostly reproductions powered by original or reproduction engines but also including an original Sopwith Camel and a Blériot XI, the latter built from drawings in Colorado in 1911 by two young brothers and restored to flying condition. The Camel and Blériot are now on display in the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

Born in Mexico in 1962, Javier Arango moved with his family to a ranch near Paso Robles, Central California, where with his father the acquisition of a Fokker Dr. I Triplane replica sparked a lifelong passion for aircraft of that era. That developed into the Aeroplane (sic) Collection of two dozen WWI (and a couple of earlier) examples, mostly reproductions powered by original or reproduction engines but also including an original Sopwith Camel and a Blériot XI, the latter built from drawings in Colorado in 1911 by two young brothers and restored to flying condition. The Camel and Blériot are now on display in the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

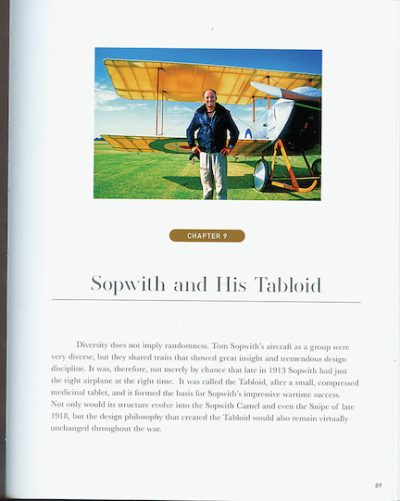

Arango wanted to build and finish his aeroplanes to be as authentic as possible. That meant not only using original drawings, construction techniques, materials, powerplants and systems as well as traveling to other countries to talk to others in the WWI aircraft community and research original colors and markings, but also trying to understand the technology of the time and the reasoning of those original designers and, perhaps to a lesser extent, the pilots who flew their creations. He paid most attention to two of the period’s most prolific designers and manufacturers—Anthony Fokker and T.O.M. Sopwith, one on each side of the conflict—and saw how fresh designs were emerging from them even as their previous models were just starting production.

Arango wanted to build and finish his aeroplanes to be as authentic as possible. That meant not only using original drawings, construction techniques, materials, powerplants and systems as well as traveling to other countries to talk to others in the WWI aircraft community and research original colors and markings, but also trying to understand the technology of the time and the reasoning of those original designers and, perhaps to a lesser extent, the pilots who flew their creations. He paid most attention to two of the period’s most prolific designers and manufacturers—Anthony Fokker and T.O.M. Sopwith, one on each side of the conflict—and saw how fresh designs were emerging from them even as their previous models were just starting production.

Over the years of this century Arango published articles and lectured on his favorite topic, backed by his expertise as an aerobatic, ATP, multi-engine, commercial jet, and glider pilot with instructor’s ratings and, on the academic side, training as a historian of science at Harvard University with an MBA and courses in celestial navigation. He published two aviation books with modern photographs by Philip Makanna as Ghosts of the Great War and The VanDersal Blériot. At the time of his 2017 death, caused by an elevator malfunction on his Nieuport 28 on a calm and clear spring morning, Arango was working on a third book that would describe and analyze the flying characteristics of each aircraft in his collection. (This book includes his Sopwith Camel analysis, using modern digital recording equipment.)

Antonieta Monaldi Arango, his widow, has gathered his writings, both published and unpublished, and with the help of many people including Peter Garrison and Philip Makanna produced this lavish and thoroughly professional publication.

These collected essays of Javier Arango contain a wealth of information, both gleaned from the many books written first-hand about the period and also the result of his own analysis and interpretations. He debunks a number of myths about the reasons behind the design and maneuvering qualities of such scouts as the Sopwith Camel, some 5500 of which were built and, despite killing more than 400 of its pilots in non-combat accidents, became arguably the most successful WWI fighter by shooting down about 1600 enemy aircraft. As a pilot who regularly flew aeroplanes ranging from 1911 to 1918, designed before any standardization of controls or handling characteristics, Arango is well placed to offer his own opinions.

For Arango’s careful analysis of aircraft construction more than a century ago and his interpretation of aviation history, quite apart from the book’s production qualities, The Nature of World War I Aircraft is highly recommended.

Limited to 1000 copies.

Copyright 2024, John King (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter