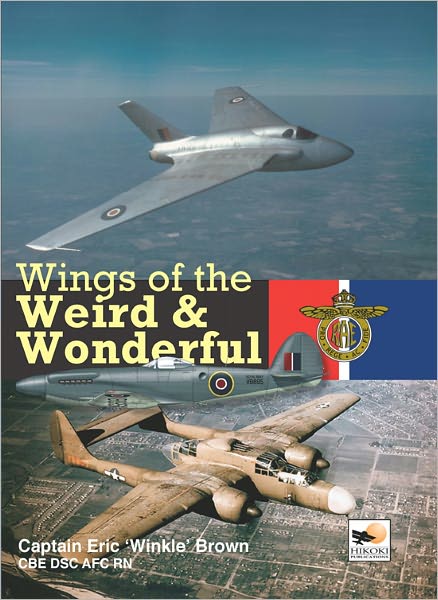

Wings of the Weird and Wonderful

“I have never been able to regard aeroplanes as inanimate objects, for they breathe life through their engines, and beauty and ugliness through their forms. They portray their characters through their controls, and can be as gentle as a lamb or as spiteful as a vixen.”

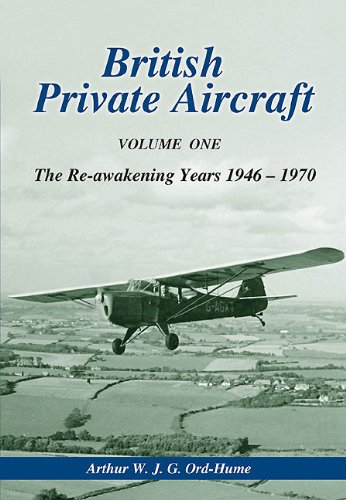

If you want to know how the hydraulically boosted flight controls in a WWII-era Lancaster I feel or if the footbrakes in a Winter Zaunkönig are effective, this is the book that’ll tell you. Over the course of three decades in the Royal Navy that made him the Fleet Air Arm’s most decorated pilot and put him into the Guinness Book of Records, the author has flown 487 types of aircraft (plus in many cases different marks of each) and here he discusses “from a totally subjective standpoint” the 53 of them he considers the “oddest and most fascinating.” They are mainly British and American ones, along with a few Japanese (German aircraft are the subject of a separate book, Wings of the Luftwaffe [2010]), and include rotorcraft and jets.

From taxiing and aerobatics to carrier landings and stall behavior, all the sorts of things only a pilot who can take an aircraft to the limit would know tantalize the reader, even the one who’s clutched a stick himself. Test-piloting from 1942 into the 1960s, after a stint as a combat pilot, Chief Naval Test Pilot Brown’s list of professional achievements and associations is long and distinguished—and enviable. Now in his nineties (b. 1919) he’s past the point of needing, wanting to blow his own horn but it is frustrating that he really says nothing about the circumstances that put him in the right places at the right times. All in a day’s work, eh? (Read his 1961 autobiography Wings on My Sleeve, updated several times in subsequent years.)

It is no wonder that this book has been reissued a number of times since its publication in 1983 and 85 in two separate volumes by Airlife. Presented in alphabetical order, each aircraft description begins with general commentary about Brown’s involvement with it and then, based on logbook entries he made at the time, focuses on specific behaviors. He can coin a phrase and doesn’t mince words—many of his pronouncements will stick with you! Some will probably surprise and a few perhaps annoy but his wide frame of reference makes him an utterly competent commentator. There’s at least one case in which the wordsmithing seems to have gotten away from him: “Unpleasant to fly, and with severe operational limitations which adversely affected its vulnerability” (p. 261). You know he means to say it made the plane more vulnerable but the word choice is ambiguous.

Many aircraft are accompanied by a feature called “Pilot’s notes” which is really nothing of the sort but rather one, sometimes several photos or illustrations of the cockpit layout with numbered callouts of flight controls. Alternatively there may be exploded views of the entire aircraft and there’s an occasional color profile. Where it is relevant to the story, derivatives are discussed, such as the Bristol Brabazon whose flight control systems were tested by Brown on the aforementioned Lancaster I.

Photo captions are short but specific. That photo credits are given in only a few cases is of no consequence to the reader but may frustrate the researcher who wants to move to a deeper level.

When your brain is tired from too many dry stats in other books, this one will perk you right up. As spry as Brown is even in his advanced age—and still active on the lecture circuit—it’s probably wildly optimistic to hope there’ll be more books like this! (Older books of Brown’s are being re-released, sometimes in expanded/updated form such as the 1980 bestseller Wings of the Navy, Carrier Testing American & British Aircraft, ISBN 978-1902109329 that came out in 2013.)

Copyright 2013, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter