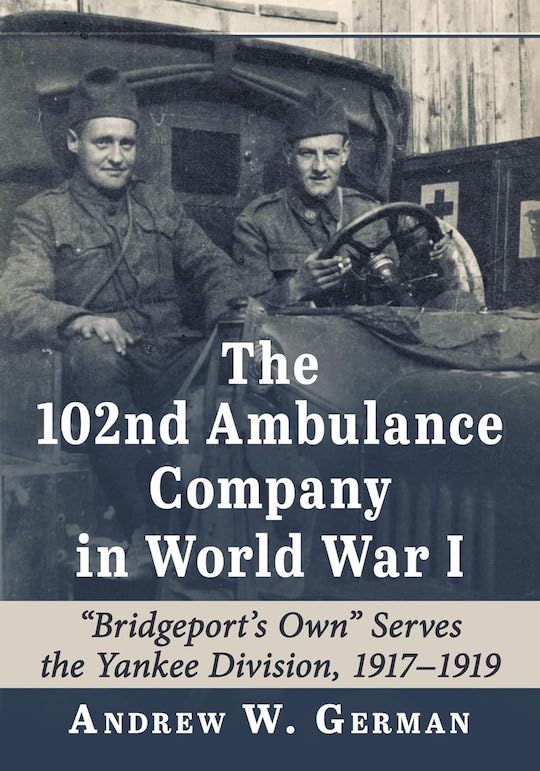

The 102nd Ambulance Company in World War I

“Bridgeport’s Own” Serves the Yankee Division, 1917–1919

by Andrew W. German

by Andrew W. German

Writers who have a passion for their subject usually convey that in their writing. That applies to this book twice over for, in truth, it has two authors—the one credited with its writing and the other that author credits in his dedication. The book’s author was born four years after the man he credits as its “true narrator” had died.

Andrew German writes in his prologue that he has always been interested in history, especially that of World War I. That interest eventually led him, perhaps due in part to his dad having been a neurosurgeon, to inquiring into the wartime hospitals and medical services during WW I and, in particular, those relevant to his home state of Connecticut. That is where he struck “gold” in the form of a detailed daily diary kept by Sergeant Leslie R. “Dick” Barlow, “who lived, recorded, and preserved” all that he saw, experienced, and did as part of The 102nd Ambulance Company in World War I.

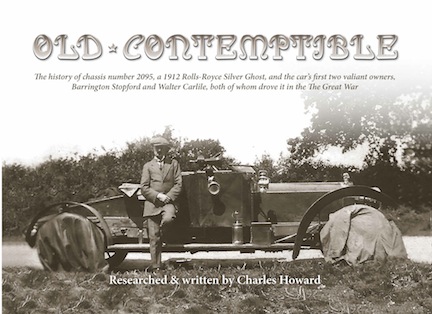

Barlow had had previous service in the National Guard when he enlisted, mustering in as a corporal, a few months later appointed sergeant. He kept and later published a daily diary. This photo is on the frontispiece and the book is dedicated to him, “To Sergeant Leslie R. “Dick” Barlow (1886–1946), the true narrator of this story, who lived, recorded, and preserved it.”

That 102nd was made up of men mainly from Bridgeport, Connecticut, hence the subtitle.

It makes for riveting, yet very troubling reading as it describes in detail the day-to-day life of those serving. It’s one thing to read in a general history about conditions and quite another to read the diary recounting each day’s activities and living conditions in the trenches and on the battlefields. And the 102nd experienced some of the worst as it was considered an elite group so put at the front. Thus even though technically non-combatants as Barlow observed in one diary entry, the Red Cross painted on the side of their ambulances was like a target to the Germans.

There was no relief from trying conditions even when not clearing a battlefield of wounded for obtaining food could be problematic. At one point German describes that, “Drums of food [are carried] from the ‘kitchens’ up to the trenches . . . sometimes left at cross roads in the hope it will reach some who need it but it is generally gassed so that it gases any who eats it.”

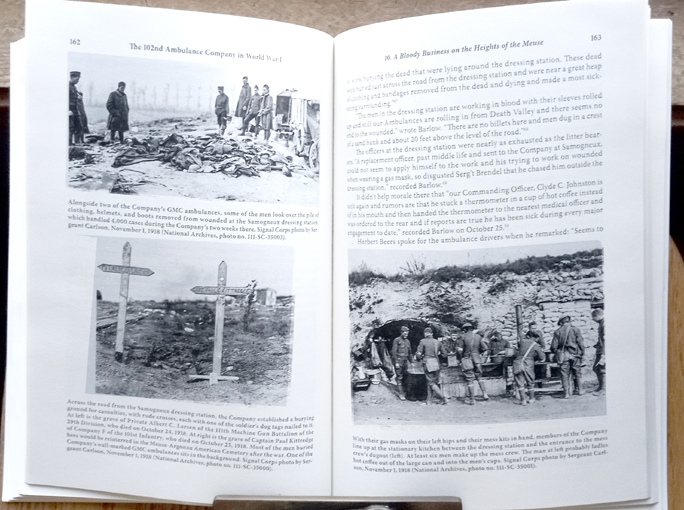

In both images on left hand page, you can barely make out two of the GMC ambulances used to transport wounded. In top image the items being looked at on the ground are clothing, helmets, and boots removed from wounded soldiers. Bottom is one of the burial grounds for casualties. Bottom right, men line up at a kitchen. All are wearing their gas masks on left hip as they are put their food in their mess kits. The man at furthest left likely is ladling coffee into their cups out of that large drum on the ground.

With seeming to be no end in sight two diary entries were particularly graphic. “Remarked Barlow, ‘This Division has been 208 days in the trenches and has been living on its nervous system for the past few months, the men’s bodies have wasted away and it seems as though the sight of many more legless, armless and sightless souls will snap that set of grey cords now worn to a thread so that none of us will go home human.’“

And, “After more than a week . . . under such lethal conditions, the Company was on the verge of physical and emotional exhaustion . . . Many have reached the point where they do not care if they are killed or not for no human being can stand this life.”

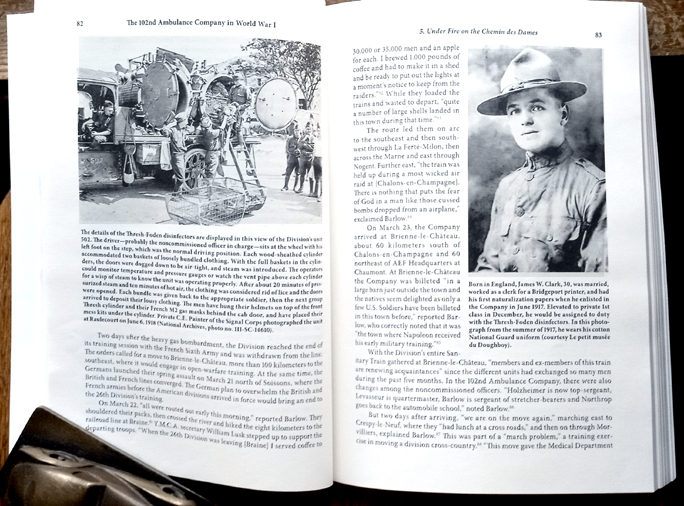

Portraits of various men in the company are throughout the book. This is James W. Clark. He’s dressed in his cotton National Guard uniform which was quickly replaced once the company arrived in France with clothing more suitable to the battlefield.

It’s the equipment on the left page that was finally brought into service to disinfect and delouse bedding, clothing, etc. by baking it with pressurized steam. The “bags” hanging from soldiers’ waists are actually their gas masks.

And then there were the vermin, lice especially, that infested everything. It wasn’t until the British Army made available Thresh-Foden disinfectors (seen at top left in above image) that there was at least temporary relief. Essentially this equipment was sheathed cylinders in which two baskets (seen on ground in front in above image) were filled with soldiers’ clothing, bedding, etc. Doors “dogged down tight” so pressurized steam could be injected to bake the contents at 238 degrees Fahrenheit for 20 minutes, followed by hot air to dry.

The book’s concluding chapter describes the six months following the Armistice that it took to finally get the men of the 102nd back home to Connecticut and the Postscript presents a synopsis of about twenty-five men of the company readers have come to know best, including Barlow. It is there we learn how he purposely preserved his diary, “not having the necessary means to have the History published I am doing what I consider most advisable, placing one copy in the Bridgeport [Connecticut] Library and one copy in the State Library.” From one, or perhaps both, additional copies must have been made as one is also in the World War I Museum in Kansas City.

The 33-page Appendix is a roster of those who made up the 102nd Ambulance Company. It’s not just a list of names either but tells a bit about each man. This is not a book you’ll read and then soon forget.

Copyright 2024 Helen V Hutchings (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter