Freedom’s Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II

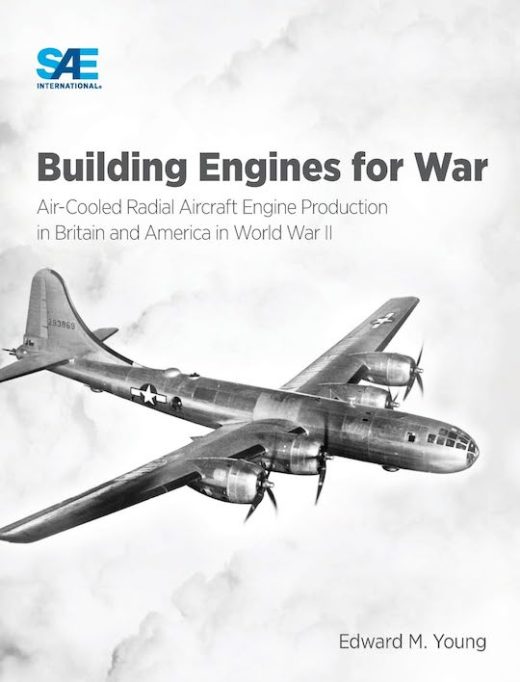

A B-24 Liberator flew over my house the other day, headed for the annual military-gear-and-airshow here in Stuart, FL. At 800 feet, with four 14-cylinder Wright Cyclone’s hitting their throbbing bass note, a B-24 sounds as all-American as a Harley Davidson V-Twin or a flat-head Ford. It is one spectacular blend of sight and sound—and a card-carrying relic of World War II

Pilots favored the handling of the B-17, we’re told. However, the B-24 flew higher, faster, and carried a bigger payload. More than 18,000 were built after mobilization began in mid-1940, and ultimately more were produced than an any other major combat aircraft in history. Jimmy Stewart flew more than 20 combat missions over Europe in the left-hand seat. George McGovern won the Distinguished Flying Cross piloting one on bomb runs, also in the European Theater of Operations.

Like most of the rest of America’s war arsenal, which was carefully sketched in the back of my geography book when I was in grade school, the names and profiles of the big bombers are now legend; we remember the movies they appeared in, and the heroic role they played winning the war. But the story of how they were designed and built, in impossibly large numbers has remained largely untold. In Freedom’s Forge, Arthur Herman takes care of all that. The story of the people, politics, and business skills that turned America into the “Arsenal of Democracy, will be a revelation even to war buffs.

How exactly do you tackle the problem of producing a Rolls-Royce Merlin aircraft engine, built entirely by hand as only English craftsmen can, with hand-fitted parts so that no two engines were identical, and adapt it to mass production? Why did Henry Ford refuse the job? Why did Alvan Macaulay of Packard take it on?

With steel in short supply, how does industry decide to expand aluminum production and adapt the lighter metal to uses that formerly called for steel? Is it possible to build a B-24 the way you’d build a Buick? How do you break it down into its 150,000 individual parts, subcontract the building of these parts, and then bring them together and into a flying machine?

In 1940 nobody knew the answer. In fact, nobody in the army or navy even knew how many guns, planes, or K-rations they’d need to fight a war. When Bill Knudsen finally compiled an answer, the numbers were frightening. American factories produced two-thirds of all military equipment used by the Allies in the war according to Herman: 286,000 planes, 8800 naval vessels, 5600 merchant ships, 2.6 million, 41 billion rounds of ammunition.

When the totals a broken down into daily production, the figures are stunning. Between Sept 1, 1939 when Hitler invaded Poland and September 2, 1945 when the Japanese signed surrender documents WW II had lasted 2195 days. On average, American industry produced 130 planes every single day. Production included everything from Stearman trainers to B-29s. In fact, production was low at first, and sometimes, as in the case of the B-29, grew slowly. But when war production began to gain momentum in 1942, records fell. Henry Kaiser’s shipyard in Richmond, California, starting from scratch in 1942, eventually was able to assemble and launch a Liberty ship in only 4½ days! American industry had become mobilized into a home-front fighting unit that never fired a shot but was as critical to victory as any commander in the field.

Herman builds his riveting story (no pun intended) on the backs of two 20th-century industrial Paul Bunyans: Henry J. Kaiser, the dynamo son of an upstate New York shoemaker who went on to build roads throughout the west, dam the Colorado and Columbia rivers, and ultimately build much of the merchant shipping that ferried troops and their equipment to the places they were needed; and William S. Knudsen, the Danish immigrant who arrived at Ellis Island in 1900 and went on to become Henry Ford’s production mastermind and after Ford could no longer tolerate his genius, went on to build Chevrolet into the world’s biggest automobile brand.

While America had been much involved in world affairs after WW I and all through the administrations of presidents Harding, Coolidge and Herbert Hoover, the country had become increasingly isolationist as the Great Depression deepened. Our fighting forces were mainly engaged in fighting for funding and chalked up few victories. With no market for planes, tanks, guns and ammunition, America’s aircraft industry shriveled. The only market for war materiel was off-shore and export of war goods was highly regulated. Not until May 1940, as Winston Churchill pleaded that western civilization’s survival was at stake was Roosevelt persuaded that Congress, and the country could accept a call for “readiness” in case war was thrust upon the country.

Author Herman uses the war as a metaphor aptly. Businessmen battle for war contracts, which in spite of excesses in WW I production, are let on a cost-plus basis, guaranteeing contractors a profit of 8%. The Truman committee, led by a feisty future president, fights waste, and war profiteering. Unions battle manufacturers in strike after strike. Government agencies seeking some sort of control over production attack the motives of private industry, which only wants to be left alone to fulfill contracts in its own way.

Herman’s home front battlefield is also littered with bodies. Businessmen, company executives, experts hired for their experience, were fired for their inability to meet the needs of ravenous bureaucracy, and media critics from Walter Lippmann to Mrs. Roosevelt. The supply of new experts, called up to replace the fallen, seems inexhaustible.

Many businesses thrived. Many business people became wealthy. A great many factories and facilities built at taxpayer expense for war production became part of the private sector at bargain prices after the war. Yet with all its faults, production miracles were achieved almost daily. American business managed to conspire to work together mass produce aircraft and other goods of mind-boggling complexity.

In the end, says the author, America had 25,000 prime war contractors and 120,000 subcontractors, often making products they had never dreamed of making. We readers are reminded so often this was possible only because American business, when unleashed from regulation and the interference of government, could perform miracles, that it seemed necessary to dig more deeply than usual into his background.

It turns out that in addition to his PhD from Johns Hopkins, and five other historical works to his credit, (a book about Joseph McCarthy, another about Mahatma Gandhi—a Pulitzer Prize finalist in 2009) Herman is or has been a visiting scholar at The American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank, “that prides itself on producing leading research (supporting its) . . . core beliefs: respect and support for the power of free enterprise, a strong defense centered on smart international relations, and opportunity for all to achieve the American dream.”

Freedom’s Forge survives its conservative leanings, however, because as far as I can tell it is a story that hasn’t been told before, and not incidentally because it is an as exciting to read as any battlefield story.

Copyright 2012, Arthur Einstein (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

AN EXCELLENT REVIEW OF A FASCINATING EXPOSE OF AMERICA’S ABILITY TO PRODUCE. AS IT WAS ONCE SAID “WHEN THE GOING GETS TOUGH, THE TOUGH GET GOING”. CERTAINLY AMERICAN INDUSTRY DID EXACTLY THAT COMMENCING IN THE LATE 1940s AS THE LIKELIHOOD OF OUR BEING INVOLVED IN WWII BECAME APPARENT. WE CAN RIGHTFULLY BE PROUD OF THIS CHAPTER IN AMERICAN INDUSTRIAL HISTORY.