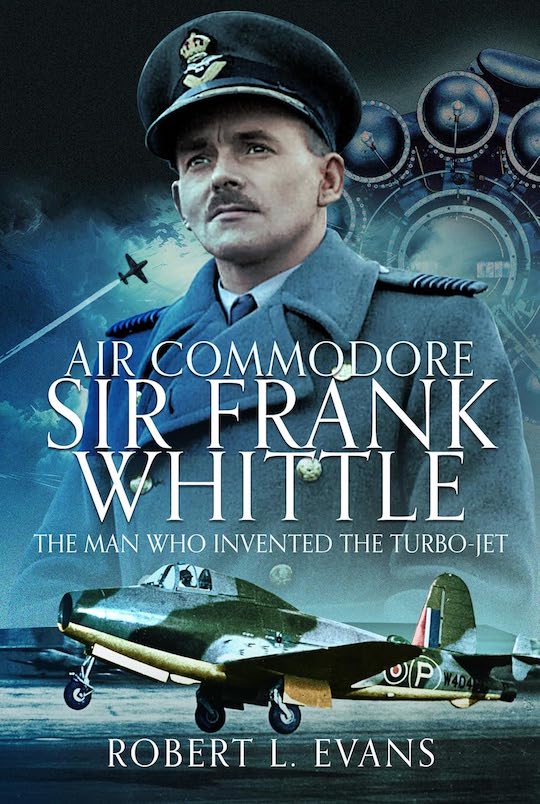

Air Commodore Sir Frank Whittle: The Man Who Invented the Turbo-jet

by Robert L. Evans

by Robert L. Evans

“He began by describing the challenges of developing power from piston engines at high altitude where the air density was much lower than near the ground, thus severely limiting the ability of air-breathing engines to develop sufficient power. He then went on to discuss the possibility of using a propulsion system that was completely different from anything else then known.”

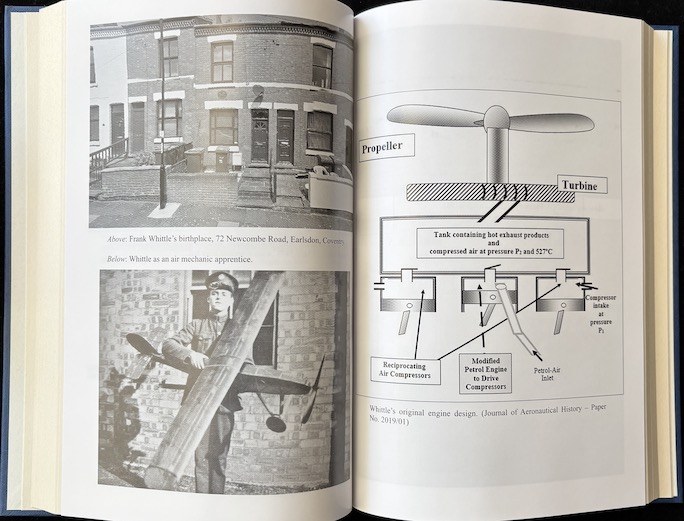

You’ll want to make a mental note that Frank Whittle was all of 21 years old when he submitted these words as part of his end of term thesis during officer cadet training. No one was interested. Already before then he had written letters to industrialists and academics to articulate his thoughts on a subject that had occupied his thinking for years. No one was interested. Now consider that as a 15-year-old whippersnapper he had failed the mandatory physical exam to get into aircraft mechanics training school so he bulked up his slender frame with protein powder and bodybuilding (and was wily enough to re-apply at a different recruiting station). Meaning? If there was an obstacle, he looked for a solution and that is why the Boy Apprentice rose to the rank of Air Commodore, becoming a skilled and dare-devilish pilot along the way, and created a whole new way to fly which, by extension, changed the way we live.

Even if you have no interest in the aviation side of jet engines, specifically gas turbine engines, there are plenty of technical concepts in Whittle’s work that have applications on terra firma: turbocharging, compressor performance vis-a-vis unsmooth airflow and, if you intend to go really fast, aerodynamic stall and more. Then there’s the whole business of the business side of this heroic/tragic figure missing out on crucial commercial opportunities, or the psychological aspect of being seized by the one Big Idea and seeing it early and pursuing it doggedly. In other words, there is much worth knowing about Frank Whittle. This new biography is written by an engineer so that flavors this particular take on his life.

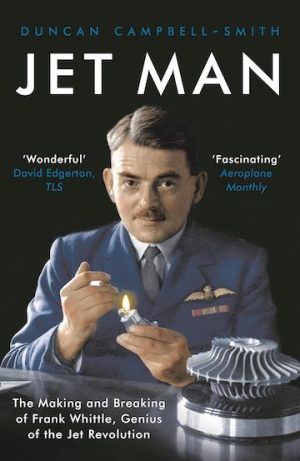

There’s easily half a dozen decent books about Whittle (1907–1996) and of course by him. Unless this is your first encounter with him you probably read the last noteworthy biography of the man, the quite monumental 560-page Jet Man: The Making and Breaking of Frank Whittle, Genius of the Jet Revolution (Apollo, 2021). Its author came from the Economics side of life so that was his overarching theme, also reflected in the phrasing of the title. While both books touch on many facets, for the reader with predominantly technical/engineering interests, the Evans book will speak a more familiar language. As Professor Emeritus of Mechanical Engineering at The University of British Columbia he is eminently qualified to deal with the hard science but one of his books also won a prize (2007) for “the best book on public policy published by a Canadian author” so he is just as good at dealing with the tension between theory and practice, the possible and the do-able.

There’s easily half a dozen decent books about Whittle (1907–1996) and of course by him. Unless this is your first encounter with him you probably read the last noteworthy biography of the man, the quite monumental 560-page Jet Man: The Making and Breaking of Frank Whittle, Genius of the Jet Revolution (Apollo, 2021). Its author came from the Economics side of life so that was his overarching theme, also reflected in the phrasing of the title. While both books touch on many facets, for the reader with predominantly technical/engineering interests, the Evans book will speak a more familiar language. As Professor Emeritus of Mechanical Engineering at The University of British Columbia he is eminently qualified to deal with the hard science but one of his books also won a prize (2007) for “the best book on public policy published by a Canadian author” so he is just as good at dealing with the tension between theory and practice, the possible and the do-able.

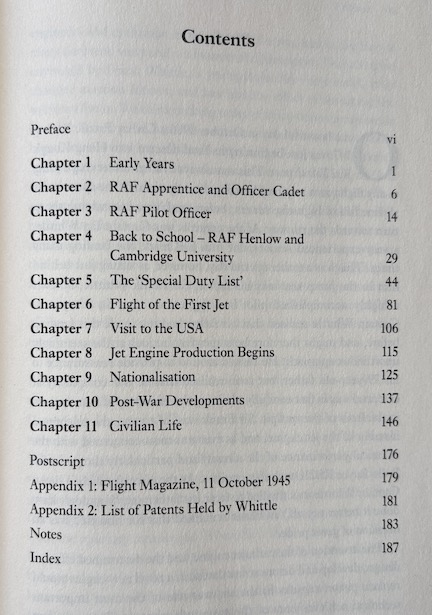

You’ll want to read this fine book more than once, and you’ll probably have to as the Index contains only names of people [1] and places and the Table of Contents gives no clue what specific events are to be expected in any one chapter.

You’ll want to read this fine book more than once, and you’ll probably have to as the Index contains only names of people [1] and places and the Table of Contents gives no clue what specific events are to be expected in any one chapter.

In the Preface Evans allows that he himself, half a century ago as a post-grad student at a newly-built turbomachinery lab at Cambridge, he and his fellow students had not really known much about the early history of the very subject they were studying—until Frank Whittle stopped by to officially open the lab that would henceforth bear his name. Evans became so absorbed by Whittle’s quiet competence that he resolved right then to one day write a book; this is it.

[1] We have to call it out because if we don’t someone will grumble that we’re asleep at the switch: German scientist H. v. Ohain is consistently misspelled “O’Hain” which is exceptionally odd because he and Whittle knew each other and exchanged correspondence over decades, correspondence that Evans must have seen.

Copyright 2025, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter