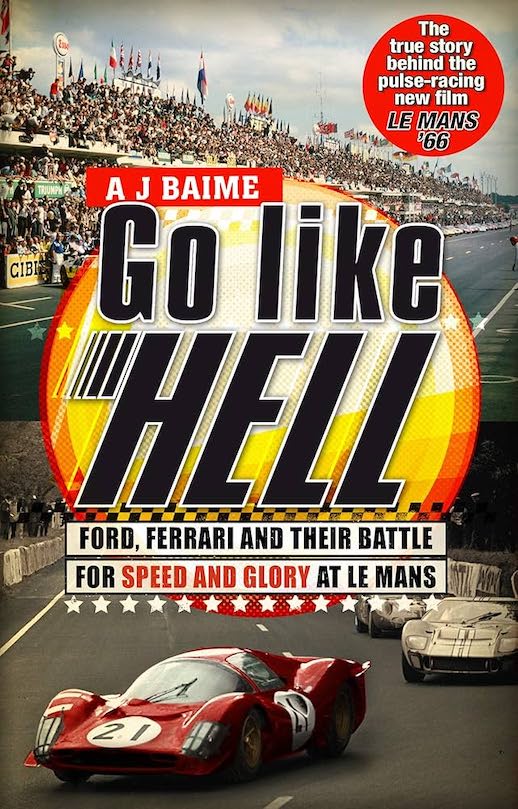

Go Like Hell: Ford, Ferrari, and Their Battle for Speed and Glory at Le Mans

A.J. Baime

A.J. Baime

“So spectacular was the finish, a photo of the three red cars speeding past the checkered flag at Daytona today graces the wall in Ferrari’s classic car restoration shop at the factory, blown up to nearly life-size.

But Enzo Ferrari’s sports cars were unable to continue their dominance. The cars did not win at Le Mans in June. A Ferrari never won the 24 Hours of Le Mans again.”

I am still not sure why exactly I bought this book.

It was due in large part that I was passing through an airport and looking for something to read. As a motorsports historian the book title obviously caught my eye but the fact that I had no idea just who the author was made me cautious. That Baime was identified as an executive editor at Playboy on the inside dust cover almost made me put it back on the shelf.

The book cover didn’t help.

True, one shouldn’t judge a book by its cover, but that it has a Ferrari (apparently the 330P3 of Jean Guichet and Lorenzo Bandini) leading the Ford GT Mark II of Ken Miles and Denny Hulme struck me as a questionable—or lazy—choice of photographs for the cover of a book on the subject of Ford beating Ferrari.

Ford won that year, 1966, not Ferrari, and in so doing added an important chapter to motorsports history. Of course, having a red Ferrari prominently on the cover probably attracts far more eyeballs than having a Ford GT leaving a Ferrari in the dust. If nothing else, this subtle bit of pandering to the Ferrari mystique—or simply “myth” which is probably more accurate—raised my eyebrow a notch or two. (Do note, however, that the 2010 softcover reprint, see bottom, did it better.)

Anyway, having time to kill, I bought the book and read it.

While I could, with more than enough justification, launch into a screed upon the evils of sportswriters sticking their noses into things of which they know not squat, I will instead shift the discussion towards a slightly different azimuth. If The Limit by Michael Cannell was what should have been a good story but was flawed by being told in a manner akin to a “made-for-television-movie” from the Seventies (not necessarily a negative criticism in all cases given that some such productions were excellent, cf. Steven Spielberg’s Duel) how does Go Like Hell stack up?

Indeed, given that this is another of the “good stories” from the era of the Sixties, one that has by now faded a bit from view, how does Baime handle the story? Putting aside the usual comments that are too often part and parcel of sports journalism—hyperbole, any drama milked for effect, an emphasis on characterization, a reluctance to let a good story be ruined by facts, and whatever qualifies as snappy prose. Of course, one is left with the awkward problem that journalists, including sportswriters, are supposed to be storytellers; that they are supposed to tell stories in such a way that people will read the stories and, hopefully, gain something from them. What that “something” might be is open to discussion, but as a minimum one supposes that the reader should not feel that his time spent reading was wasted. This sets the threshold for success rather low, and on that score, Baime delivers.

What Baime manages—and to give credit where credit is due, also Michael Cannell and Charles Leerhsen (Blood and Smoke: A True Tale of Mystery, Mayhem, and the Birth of the Indy 500)—is to lead readers to stories that they might not otherwise encounter, or consider worthy of their attention. While one is often loath to admitting the obvious, especially should one be a plodding sort of historian and researcher, Baime does tell his story in such a way as to allow one to begin to understand why it is often a challenge to sort out the act of sports-writing from that of writing about sports. They are quite different propositions and yet those differences can be very difficult to articulate.*

The era of “Total Performance” by the Ford Motor Company witnessed the presence of Ford—along with Mercury in some instances—in an almost staggering variety of automotive competitions: stock car racing, rallying, drag racing, touring car racing, grand touring racing in the form of the Shelby Cobra, record-breaking, the Indianapolis and the National Championship Trail, Formula One with its English Ford operation and Cosworth, and sports car racing in the form of the Ford GT project. While Ford did very well in some of these endeavors, it had only fleeting success in some and struggled in others.

If we frame any discussion of the Baime book using the criterion of wie es wirklich war, as we should, then once again we ought to first give (some) credit where it is due. While certainly not the sort of depiction of the era that a proper historian would write, Baime does give the reader an idea of how it was during the years that Ford and Ferrari squared off against each other for victory at Le Mans. That there were strong personalities in both camps, rife with conflict, tends to make the sportswriter’s task easier. This is not to damn with faint praise but simply recognition that such elements lend themselves well to such treatment.

It was, both at the moment and in retrospect, a time of melodramatic developments, something that was both operatic in its Sturm und Drang antics as well as often being pure soap opera. Above all else, it was actually an engaging drama, the sort of story in which both sides of the contest were neither angelic heroes nor diabolical villains. Well, some might make an exception for the latter when considering Enzo Ferrari.

Despite my many reservations about the presentation of the story, Baime does manage to convey some of the literal drama of the contest between Ford and Ferrari. That he does so by pulling in people such as Phil Hill, Carroll Shelby, John Surtees, and Ken Miles along with a number of others, so much the better. Indeed, it is often less what Baime writes as how he writes it. He captures much of the racing politics of the affair, which are often dismissed or overlooked by the Purists and Enthusiasts. If anything, this has made me waver in airily dismissing the book.

While not all that enthralled with Go Like Hell, I will say that I do find it the sort of book that I would suggest to someone curious about this era. It is a good introduction to the period, one that would, hopefully, lead to further inquiries, to include reading some of the other materials out there on this subject.

* Although William “Bill” Nack is a sportswriter, his book Secretariat reads as if it were a book written about a sports-related subject rather than a “sports book.” In this sense, Nack’s book is similar to Seabiscuit by Laura Hillenbrand, with the exception, of course, that she is not a sportswriter. Both books are about the sport of horse racing, somewhat similar in that they focus on a single horse and yet quite different in where and how that focus is handled. That said, both are excellent books, raising the admittedly low bar for the genre of sports-writing. Thus, perhaps, one begins to quickly sense the problems of how to articulate this issue regarding literary style and content.

Only the softcover version (right; Mariner Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0547336053) is currently in print.

Copyright 2016, Don Capps (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

I was given this book to review on my blog and I loved it.

A.J. Baime has done an outstanding job getting the story, and the intrigues of it all, across to the reader.

Once you start, it’s hard to put this book down.

The inside is well designed and easy to read.

The slip-cover certainly isn’t as good as it could be … kind of looks like a “Tide” logo slapped on top of what might be nice photos … it doesn’t do the book justice.

A “must-have” book!

Cheers!

Paul