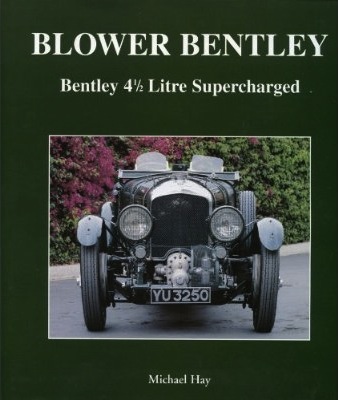

Blower Bentley: Bentley 4½ Litre Supercharged

The story of the Blower Bentley is in essence the story of two charismatic personalities: Henry Ralph Stanley Birkin and Charles Amherst Villiers. The former has come down to us as “Tim” Birkin, after a children’s comic book character “Tiger Tim.” The latter was well-born, the son of a Member of Parliament and first cousin to Winston Churchill. Four years separated Birkin and Villiers, Birkin old enough to serve—in Palestine—during the Great War, Villiers not, but still old enough to obtain a special apprenticeship at the Royal Aircraft Factory working on supercharging, an unusual opportunity for a teenager, even one with some limited prior experience at his school.

Their early adult life provides background to the motivation to supercharge and race the 4½-liter engine. Both found themselves involved with i/c engines at the very beginning of their careers, Birkin in racing, Villiers in supercharging for clients. Sir Henry was intensely patriotic, hence the “Tiger Tim” inspiration for his childhood nickname. Tim fell under the supercharging spell of Villiers in both boat and road competition some years before becoming a Bentley Boy. Thus, it was natural for him to turn to Villiers and supercharging as a way of increasing the performance of the four-cylinder engine. W.O. Bentley preferred two more cylinders (you can’t beat inches). Despite W.O.’s opposition, Birkin persuaded Woolf Barnato, who now owned Bentley Motors, to let him proceed with a supercharged version. All this is well-known. In this book, Hay provides from original source material the behind-the-scenes story, as much of it as can be retrieved at this remove.

This is considerable, adds color and personality to what we already know, and it is completely engrossing. Birkin’s early years are described: his marriage, the promise that ended his competition career, the divorce that involved the traditional private detective and contrived dalliance, and his second marriage. The effect of these episodes on his racing activities, marine and road, are adduced. Many names familiar to us from the “Bentley Boys” era appear very early in the tale as they emerge from pre-WW I motor racing and Great War aviation into the postwar scene, many of them drawn to W.O. Bentley and later Birkin. Notable among these personalities were Clive Gallop (rhymes with tallow) and Kensington Moir, the redoubtable K-M, adding a post-WW II perspective to 1930s Bentley lore. Amherst Villiers comes across as a prickly individual not above risking the appearance of self-aggrandisement. In this respect, the author’s impressions recall this reviewer’s visit, some 25 years ago, to Villiers at his cottage in west London with a suggestion that he write the definitive story of the Blower Bentley for the Review, the magazine of the Bentley Drivers Club which I edited. I immediately found myself discussing his fee, and as my budget for this purpose lay between zero and none, that was the end of the scoop. He was undeniably fascinating, with (he said) a girlfriend stashed on one of those Spanish Mediterranean islands, and a long-married sister named Veronica Milner on Vancouver Island. (On several occasions Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip were her house guests during Royal visits to Victoria, notably to the 1994 Commonwealth Games. She was described as a distant cousin of the Queen.) She died a few years ago; I never did look her up, a lacuna I have come to regret.

Having described the origins of W.O., Birkin and Villiers, the author next turns his attention to supercharging technology as it existed in those days, clarifying the distinction between a compressor and a blower and, of course, omitting altogether more recent developments such as exhaust pulse supercharging. Hay acknowledges his debt to the DIY guide published by S-A Design in the United States. In fact, he traces the origin of the Roots-type blower to the Roots brothers of Connersville, Indiana; their company still exists there! Hay devotes the whole of Chapter 3 to the mechanical and thermodynamic design of the blower that Amherst Villiers claimed to have invented. I once asked Hay if he thought that the 50 production blower cars required by the Le Mans regulations might have had the rotor lobe clearances eased, to make the car less fussy to set up in private hands; he thought not. What prompted my question was my first trick at the wheel of a Blower 4½; Briggs Cunningham’s chassis MS3941 had a very modest rice pudding factor—a measure of the ability of a car to pull the skin off a rice pudding—suggesting such opened clearances.

The following chapters 4, 5 and 6 describe the 1929 and 1930 racing seasons, and the Brooklands racing scene. None of this original source material has ever before been placed in a single volume, and this alone makes the book unique. In and out of these chapters the reader learns much about, inter alia the Hon. Dorothy Paget, a cousin of Whitney Straight. There is a strong social component to the narrative, feeding the reader’s curiosity about what made even fringe characters tick. Many mysteries of long standing are cleared up. During my collaboration with Stan Sedgwick that produced All The Pre-war Bentleys—As New, clear evidence of a fiddle relating to YU3250 was uncovered. It appeared that two cars had resulted from the evolution of Bernard Rubin’s 4½ from standard to the first Blower car, enough pieces being discarded during the evolution to be re-assembled into a second “ghost” YU3250. Hay disposes of this by careful analysis of the service records and contemporary racing reports: there was only one YU3250.

Again, Birkin’s death supposedly due to burns suffered in the 1933 Tripoli Grand Prix—driving a Maserati—is debunked and correctly attributed to malarial poisoning arising from sensitization to malaria exposure during his WW I service as pilot-instructor in Palestine. However, it was necessary to persuade Birkin’s insurers to pay up—rightly so, but for the wrong reasons—all explained. The post-Birkin narrative relates the Hon. Dorothy Paget’s return to horse racing and her increasing eccentricities; it’s difficult to decide if her grief over Tim was a factor or not, probably not. In 1968 Stan Sedgwick gathered the four team cars at Silverstone after weeks of painstaking correspondence with their respective owners. This gathering demonstrated without argument that during their racing careers, the team cars freely swapped many mechanical components, engines, gearboxes, in order to get just one of the cars to the start line. Herein lies the probable real reason for the relative lack of success of the Paget team: insufficient resources in money and manpower. All this is, again painstakingly, sorted out and fully explained in the racing chapters.

The post-Paget history of the team cars is accounted for, and finally a brief record given of every one of the 50 production Blower Bentleys, each—incredibly—illustrated with a photograph where one has been unearthed; Ch. 8 is virtually an illustrated Blower catalog. Michael points out that he has used mostly postwar photos to avoid overlap with better known photos previously used in his important and award-winning book Bentley—The Vintage Years.

There is a short index that appears to be unsatisfactory until it is realized that a comprehensive one would be the same length as the book; traditionally, an index is shorter than the main work. There are a very few typos that will pass unnoticed by most readers; an inverted apostrophe, for example. One is gratified by the use of reproduction rather than the misleading replica. A note on the dust jacket announces that this will be the author’s last book about vintage Bentleys. Oh dear—we’ve been through this before; let’s hope not. The lasting impression is of a driven passion sustaining the research that produced this monumental book .

Copyright 2012, Hugh Young (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter