Cadillac Style: Volume One

by Richard Lentinello

Limited to 4500 numbered copies this is essentially a coffee table-type book that showcases an arbitrary selection of Cadillac and LaSalle models from some eight decades of production. It reasonably well represents the styling trends of Cadillac Motor Car Division.

What it is not is a detailed history of Cadillac’s styling department, the development of its styling trends, or its key players and decision makers, so in that regard the title could be considered somewhat misleading; as is the reference to “Vol. 1” because no others have appeared in the seven years since this one came out. (There is, however, a Corvair book.)

The format is essentially a series of 26 vignettes that begin with a short description of the selected car’s technical features followed by that car’s history as related by its owner and/or family members. Regrettably there is no Table of Contents (nor Index) but the cars are presented chronologically, ranging from a 1909 Cadillac Model 30 Demi Tonneau (above) to a 1993 Cadillac Allanté (here deprived consistently of the accent mark) convertible coupe.

Included along the way in their appropriate places are three LaSalles, Cadillac’s companion car, and two examples of the ubiquitous 1959, the only model year to receive such generous treatment. With the sole exception of a 1933 V-12 Fleetwood limousine, the author deliberately skips over the “heavy” multi-cylinder classics of the Thirties and focuses on the “bread and butter” models that generated the real showroom traffic and kept the factory occupied, if not exactly busy. They are to be covered in Volume 2, we are told in the coda. Except, see above.

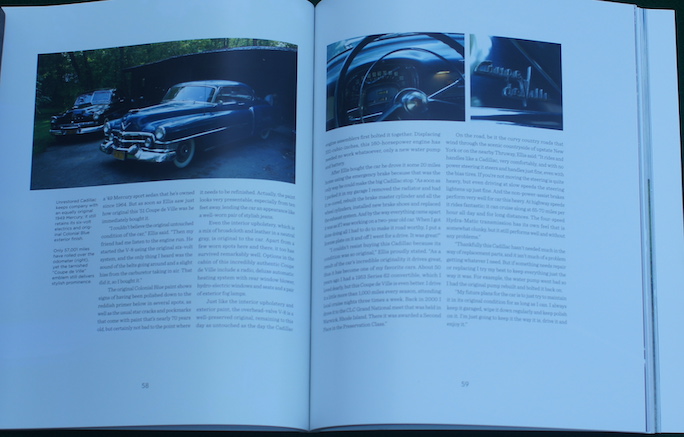

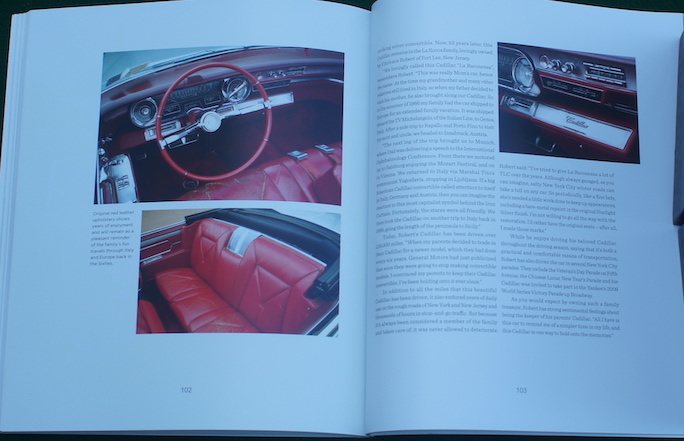

The vignettes typically start out with a short introductory page of text flanked by a full-page color photo, usually a full-view portrait of the car being described, but not always, and then two more pages of brief text and additional color photos. Several receive a six-page treatment, while the 1984 Cadillac Eldorado Biarritz, a modern classic if ever there was one, gets short shrift with only two pages of coverage. Unfortunately, it is in the photos where things get weak. The heavy art paper used reproduces color very well but many of the detail photos are small. Very small. And rather dark. In fact, a large percentage of photos, regardless of size, is so dark as to obscure details, especially in the unnecessarily too small detail shots. This gives the presentation an overall gloomy cast especially so for cars in a darker color scheme.

The 1951 Coupe de Ville.

Then, compounding the effect is the overabundance of “white space” or extra-large margins that might have been put to better use with larger detail photos. The overall dimensions are a generous 9½ x 11″ so there certainly is enough real estate to create better-looking and -working pages.

The author tells us in the introduction that this is the first of what he intends to be at least three volumes on this subject. While in many ways this is an impressive first effort, there is nonetheless substantial room for improvement. The overall idea bears merit, as the vignettes are quite entertaining. However, it is in the details of the execution where additional effort is needed. Thirty-five dollars is not an inconsequential amount to spend on a softcover book, not least if it is rife with obvious inaccuracies and factual errors. This sounds harsh, but consider this: In the very first vignette, on the 1909 Cadillac 30, George Selden is described as an engineer. But it is as a patent attorney that he changed automotive history, taking out a dubious patent on the internal combustion-powered automobile that threatened litigation against any manufacturer that did not pay him a license fee and royalties on every car they built. He did have a workshop behind his home where he spent his free time tinkering and invented several useful items over his lifetime but he was by no means an automotive engineer. By the time his patent was eventually declared invalid, after years of court challenges led by Henry Ford, he had pocketed hundreds of thousands of dollars in royalties.

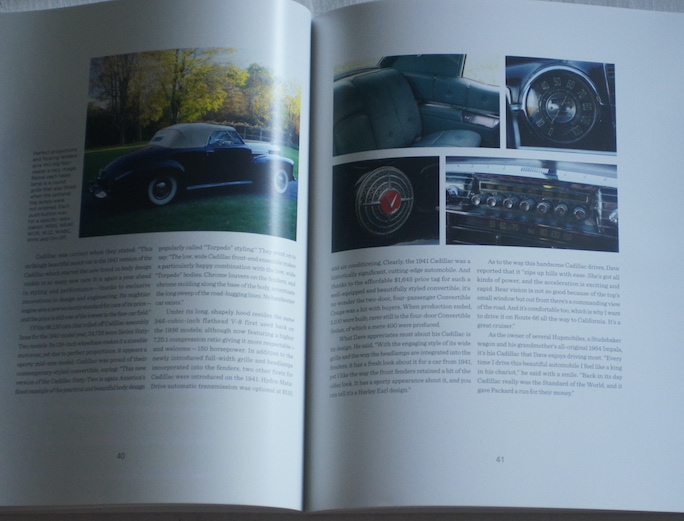

Then, there’s the 1941 Series Sixty-two Convertible Coupe. On p. 41 we find a group of four photos (above), a close-up of the speedometer, the radio, the fog light blanking plate, and a view of the left-hand rear seating area taken from the vantage point of the right front seat. The problem is, this seating area is not that of a 1941 Series Sixty-Two Convertible Coupe but a 1967 Coupe de Ville, which even the non-specialist is bound to notice because that same photo is then used again, some 60 pages later, in its correct context.

As to the 1947 Series 62 Sedan, Lentinello tells us (p. 46) that the 1947 body “is nothing more than a 1942 model but with restyled front fenders that flowed into the front doors instead of stopping abruptly at the door’s leading edge.” Nope, that styling feature was introduced across the line on all 1942s.

How about the 1949 Series 62 Sedan. This is one of my pet peeves. Lentinello writes, “So why does John prefer the stately looking four door sedan over more sporty models, such as the Coupe de Ville or the Sedanet.” No such thing as a Sedanet on a Cadillac (only Buick used that term) where it is—always—called a Club Coupe. It seems a great many Cadillac enthusiasts, particularly baby boomers, have become enamored with “sedanet” and use it frequently and incorrectly in conversation. It may sound more fancy than Club Coupe, but it be wrong. You won’t be making friends pointing this out at meets . . .

Now to the 1959 cars. Two of them. One should be more than enough as they already get a lot of ink in the literature. One school of thought considers them the epitome of Theatre of the Absurd on Wheels—even GM designer David Holls (d. 2000) kept mum for decades before admitting publicly he had anything to do with them. Enough said.

Lastly, although we could go on, the 1993 Cadillac Allanté. Per p. 124: “Built from 1986 to 1992, approximately 21,000 Allantés were produced during the car’s short seven-year production run.” Numerous readily available references show that Allanté production ceased at coachbuilder Pininfarina in July 1993 with the last car being finished in Michigan a month later.

Copyright 2025, Mark Dwyer (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter