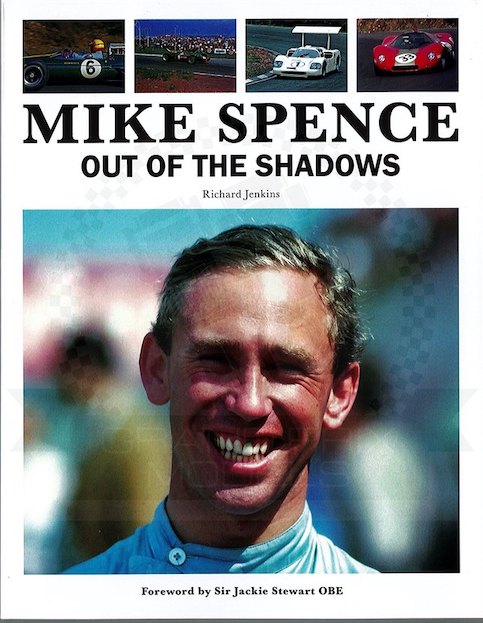

Mike Spence: Out of the Shadows

by Richard Jenkins

by Richard Jenkins

“He was a very talented driver, I think he was too nice . . . maybe lacking a bit of push and drive, just not ambitious enough.” David Hobbs

It wouldn’t be unkind to suggest that the main reason Mike Spence’s name has remained lodged in so many memories is because he died exactly one month after Jim Clark, on May 7, 1968. The fact that Spence was also driving a Lotus—in his case the revolutionary Type 56 turbine car at Indy—gave added resonance to the tragedy.

Richard Jenkins reminded us in his previous book that Richie Ginther was a more complex and nuanced character than the hippy drop-out that lazy journalism had often portrayed him as. So, has Jenkins pulled it off again? Has he succeeded in taking Mike Spence “out of the shadows”? The answer is yes, even though those with only a superficial interest in the sport might raise an eyebrow about whether the author’s hugely extensive research was merited. Because Mike Spence, to some eyes, was a driver who was a footnote in the history of Sixties motorsport, one whose talent and results were eclipsed by the genius of Jim Clark.

But this book is about much more than the career of Mike Spence, as the author’s forensic research has resulted in a mosaic of vignettes of so many figures in Sixties motorsport. And whilst the reader might expect the likes of Colin Chapman, Peter Arundell and Tim Parnell to be featured, there is huge selection of interviews, comments, and quotations from the dramatis personae of the Sixties’ scene.

This approach results in the book’s strongest and weakest points. The strength comes from first-hand accounts from Spence’s family, friends and rivals, some made in period and others obtained more recently by the author. The weakness—if it is fair so to term it—is that the amount of information can be almost overwhelming, with its content sometimes veering away from the book’s subject. Those already familiar with the era will find a tasting menu of new insights and recollections, but some readers will risk becoming bogged down in peripheral detail. This is a minor cavil, but I will confess that I did not find this book quite as unputdownable as Jenkins’s last book, the superb Richie Ginther – Motor Racing’s Free Thinker, and some defter sub-editing would have helped in places. But its 136 pages will become the definitive work on Spence, especially as so many previously unseen pictures are also included. I also appreciated the race-by-race career summary, something often lacking in this genre.

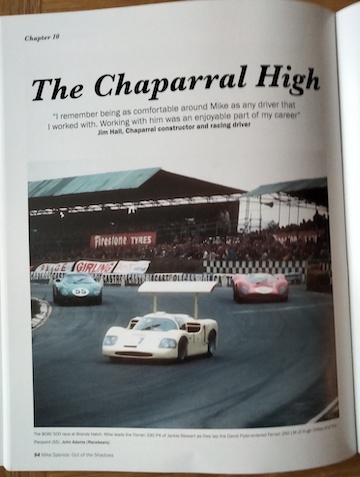

So what of Mike Spence the man? I learned of a comfortable, middle-class background in the South of England with a successful family business providing financial insulation. Not too many Britons were given a car for their 21st birthday in 1957, let alone a new AC Ace-Bristol. You can’t buy natural talent though, and Spence showed he had the right stuff by winning his first Formula Junior race in May 1960, only two months after making his debut in the Formula at the Goodwood Members’ Meeting. He progressed to Formula One in 1964, replacing the injured Peter Arundell in the Lotus 25 and 33 and he went on to score points by taking a sixth and a fourth place. But it isn’t unfair to say that Mike Spence never thrived as well as some of his peers in the rarefied atmosphere of Formula One. This quiet, unassuming man had neither the outright speed of a Clark, the bull-headed determination of a Brabham, nor the effervescence of a Hill (G.) or Ireland. He won two non-championship F1 races, at Brands Hatch and East London, and perhaps his approach to the sport was best epitomized in his comment to the Reading Evening Post in 1966: “Eventually every driver’s ambition is to be World Champion. But I always enjoy racing just for the fun of it.” Sir Jackie Stewart, who wrote the Foreword, called him “a  good driver, but not a great one . . . In Colin’s [i.e. Chapman] head everyone else (compared to Jim Clark) was second-rate.” Those judgments are in interesting contrast to Tim Parnell’s words: “Spence was, without any doubt in my mind, the most technically brilliant of all drivers.” But the fact that Spence drove superbly in the futuristic Chaparral 2F, taking that famous win at Brands Hatch in the BOAC 500, and that he was entrusted with the game-changing Lotus 56 turbine car at Indianapolis speak for the brilliance Parnell mentions. It is a bitter irony that the 56 was the car in which he was killed, another casualty in that cruellest of springs.

good driver, but not a great one . . . In Colin’s [i.e. Chapman] head everyone else (compared to Jim Clark) was second-rate.” Those judgments are in interesting contrast to Tim Parnell’s words: “Spence was, without any doubt in my mind, the most technically brilliant of all drivers.” But the fact that Spence drove superbly in the futuristic Chaparral 2F, taking that famous win at Brands Hatch in the BOAC 500, and that he was entrusted with the game-changing Lotus 56 turbine car at Indianapolis speak for the brilliance Parnell mentions. It is a bitter irony that the 56 was the car in which he was killed, another casualty in that cruellest of springs.

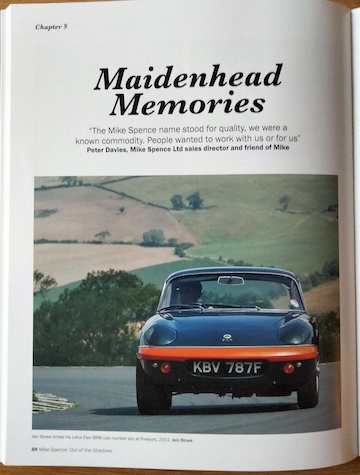

It is almost inevitable that, had he survived, Jim Clark would have continued to win Grands Prix in a Lotus, but it is much harder to predict what course Spence’s career might have taken if he hadn’t stepped into Greg Weld’s Lotus 56. His widow Lynne reveals how the couple were intending to emigrate to Australia in 1969, but I wonder how long that might have lasted. In chapter 9 (“Maidenhead Memories”) I had read how Spence had been little more than a sleeping partner in his garage business. I suspect that a life spent on a remote farm harvesting macadamia nuts might have had the same appeal to Spence as a South African BMW dealership had to Brian Redman in 1971. Very little, as Redman was back racing within months. From the extraordinary range of insights into Mike Spence’s personality that Richard Jenkins has assembled I suspect Spence would have remained racing, but not in Formula One. I think he would have joined that cohort of British drivers (of whom Redman is one) whose long careers played out in F5000, sports cars, Can Am, and Trans Am. Whether Mike Spence would ever have enjoyed the success of a Brian Redman, Jackie Oliver, or Vic Elford will forever remain open for debate. Was David Hobbs damning with faint praise in this review’s opening quotation—was he tough but fair or just plain unfair? It is to Richard Jenkins’ great credit that we now have so much material to inform that debate.

It is almost inevitable that, had he survived, Jim Clark would have continued to win Grands Prix in a Lotus, but it is much harder to predict what course Spence’s career might have taken if he hadn’t stepped into Greg Weld’s Lotus 56. His widow Lynne reveals how the couple were intending to emigrate to Australia in 1969, but I wonder how long that might have lasted. In chapter 9 (“Maidenhead Memories”) I had read how Spence had been little more than a sleeping partner in his garage business. I suspect that a life spent on a remote farm harvesting macadamia nuts might have had the same appeal to Spence as a South African BMW dealership had to Brian Redman in 1971. Very little, as Redman was back racing within months. From the extraordinary range of insights into Mike Spence’s personality that Richard Jenkins has assembled I suspect Spence would have remained racing, but not in Formula One. I think he would have joined that cohort of British drivers (of whom Redman is one) whose long careers played out in F5000, sports cars, Can Am, and Trans Am. Whether Mike Spence would ever have enjoyed the success of a Brian Redman, Jackie Oliver, or Vic Elford will forever remain open for debate. Was David Hobbs damning with faint praise in this review’s opening quotation—was he tough but fair or just plain unfair? It is to Richard Jenkins’ great credit that we now have so much material to inform that debate.

Copyright John Aston, speedreaders.info 2021

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter