Dead Man’s Curve

by Jan Berry, Roger Christian, Artie Kornfeld, Brian Wilson

by Jan Berry, Roger Christian, Artie Kornfeld, Brian Wilson

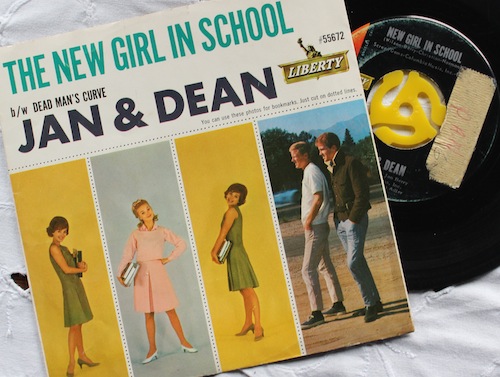

Recorded by Jan & Dean

“Future generations choose and select, apply their own criteria, and decide which works retain the power to communicate their mysterious energy.”

— Calvin Tomkins

If you are under 45 years of age, we can hear you yawning from all the way over here. Don’t they realize that Hip-Hop and Rap have been around for at least a quarter century? Why would anyone bother with a 1964 car song, a teenage tragedy, recorded and released by a second-rate duo, that was on the charts for not much more than a blink of the eye? Oh, and for those over 55 years of age and still invested in this music, we can hear the grumbling already: “Second-rate duo my foot! Kaff! Kaff! Jan & Dean are among the very best . . .” Of course—but we are not talking Dylan, Beatles, Stones and The Beach Boys now are we? Well, we are, at least tangentially. Brian Wilson, for many the Beach Boy, is one of four co-writers of DMC, along with Jan Berry, the Jan of Jan & Dean; Artie Kornfeld, later creator and promoter of Woodstock; and Roger Christian, an L.A. deejay, a friend of Wilson’s, a lyricist who supplied much of the hot rod jargon in The Beach Boys early repertoire .

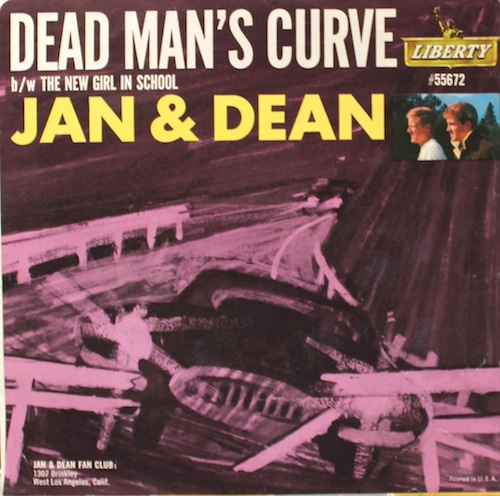

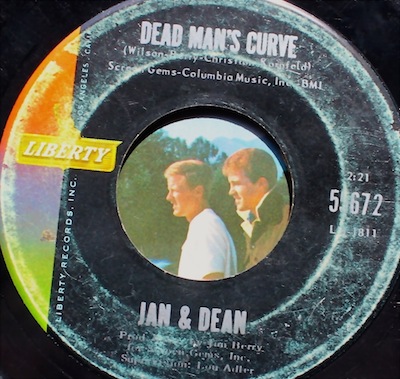

One reason for the attention is because of Brian Wilson’s involvement. He truly is one of the masters of the classic rock era and, more important, he sang backup on the first recording of the song. Another reason is that the song describes a real place—well, sort of—with a history worthy of some consideration. And, still another, is that there are two Jan & Dean versions of the song, three if you count a remix of version two for the 45 RPM release (some strings, more horns, and crash sounds added), four if you count the instrumental-sing-along, ala The Beach Boys Stack-O-Tracks, that shows up on the 1996 two-CD set All The Hits From Surf City to Drag City. At least one live version exists. But the best reason of all is that in all of its permutations, it is just one very ill pop artifact.

One reason for the attention is because of Brian Wilson’s involvement. He truly is one of the masters of the classic rock era and, more important, he sang backup on the first recording of the song. Another reason is that the song describes a real place—well, sort of—with a history worthy of some consideration. And, still another, is that there are two Jan & Dean versions of the song, three if you count a remix of version two for the 45 RPM release (some strings, more horns, and crash sounds added), four if you count the instrumental-sing-along, ala The Beach Boys Stack-O-Tracks, that shows up on the 1996 two-CD set All The Hits From Surf City to Drag City. At least one live version exists. But the best reason of all is that in all of its permutations, it is just one very ill pop artifact.

Again for the under-45 crowd, the Gen Xers, to pay such attention to less than a handful of remixes must seem antediluvian—Gen Xers live in an audio universe of remixes of remixes, a world where there is no concept of a B-side of an LP being a distinct listening entity, where the knowledge of a 45 RPM 7-inch disc has become hazy and certainly irrelevant, where The Beach Boys seem quaint and Jan & Dean seem, well, just plain weird. But back in the day, remixed variants of recordings were infrequent, far between. For the Baby-Boomers, discovering that there are two 45 RPM versions of The Beatles Penny Lane available, one with a trumpet ending, one without, is a big deal. Neurotic collectors know of many more examples of various alternate mixes from various artists, but, generally speaking, remixes from the Classic Rock era are rare when compared to the virtually limitless remix options available today: Download your favorite tune, add your best beats, slow it down, speed it up, add some electronic swirls or audio splashes: viola, you have your very own mix, one of hundreds, if not thousands. Not like the old days at all. Would it be too unhip to drop the phrase du jour: A Paradigm Shift?

When we began looking into DMC’s history, we felt confident that to pin down the three main versions would be straightforward, but as music went from vinyl to CD to Amazon downloads, confusion set in. This has to do with variations of the recording times listed. The 45 RPM version of version two is listed in Brad Elliot’s Surf’s Up/The Beach Boys On Record 1961–1981 as 2:28. On our copy of the DMC disc, it reads 2:21, and one of the downloads adds an additional ten seconds. Elliot lists version one as first appearing on the LP Drag City timed at 3:01 but the downloaded version one appears at 2:49. More confusion arises when we know that the time listed on a disc is not necessarily the actual time of the recording. (Did Elliot accept the disc labels or did he personally time each of the 350 recordings that he catalogs?) The most famous instance of such time manipulation is from back in 1964 when Phil Spector, in order to assure radio play, labeled the Righteous Brothers You Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’ at 3:05 rather than the true playing time of 3:45. Believe us, we tried hard to resolve this DMC quandary with our turntables, CD players, stopwatches, computers, ears and patience, but, frankly, our patience eroded as the process wore on and so we did the best we could. Those with a numismatic bent may find this unacceptable, even contrary to the exacting standards of Speedreaders, and may even argue that there are obviously more than four variations of DMC. But a line must be drawn somewhere, and, at day’s end, exactitude should give way to sanity.

The next question on the table, and a fair one at that, is whether or not DMC, the song itself, is worthy of scrutiny. For those having any sympathy at all with rock-’n’-roll and especially those who hold a fondness for the surf/car subgenre, the answer is an unqualified “Yes.” For those who enjoy rock-’n’-roll, Surf/Car songs, and teenage tragedies, the answer is “Yes!” Car songs reach far back into rock-’n’-roll’s history; more than one historian proposes Jackie Brenston’s 1951 Rocket 88 as the very first rock-’n’-roll song. Then there are The Beach Boys—409, Shut Down, Car Crazy Cutie. And, ah, the Teenage Tragedy subgenre—a world of tears, shattered hearts, wrecked dreams, twisted metal, broken bodies and death! A handful of classics keep the teardrops falling, even up until today. Black Denim Trousers, The Cheers, 1955: Freight train smashes into motorcycle, The Terror of Highway 101 presumably dies (there is some ambiguity here) and Mary Lou grieves. This song was covered, from English to French, L’homme à la Moto, by Edith Piaf. Teen Angel, Mark Dinning, 1959: Girl goes back to retrieve boy’s class ring when car is stuck on railroad tracks. Train comes, girl dies. Tell Laura I Love Her, Ray Peterson, 1960: Tommy enters stock car race to raise money to buy a wedding ring for Laura; Tommy crashes, burns and dies. Last Kiss, Wayne Cochran, 1961 (Later by J. Frank Wilson and the Cavaliers, 1964, and later still, Pearl Jam, 1999): Rainy night. Boy swerves to avoid head-on collision, car crashes, boy regains consciousness, kisses girl one last kiss. Girl dies.

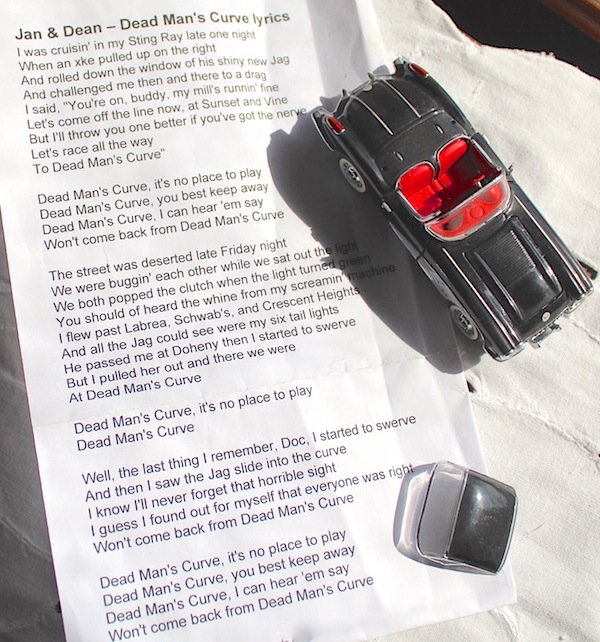

And, in 1964, we have Dead Man’s Curve, Jan & Dean: Late one Friday night in Los Angeles, our unnamed narrator was out cruising in his Corvette Stingray and was challenged by a brand new Jaguar XKE. The challenge was accepted, but the Stingray threw out a counter-challenge: “Let’s race all the way to Dead Man’s Curve.” “The strip [version one]/street [version two] was deserted” that time of night, and they agreed to begin the race at Sunset and Vine. They both “popped the clutch when the light turned green,” and the race was on. The Stingray pulled ahead: “All the Jag could see were my frenched [version one]/six [version two] taillights.” Notice that the identity of the driver becomes the car itself.

And, in 1964, we have Dead Man’s Curve, Jan & Dean: Late one Friday night in Los Angeles, our unnamed narrator was out cruising in his Corvette Stingray and was challenged by a brand new Jaguar XKE. The challenge was accepted, but the Stingray threw out a counter-challenge: “Let’s race all the way to Dead Man’s Curve.” “The strip [version one]/street [version two] was deserted” that time of night, and they agreed to begin the race at Sunset and Vine. They both “popped the clutch when the light turned green,” and the race was on. The Stingray pulled ahead: “All the Jag could see were my frenched [version one]/six [version two] taillights.” Notice that the identity of the driver becomes the car itself.

At first the Stingray grabbed and kept the lead but was eventually overtaken. Then, and here comes the heavy drama, the Stingray “started to swerve” and the Jaguar slid “into the curve.” It is here in version two we hear brakes squealing and the metal-wrenching, blistering sound of the XKE crashing to its doom. Cue up the harp, and, spoken not sung, the narrator tells his story to the attending physician. It is debatable whether the narrator is telling the story as he is dying or if he avoided crashing the Stingray, survived, and is reflecting on the horror of the situation. The ambiguity presents itself at the end of verse two: “He passed me at Doheny then I started to swerve, but I pulled her out and there I was [version one]/there we were [version two] at Dead Man’s Curve.” He “pulls her out.” That’s pretty much it, but DMC soars with a great hook, a sing-along chorus, an adept arrangement, strong production values, and proficient harmonizing.

We prefer the vocals on version one as there is no way that Jan and/or Dean can match the purity of Wilson’s voice,* as he had cut his musical teeth on the tight harmonies of The Four Freshmen. Dan & Jean had been around since 1958 waxing cute pop-love ballads, Baby Talk (1958) and Heart and Soul (1961) being the best known. Their voices are competent, but they never quite escape that nails-on-slate timbre that has made many a serious music lover cringe. They became caught up in the California Sound of Surfing and Cars, from both an aesthetic and commercial perspective, and they befriended Wilson, who, with his fellow Beach Boys, were, in the early 1960s, the crowned leaders of that genre. In 1963, Wilson collaborated with Berry and Surf City was born, a number one hit for Jan & Dean. It’s ascendency—and DMC’s continuing popularity—was undoubtedly helped along by the instrumental backup of The Wrecking Crew, a contingent of LA sidemen, including Hal Blaine, Leon Russell and Glen Campbell, who had contributed so much power to Spector’s Wall of Sound and later to The Beach Boys Pet Sounds. Surf City was soon followed by Drag City, written by Berry, Wilson and Christian, and found its way into the national Top Ten charts. DMC was the next big hit, and Jan & Dean’s reputation was firmly established, remaining rock-solid, at least to the over-55 set, to the present day.

There is an interesting marginal note in all of this that concerns Brian’s father Murry Wilson. The elder Wilson, although initially a strong factor in the success of his boys, was known neither for his kindness nor his wisdom. In 1969 he sold The Beach Boy’s Sea of Tunes catalog for around $72,000 (accounts vary), and broke Brian’s heart. Brian eventually regained control of his songs; it was found that Murry, among his other shenanigans, had forged Brian’s signature. When Murray got wind that Brian was writing tunes for “rivals,” he scolded and fumed. His exact reaction to finding Brian actually singing backup on the first recording of DMC is probably unknown, but we can assume that it was not charitable. We should, however, return to our thesis and wrap it up, offering a brief look into the actuality of Dead Man’s Curve—the place, not the song.

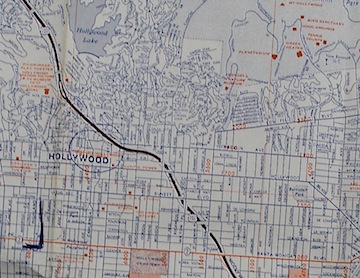

Although the Dead Man’s Curve is real and the cross streets mentioned in the song, La Brea Ave., Crescent Heights and Doheny, are also real, they do not intersect Sunset Boulevard as DMC would have us believe. Searching the internet for verification of this yields confusing and conflicting results. What appears to be accurate is the account given by Bob Shannon and John Javna from their 1986 book Behind The Hits: “Rather than setting their fictional drag race at the site of the actual Dead Man’s Curve, the lyrics place it more to the east—from Hollywood and Beverly Hills and bordered by Doheny Bay, the names of locations more familiar to audiences outside of southern California, such as the famous intersection of Hollywood and Vine, home to the distinctive Capitol Records tower, and Schwab’s drug store. (A race running the route described in the song, from Hollywood and Vine to Sunset and Doheny, would have covered 4.5 miles; extended to the real ‘dead man’s curve’ near UCLA, it would have been a drag of 8.7 miles.).” The very real danger of Dead Man’s Curve resulted in several highway accidents, some of them fatal. Mel Blanc, the original voice of Porky Pig, Foghorn Leghorn, Barney Rubble, Cosmos Spacely and others, crashed there. He eventually sued the city, and after this the roadway was re-engineered to make it safer.

Although the Dead Man’s Curve is real and the cross streets mentioned in the song, La Brea Ave., Crescent Heights and Doheny, are also real, they do not intersect Sunset Boulevard as DMC would have us believe. Searching the internet for verification of this yields confusing and conflicting results. What appears to be accurate is the account given by Bob Shannon and John Javna from their 1986 book Behind The Hits: “Rather than setting their fictional drag race at the site of the actual Dead Man’s Curve, the lyrics place it more to the east—from Hollywood and Beverly Hills and bordered by Doheny Bay, the names of locations more familiar to audiences outside of southern California, such as the famous intersection of Hollywood and Vine, home to the distinctive Capitol Records tower, and Schwab’s drug store. (A race running the route described in the song, from Hollywood and Vine to Sunset and Doheny, would have covered 4.5 miles; extended to the real ‘dead man’s curve’ near UCLA, it would have been a drag of 8.7 miles.).” The very real danger of Dead Man’s Curve resulted in several highway accidents, some of them fatal. Mel Blanc, the original voice of Porky Pig, Foghorn Leghorn, Barney Rubble, Cosmos Spacely and others, crashed there. He eventually sued the city, and after this the roadway was re-engineered to make it safer.

And, finally, we must mention that DMC was most likely inspired by the fact that Berry and Torrence actually owned a Corvette Stingray and an XKE Jaguar respectively, and they were known well to race these “screamin’ machine[s].” And in one of those eerie rock-‘n’-roll coincidences, Jan Berry suffered severe brain damage—he was lucky to have survived at all—when, on April 12, 1966, at 90 mph, he crashed his Stingray into a parked truck close to the location fictionalized in the song. When writing DMC, Christian, suggesting a far less dire dénouement, wanted the race merely to end in a tie, but Berry insisted that the song end fatally. DMC was used to title the Jan & Dean 1978 TV Bi-op. The song has been covered by other artists over the years, The Belljars, Blink-182 and Nash the Stash among them. In 1973 it appeared on The Carpenters LP Now & Then, perhaps the most peculiar detail of the Dead Man’s Curve legacy. So go online, download all the versions you can find, sit back in your favorite lounger, listen to them all for a few days running—to ponder there all of the possibilities of this essential Golden Old One.

And, finally, we must mention that DMC was most likely inspired by the fact that Berry and Torrence actually owned a Corvette Stingray and an XKE Jaguar respectively, and they were known well to race these “screamin’ machine[s].” And in one of those eerie rock-‘n’-roll coincidences, Jan Berry suffered severe brain damage—he was lucky to have survived at all—when, on April 12, 1966, at 90 mph, he crashed his Stingray into a parked truck close to the location fictionalized in the song. When writing DMC, Christian, suggesting a far less dire dénouement, wanted the race merely to end in a tie, but Berry insisted that the song end fatally. DMC was used to title the Jan & Dean 1978 TV Bi-op. The song has been covered by other artists over the years, The Belljars, Blink-182 and Nash the Stash among them. In 1973 it appeared on The Carpenters LP Now & Then, perhaps the most peculiar detail of the Dead Man’s Curve legacy. So go online, download all the versions you can find, sit back in your favorite lounger, listen to them all for a few days running—to ponder there all of the possibilities of this essential Golden Old One.

- * Wilson’s voice has been in decline for a long time now. It would be lovely if some genie in some lamp somewhere could restore it back to its 1960s clarity and innocence.

- PS: Pop Quiz: Which of The Beach Boys co-sang lead with Brian Wilson on their hit single Barbara Ann?

- [Answer: None of them; Dean Torrence did.]

Copyright 2015, Bill Wolf (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

Cool article. Needed to clarify, though, that Mel Blanc did not die in his 1961 accident on Dead Man’s Curve. After waking from a two week coma, he filed a lawsuit against the city. The embankment of the curve was altered after that to make it less dangerous. Blanc didn’t pass away until 1989. His son went on to voice many of his characters after that.

Hello Dominick

Thanks so much for taking the initiative to write us. The review writer concurs with your comment and has rephrased that paragraph accordingly (which we then point out at the end of your comment).