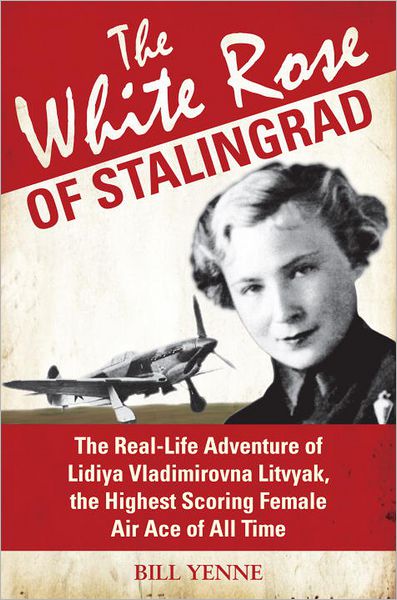

The White Rose of Stalingrad

The Real-Life Adventure of Lidiya Vladimirovna Litvyak, the Highest Scoring Female Air Ace of All Time

“As with the Amelia Earhart story, that of Lilya Litvyak has many layers of complexity. On August 1, 1943, Litvyak had fallen into oblivion, and that is where she would remain. As with Earhart, she slipped through a wrinkle in the fabric of time and space, and she never returned. The important thing about the remains of the young woman found on that day in 1979 is not so much whose they were, although that would have been very meaningful, but what they meant.”

Even if this story were pure fiction you’d want to read it, not least because author Yenne can turn a phrase. His rich, novelistic approach will often enough exasperate the reader who “just wants to get on with it” but there is craft and deliberation and a sense for the dramatic arc here, and it should neither be taken for granted nor be unappreciated.

When it comes to hard dates, it seems the only one that is not in dispute is Lydia “Lilya” (Lily) Litvyak’s date of birth. How many solo victories (between 8 and 13), how many shared (2? 4?), how many combat missions (66?), which German pilot shot her down, when/where she died—if in fact she died—those are all nebulous. One day, a few months shy of her 22nd birthday she disappeared into the clouds during a dogfight, smoke pouring from her plane. No one saw an explosion or a parachute, she just never returned. Wherein lies at least some of the answer for the prolonged lack of official recognition accorded her.

The various warring nations applied different criteria as to what constitutes a “kill” and, therefore, makes an ace but no matter how you slice it, Litvyak is one of only two recognized female Soviet WWII aces, alongside her close friend and flying partner Katya Budanova to whom are ascribed 11 kills. So much for the easy part of the story.

Yenne is probably right in assuming that the Litvyak episode is not widely known which is exactly why we have to step on the brakes for a moment. He presents here a fully fleshed out, plausible, even compelling scenario. But at the same time his book came out (Feb. 2013), another one was being published that interprets the scant facts differently. That is Gian Piero Milanetti’s Soviet Air Women of the Great Patriotic War, A Pictorial History (ISBN 978-8875651466). The reason for the disagreement is which sources are used—and believed. In his Epilogue Yenne addresses the issue of separating fact from myth himself, in a neutral tone, and while it is clear that he is not alone in the conclusions he draws it may well be lost on the impressionable or hasty reader that there is valid reason for doubt. What is interpretation to one is outright spin to another; already the book’s title may be seen in that light: the Soviets called Lilya Litvyak “the white lily” all along, after her nickname and the lily she used to paint on her airplane; “rose” was first a German and then a generally western corruption. So, treat this like a court case in which Yenne is representing one particular and not a universal point of view.

There are, though, universal aspects and values to the Litvyak story that are pertinent and true and moving regardless of who saw/heard what/when or which faction’s propaganda machine appropriated Litvyak for its purpose. And regardless of where Yenne comes down on the veracity of his sources, he presents a sincere account of the dreams of a young girl, her pain at seeing her father’s name besmirched by the regime, the promise of freedom—figuratively and literally—in spreading one’s wings and become a pilot, her patriotic musings, love of country/fear of the enemy, her willingness to stand up to gender clichés and still remain resolutely feminine, and many other personal—and universal—human stirrings. This story, and Yenne’s telling of it, will move you.

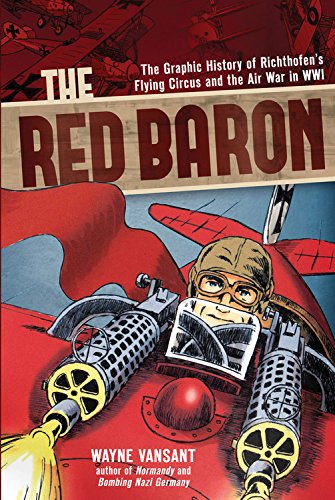

It also educates. He begins with a discussion of women in combat through the ages, the role of aviation, the imagery behind the concept of “the knights of the air” and “aces,” and how aces were counted in World Wars I and II. Theories of state and culture are introduced in order to establish the “mood” of the era into which Lily was born. It isn’t until chapter 6 that the focus turns to aviation and, specifically, aviators, male and female. Long-distance record breaker Marina Raskova’s founding of three all-female aviation regiments, flight training, and then combat service make up the bulk of the book. There are many quotes from contemporary sources and excerpts of previously published material. Inevitably there are also conjecture, assumptions and, so as to stoke tension and create relatability, imagined inner dialogue and staged conversations. The book is absolutely worth reading, just realize it’s not the last or only word.

A stand-alone 8-page section of b/w photos and maps is bound into the center of the book. Appended are a list of acronyms and a long list of materials Yenne consulted; fairly detailed Index.

It is positively uncanny that the year this book was published should be a banner year for Litvyak material. After a hiatus of 25 years, Scottish playwright Peter Arnott’s acclaimed stage play “White Rose” that debuted at the 1985 Edinburgh Festival was performed at the Tron Theatre in Glasgow Feb. 26–March 2, 2013.

Copyright 2024, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter