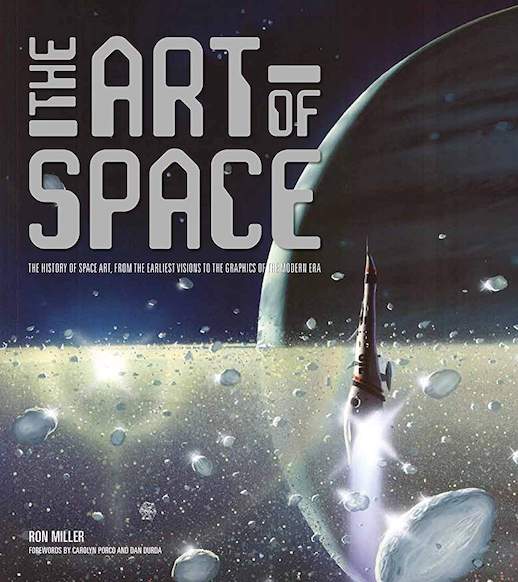

The Art of Space

The History of Space Art, from the Earliest Visions to the Graphics of the Modern Era

by Ron Miller

by Ron Miller

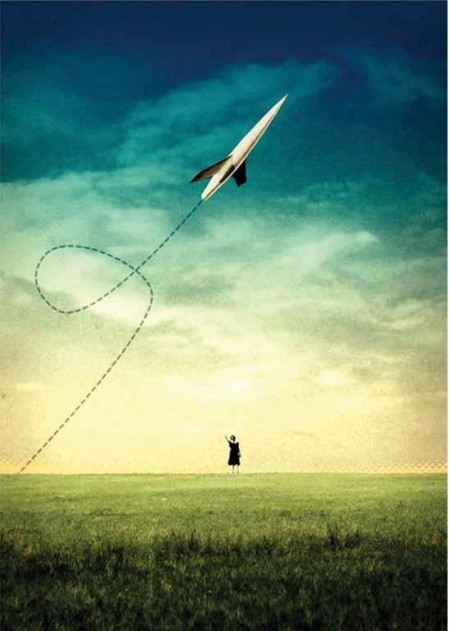

I was excited when Speedreaders suggested I review The Art of Space. I was already aware of the impact of art in general on industrial design throughout history, and looked forward, for my own amusement, to seeing if the “space” art created over the last 180 years had predicted and influenced our current space-age reality.

My expectations were fulfilled when I flipped open the large-format hardcover to see the works of 58 different artists and sources beginning with Paul Fouché (1884), George Roux (1887), and Théophile Moreux (1890s). From woodcuts to today’s photo-realistic digital masterpieces, the imaginations of the artists, tempered with varying degrees of scientific knowledge, are on display. What the old-time artists expected to find is just as interesting as what today’s artists expect to find, based off the latest available information. A thread of logical deduction connects all the art, no matter the age of its origin or current scientific validity.

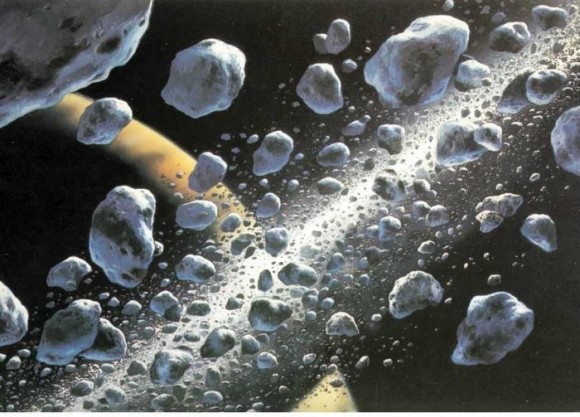

There are 86 black-and-white drawings that illustrate, among other things, early newspaper stories and books about the planets and what their inhabitants might look like. Two-hundred and sixty-five color drawings and paintings dominate the book and display everything from colorful science fiction pulp magazine covers from the 1930s, to an incredibly beautiful and scientifically sound cloud structure, painted by the author, showing what the upper atmosphere of a storm-tossed, lightning-filled gas planet orbiting close to its star might look like. This particular full-color illustration covers both pages of the book, making for an image roughly 20” wide and 10” tall. In total, there are 14 such “double-truck” images scattered throughout, all of them interesting.

There are 86 black-and-white drawings that illustrate, among other things, early newspaper stories and books about the planets and what their inhabitants might look like. Two-hundred and sixty-five color drawings and paintings dominate the book and display everything from colorful science fiction pulp magazine covers from the 1930s, to an incredibly beautiful and scientifically sound cloud structure, painted by the author, showing what the upper atmosphere of a storm-tossed, lightning-filled gas planet orbiting close to its star might look like. This particular full-color illustration covers both pages of the book, making for an image roughly 20” wide and 10” tall. In total, there are 14 such “double-truck” images scattered throughout, all of them interesting.

The book starts out with two Forewords, one written by Carolyn Porco (Cassini Imaging Team Leader and Director of CICLOPS) and Dan Durda (Southwest Research Institute). Both contributors point out the role that art plays today in making “visual—even understandable—what can’t [yet] directly be observed.”

A quick history of space-related art fills the reader in on the Past, Present & Future, then five sections transport us to Planets & Moons, Stars & Galaxies, Spaceships & Space Stations, Space Colonies & Cities, and then . . . Aliens, both beautiful and sinister. Within each section the visions of the various artists are displayed, with exceptional individuals highlighted with a brief biography explaining the how and why of their work. An Index leads into a list of Image Credits, then Further Resources & Acknowledgements, with Contributor Bios ending the book.

Several artists and their paintings are featured. In particular, everyone’s hero, Chesley Bonestell (1888–1986), who created influential pictorial representations for both Willy Ley and Wernher von Braun in the 1950s to help them promote the concept of space flight to the American public. Bonestell also supplied the artistic backdrops for the films Destination Moon, When Worlds Collide, and the famous 1953 version of War of the Worlds, a film still chillingly able to suspend the belief of the viewer due to its science-based artistic creations. In addition to author Ron Miller, Lynette Cook gets to display her talent with 14 works; among them, Floaters is one of my favorites. Jim Burns, Wayne Barlowe, Don Davis, Pat Rawlings, and many other artists included in the book deserve to be mentioned here as well.

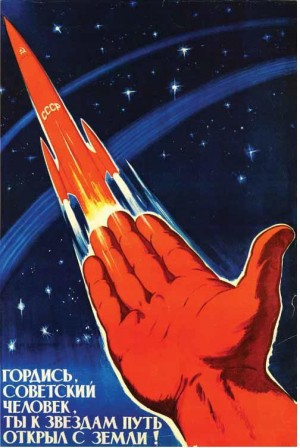

This book is a historic sampler of space art up to the present day, and, for me at least, it does reflect the impact of art on the shape of reality. The artistic renderings that Russian artists created prior to Russian engineers actually designing their Sputniks were obviously influential on the overall shape of their early efforts. There is a reason Yuri Gagarin’s softly bulbous space capsule looked different from the geometrically crisp American Mercury capsule, which performed the same function. Just as you can tell a machine is old by observing its design characteristics (i.e., lots of unnecessary scroll work and metal wasted on non-functional artistic embellishment), you can tell early Russian design from American due to the artistic influences behind each culture. These influences help shape the conceptual thinking of those who put pencil to paper. The purpose may be pure science, but the shape reflects a subconscious notion of what the space capsule should look like when complete. The idea that form follows function will universally, generically lead to identical designs only goes so far. The details are always in the eye of the beholder, and space art definitely plays a role.

This book is a historic sampler of space art up to the present day, and, for me at least, it does reflect the impact of art on the shape of reality. The artistic renderings that Russian artists created prior to Russian engineers actually designing their Sputniks were obviously influential on the overall shape of their early efforts. There is a reason Yuri Gagarin’s softly bulbous space capsule looked different from the geometrically crisp American Mercury capsule, which performed the same function. Just as you can tell a machine is old by observing its design characteristics (i.e., lots of unnecessary scroll work and metal wasted on non-functional artistic embellishment), you can tell early Russian design from American due to the artistic influences behind each culture. These influences help shape the conceptual thinking of those who put pencil to paper. The purpose may be pure science, but the shape reflects a subconscious notion of what the space capsule should look like when complete. The idea that form follows function will universally, generically lead to identical designs only goes so far. The details are always in the eye of the beholder, and space art definitely plays a role.

The author of the book, Ron Miller, is an author and freelance illustrator whose résumé includes being the art director for the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum’s Albert Einstein Planetarium. His art has graced dozens of book jackets, book interiors, and scientific magazines. He also has over 50 titles to his credit.

Dan Durda helped bring this book together, and contributed several pictures as well. In addition to being an artist, Durda is a professional astronomer and planetary scientist. He has authored 70-plus scientific papers and many articles for books and magazines. He has an asteroid, 6141 Durda, named after him!

Also contributing to this book’s success is Carolyn Porco, who started out in the 1980s as an imaging scientist on the Voyager mission, and now leads the Cassini imaging team. She acted as the character consultant for the 1997 sci-fi movie Contact, and advised on planetary imagery for the 2009 Star Trek movie.

Everyone involved in producing this book is an artistic and scientific professional, and the illustration selections reflect that knowledge in a thoroughly engaging way.

If you’re curious about the development of space art over time, or what good examples of space art look like, then this book is worth purchasing.

Copyright 2014, Bill Ingalls (SpeedReaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter