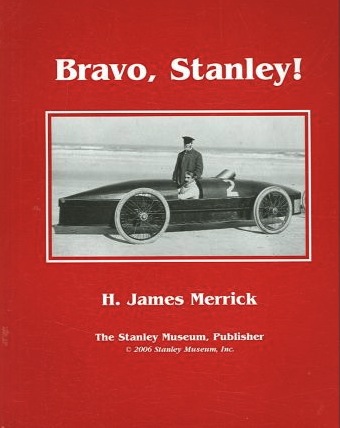

Bravo, Stanley!

The Racing History of Stanley And the 1906 Stanley Land Speed Record

Imagine yourself driving down a clean, flat beach at 150 mph in an upside-down canoe. It’s 1907. You don’t have a steering wheel, you have a tiller. Seat belts are not yet in vogue. You hit a dip in the sand and you’re suddenly airborne. The tiller steering can’t keep up and you hit the edge of the breaking surf. The canoe disintegrates around you and the 30-inch diameter steam boiler, running at 700 degrees Farenheit and 1,400 psi, positioned directly behind you, is ripped away, along with the rear axle and the 206-cubic inch double-acting steam engine geared directly to it. You roll over perhaps a dozen times in the surf, yet miraculously live through it.

If that concept of blatant daring-do appeals to you, then this book will, too. It tells the story of the Stanley twin brothers and their purpose-built steam car that set the world land speed record at 127.66 mph in 1906. Back for more in 1907, their creation crashed at high speed and narrowly missed killing the driver, Fred Marriott. After the crash, the Stanleys, builders of the famous Stanley steam car, reassessed the risk of death surrounding their project. They dropped their world record ambitions, choosing instead to concentrate on running their prosperous car business, leaving the glory of ever-higher land speed records to the “hydrocarbon“ crowd.

Written by Stanley Museum archivist H. James Merrick with financial underwriting provided by the Randall Family, the book opens with newspaper accounts leading up to the 1906 race, interspersed with diary notations by Augusta Stanley, wife of one of the brothers. From there we get a little history of the early beach racing at Ormond, Florida, just north of Daytona. A quick history of the steam car-building Stanley twins—F.E. and F.O.—brings the reader up to speed as the book then concentrates on race day 1906 and 1907, and what happened.

The book presents itself well enough, but my copy had three pages (104, 105, and 108) that didn’t get fully printed upon, leaving the reader to bridge the narrative gap as best s/he can. A few typos appear here and there, but nothing harmful. My main criticism would be directed at the size of the photos—they’re frequently smaller than can be easily seen, yet contain temptingly interesting things to look at—old race cars and their drivers and crews, for instance. The detail in some of those old wet and dry plate photos is tremendous and deserves to be enlarged. Of course, increasing the photo size would make the book longer and more expensive to buy, so a trade-off must be made, I suppose.

I bought the book to help me analyze and satisfy my curiosity about how the racecar was built. The suspension and drivetrain are completely unique and unlike any other car I’ve seen. Although satisfied with what I read, I wish a cutaway drawing of the racecar had been included. No attempt was made to show the reader the mechanics of what is being described beyond a few small pictures showing an earlier iteration of the design. The too-small photos of the wreck show the tangled remains of the drivetrain, which gives some hints at how it was constructed, but nothing like the information that even a simple cutaway drawing could provide. As a suspension components designer, I was both horrified and intrigued at what I could make out. It looks like the wooden frame, suspension, and wheelbase were built light and intended to be flexible. No shock absorbers in sight, and the tiller steering mechanism not shown. Undampened long wooden “perch rod” poles connected the front and rear axle assemblies, holding them in rough alignment. The long unsupported poles undoubtedly affected the wheelbase and steering as they independently flexed up and down at speed, randomly shortening and lengthening the wheelbase from side to side. To complicate matters, the front of the car had so much lift that it became airborne from time to time at 100 to 150 mph. When asked many years later why he had been selected to drive the car, Fred Marriott said, “Oh, I dunno, I probably may have had more balls than any o’ the others.”

The book begins with Acknowledgements, then a Dedication, Preface, Foreword and Introduction in quick succession. Chapters 1 through 11 then take us in chronological order from 1905’s “An Ideal Race Course” through to 1907’s “Black Friday” describing the crash. A Bibliography, List of Illustrations, and the Index finish things off.

All in all, an interesting book, but not a great one, falling into the category of certainly better than no book at all, but nowhere as insightful as it could have been. An engineer’s eye needs to be applied to the available data so those unfamiliar with steam power can get a grip on how the land speed car was built and operated. Incredibly powerful and fast for its day, specifics on the construction of the 1,600-pound steam-powered vehicle is left visually vague and unclarified, leaving this reader hungry for more construction details.

Also available autographed when ordered directly from the Stanley Museum.

Copyright 2013, Bill Ingalls (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter