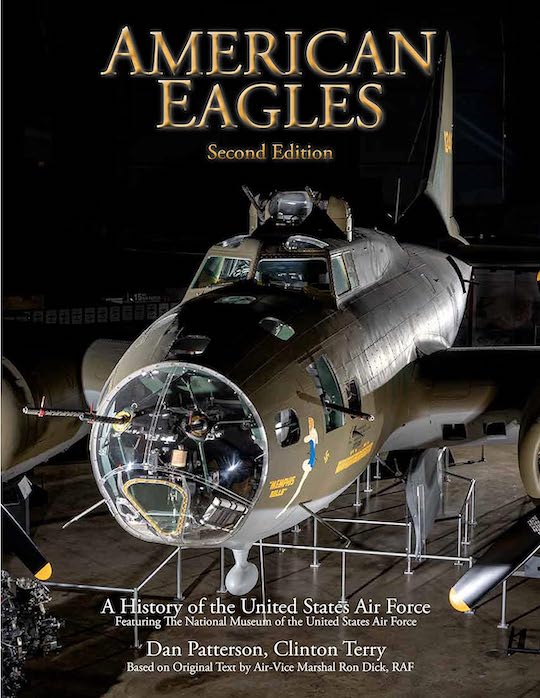

American Eagles, A History of the United States Air Force (2nd Ed.)

Featuring the Collection of the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force

Featuring the Collection of the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force

by Daniel Patterson & Clinton Terry

“One of the important backstories to the narrative is the need to keep military preparedness and political considerations independent of each other to the extent that is possible. In the wake of the World War, the United States chose a path toward isolation at the exact time the lessons of the war might have been directed toward investigating solutions to the problem of integrating air power into the American way of prosecuting war.”

This is a big and complex thought, and if it gave you the idea its writer must be a proper historian, you’d be right: Terry’s fields are the history of technology and the history of war, fields that exist independently of each other but also have an almost perverse connection. Something that will have complicated his work on this book is that it is a second edition of a book first published in 1997 by the late RAF Air Vice-Marshall (ret.) Ron Dick, and Terry’s brief here was to both largely preserve but also update the original text. One name common to both editions is that of photographer Dan Patterson who would follow up this first collaboration with Dick with another 17 joint books. In other words, a deep bench, yet the second edition is beset by snafus on the QC side.

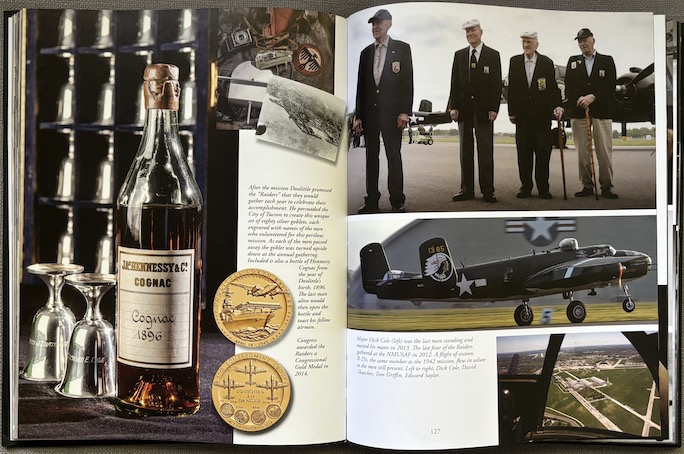

This spread about the Doolittle Raid really brings home that war is never really over for those who were in it. The Raiders had annual reunions and drank a toast from these 80 silver goblets (far left); each time another of the men died, a goblet was turned upside down—and the last man alive would open the bottle of 1896 cognac (the year of Doolittle’s birth) and say a last farewell to his comrades.

The excerpt above doesn’t say which World War is being talked about, and the thought could equally well apply to either (or the next?), but from the context it becomes clear that it is the Second World War that is being held up as an example, specifically that it took the US two years after Pearl Harbor before “air power could be said to have a meaningful impact.” And that lesson didn’t take at all, not for many years, as the book will make clear.

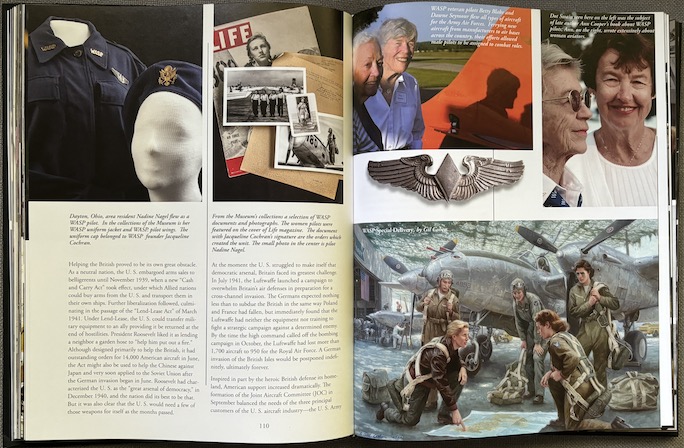

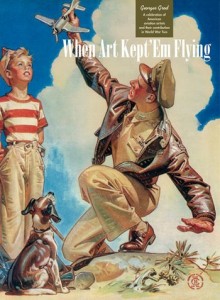

WASPS then and now. The painting is by Gil Cohen whose work is featured throughout.

While on the subject of WWII, one wonders if the words “American Eagles” in the title have to do with Dick’s RAF background because the three Eagle Squadrons (if that is indeed what was on his mind) consisting entirely of American volunteer fighter pilots attached to the RAF and RCAF would have a meaningful connotation for him even if they play no actual foundational role in the history of the USAF. (Moreover, under the U.S. Neutrality Acts of 1939 and 1940 those pilots stood to forfeit their US citizenship.) Formed in 1940/41 the Eagles would be turned over to the USAAF’s Eight Air Force in 1942, uncommonly as intact units rather than being broken up.

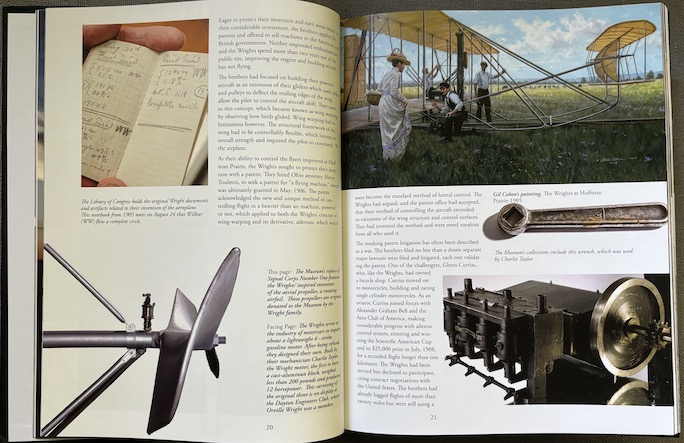

There’s a lot to see in this book; all these are artifacts from the NNUSAF, which are not all on display all the time. The Wright notebook, top left, is held by the Library of Congress.

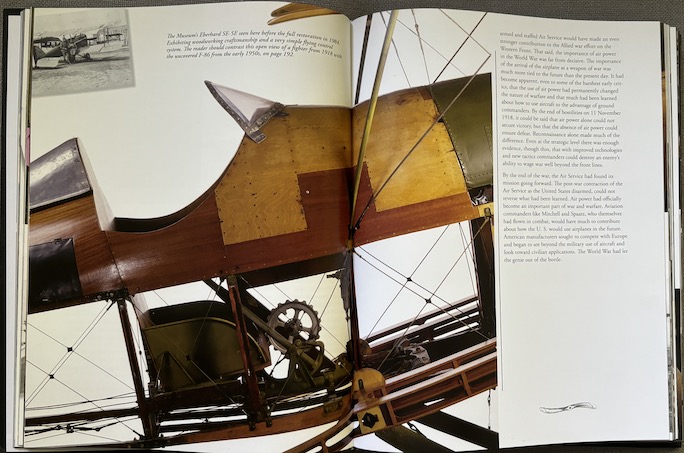

Definitely not something you can just expect to find anywhere: a 1918 Eberhard.

Dick’s first edition had been commissioned on the occasion of the USAF’s 50th anniversary, and this second commemorates the 75th. (Quick programming note: obviously military flying had been around before 1947 but that is the year the USAF was founded as a separate branch of the US military.) The new edition contains over a hundred fewer pages but more museum images (presumably to recognize its hundredth anniversary in 2023), and updated as well as additional text. What sets this book apart from your basic date-/event-driven history is the inclusion of a large number of featurettes of individual service members, often in a then/now setting. Then, too, there is the matter of the subtitle: while the main narrative is that of the development of powered flight, and specifically its application to devising means of carrying war to the enemy, the plentiful illustrations have plentiful captions and those often are specific to museum holdings (incl. artifacts other than flying apparatus) or practices. The NMUSAF, incidentally, is the oldest and largest military aviation museum in the world and has more than 360 aircraft and missiles on display.

One more item that is new to this book is the Foreword by NASA astronaut Eileen Collins (USAF ret.). Her focus on—peaceful—space exploration and human spaceflight as “the greatest mission” stands in almost jarring contrast to the second Foreword, carried over from the first edition, by American triple ace (WWII, Vietnam) fighter pilot and general Robin Olds whose take on optimizing warfare is rather more sobering but of course entirely fitting the subject.

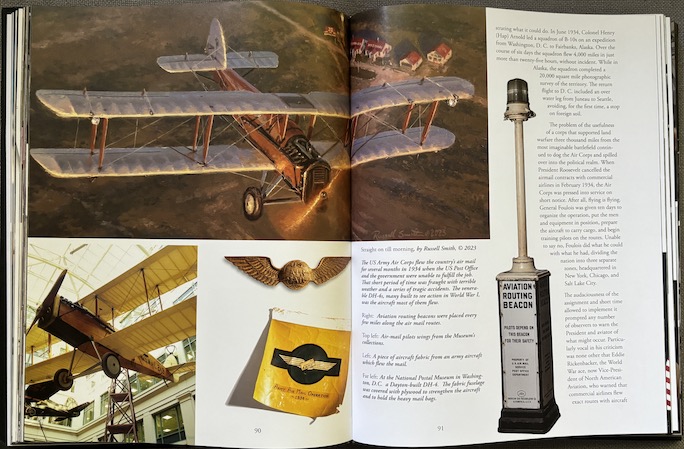

Those routing beacons, bottom right, were installed on the ground, in the 1930s, along mail routes.

Photographer Patterson mentions in his Foreword that the publisher imposed a “very ambitious timeline” and this brings the matter of the aforementioned snafus into play. Bear in mind that he refers to the book as “the official book for the U.S. Air Force’s anniversary.” You will have to be brimming with goodwill to forgive the onslaught of typos. We stopped counting after page 30, having encountered easily twice that number of gremlins, and stopped caring after about page 90. They range from the benign formatting error to the misspelling of proper names to entirely missing (also duplicated) words. “Failure to execute,” in military parlance. Dreaded words, words that send careers into the weeds. Clearly the grafting of new text onto old and the general reshuffling are the culprits; and probably no editor or proofreader to pick up the slack. And shame on all those reviewers who failed their readers by not calling it out, or worse, not noticing!

Commendably, someone did take the time to add cross references throughout the text which can of course only be done at the end, when the layout is locked in. Also, the book has a Bibliography which is as current as 2021 (dismissing “2979” as a typo, for Jablonski’s quite epic four-volume Air War of 1979) and there is a good Index, in tiny type but not wholly thorough probably because it is tailored to fit exactly the available space with no room to spare.

By 2024 parameters, this is a LOT of book for the money. However, the first edition (Howell Press, 978-1574270655) is still easily found, and larger, and considering that the new post-1997 material here is given barely 20 pages is not missing much.

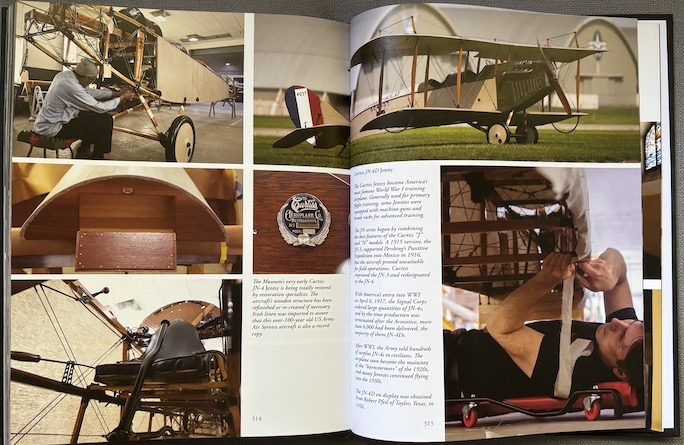

Two closing chapters look at the NMUSAF’s collections and restoration activities.

Copyright 2024, Sabu Advani (Speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter