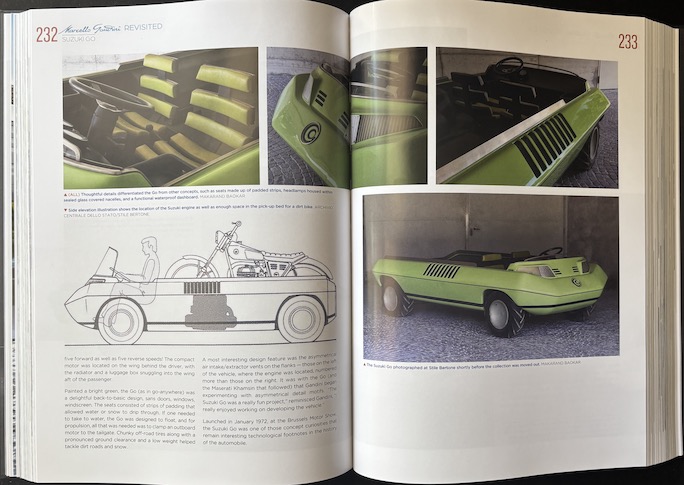

Marcello Gandini, Maestro of Design: Revisited

by Gautam Sen

by Gautam Sen

“And, as we worked on downsizing the book, we have added several more designs and illustrations which have been ‘rediscovered’ over the last few years. Marcello Gandini himself pointed out, ‘for every one design that made the light of day, there were three others that were rejected or forgotten,’ and we would like to add that for every one that is known, there may be as many as five others of Gandini’s design that remain unknown. Some which even he may have forgotten.”

Everything you need to know about this book is in that excerpt.

And just about everything should pique your curiosity. A book that is downsized but contains more material? A body of work that is not fully known and therefore not fully recordable? And why revisit a topic in the first place?

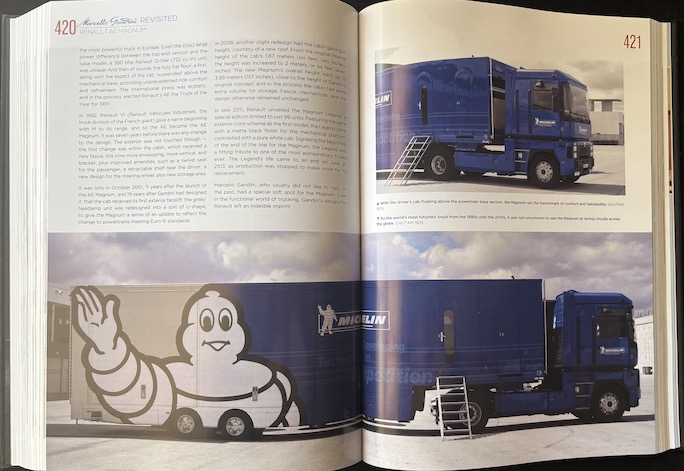

Everyone knows these icons: Countach, Miura, Strato’s, Montreal. But did you know that Gandini also penned the Renault AE Magnum (1990) below?

There are answers to all those things. It even answers a key question anyone who had been smart enough to buy the first edition—8 years ago, and obviously sold out—would have: was that edition “missing” anything that now necessitated a revision? Well, given the fact that Gandini was ever and only forward-looking, he did not “believe in maintaining records.” Also, he was entirely resistant to blowing his own horn, or others blowing it for him. So, yes, there is an incomplete record but the word “missing” implies a knowable, finite total so does not fit the picture.

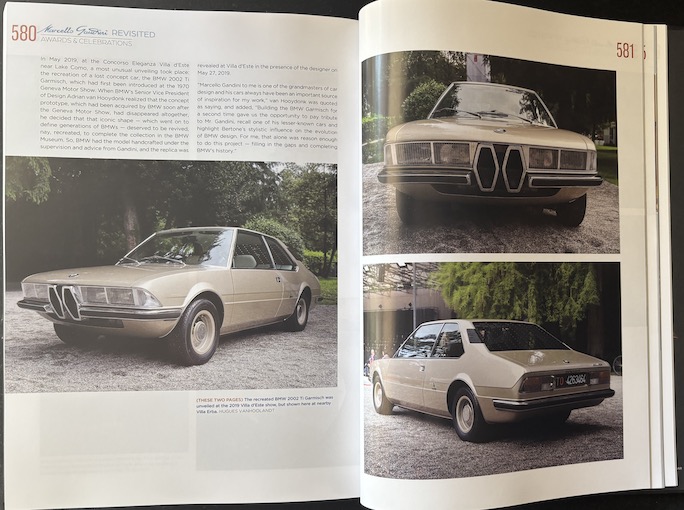

An example of something that was “missing” from the first edition (2016) because it wasn’t unveiled until 2019. The BMW 2002 Ti Garmisch concept car is a recreation of the 1970 Geneva show car that at some point had disappeared.

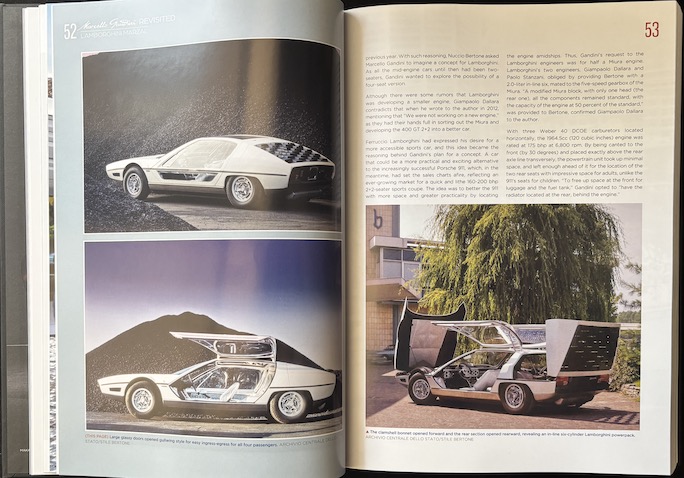

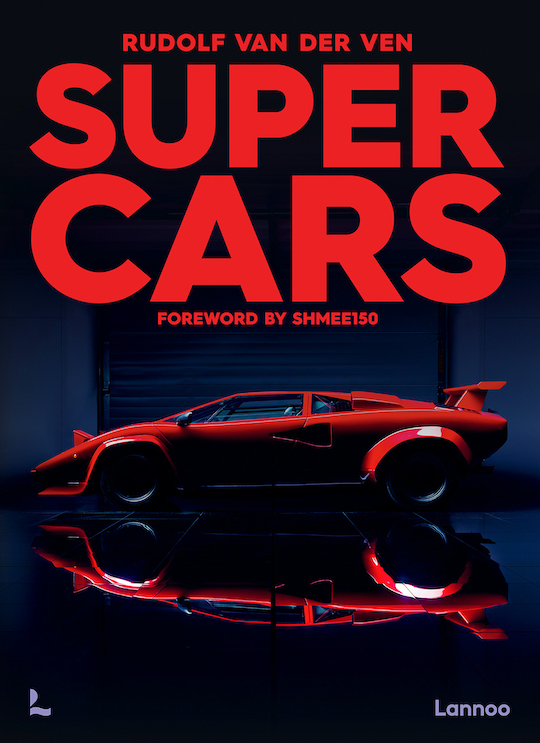

It is crucial to appreciate that it was anathema to Gandini to repeat himself, so he often considered even his most lauded, impactful current design passé while others were still mopping their brows over its newness. Perfect example: the famous 1966 Lamborghini Miura. The press fell all over itself. It was the fastest production car in the world. It did look breathtakingly beautiful. But to Gandini it represented “ideas and themes from the past” and he was keen to move on— next year’s auto show wonder was a design as otherworldly as a flying saucer, the 1967 Marzal which would excite him deeply enough to consider it a personal favorite. It looks otherworldly even today.

1967 Marzal. Lamborghini was looking for “a more accessible sports car” that could be “a more practical and exciting alternative to the increasingly successful Porsche 911.”

In a 2016 interview the then 78-year-old Gandini was asked if he would do anything differently if he could (Car and Driver, 12/16). Many things, he replied. The author of this book can relate—the whole reason the first edition had sold out was that the book had moved the needle, and while people were expressing interest in a new one they also bemoaned that the $295 price had been on the steep side even for Dalton Watson. The only way to achieve a lower price was to condense the original 800 pages into now 624. Savings: $130. Hooray.

But wait. How can a 200 pages shorter book contain an additional 400 hundred images and some 30-odd more projects? Kudos to the author and the publisher—and the designer!—for putting their minds to that. The new edition is not a “lesser” book than the bigger first edition, nor is it a supplement, nor a revision, and certainly and knowingly not a catalog raisonné; it is a fully rounded thing unto itself, conveying the core facts. Even if it contains fewer words it will make you fully conversant in such a multitude of Gandini projects that you will appreciate not just the diversity of his oeuvre but the skills that make his approach to design different from others. He was only in this thirties in the early 1970s when the top judges of Italian design were already praising him as “the most talented young car designer of his generation.” And he only got better. What set him apart was that he possessed an exceptional level of technical expertise which enabled him to holistically consider “the architecture, construction, and mechanisms of vehicles, rather than [only] their appearance.” He was an inventor, and his peers then and now rank him as a da Vinci-like figure. When you’ve digested these 624 pages you will struggle to come to grips with the dichotomy that he is “a master of design yet not widely recognized.”

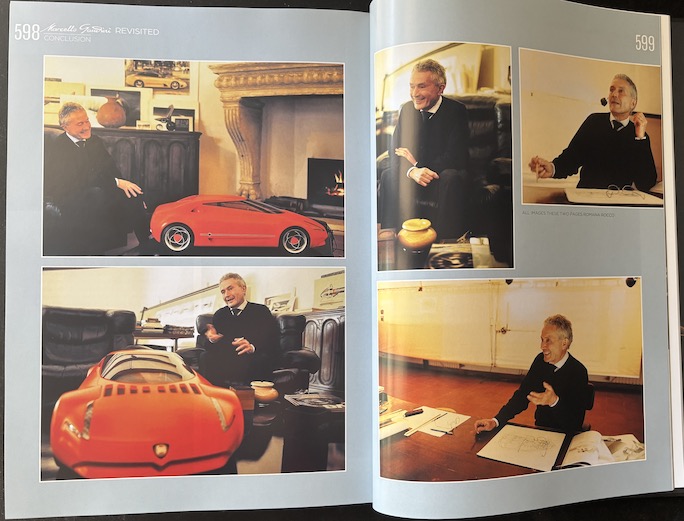

It should come as no surprise that author Gautam Sen holds Gandini, whom he knew personally, in the highest regard. Gandini took an active role in the shaping of this new edition but died before seeing it finished.

The book covers 135 projects from 1966–2011 (after which he was restricted by NDAs), “some of which seen for the first time in the public domain.” (Some of these may be on the fringes of the industry but they are nonetheless interesting and instructive, especially to the student of design.) They are presented in chronological order, in fact the Table of Contents shows the launch years. Between it and the exemplary Indices there is never any question as to what is included. If you have the first edition and you have the shelf space, adding the new edition is not redundant.

In the moving Foreword Gandini’s daughter writes:

“Looking back, I sometimes wonder if this way of living was wrong, as it disregarded image building, communication, and the pursuit of recognition. It left room for others to encroach and it sometimes allowed for unfairness. But in the clarity that came with his passing, I’ve realized that, yes, he was right.”

Not a dry eye in the house.

Gandini never stopped creating, and he never stopped not wanting to talk about himself.

Copyright 2025, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter