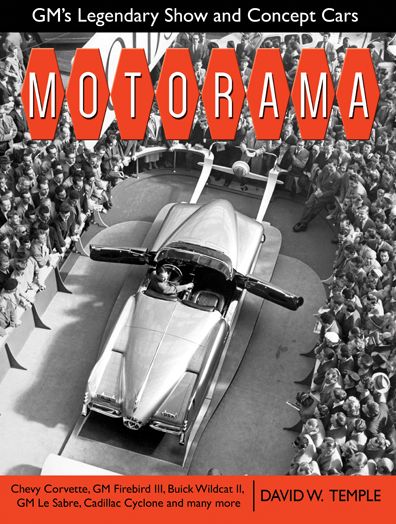

Mid-Atlantic American Sports Car Races 1953–1962

“It would be incorrect to assume that these race venues only put on mundane events. A surprising amount of controversy, political infighting and power struggles went on between the different parties, more concerned in looking after themselves than looking at the overall picture. Occasionally even the race sponsors needed to be kept in check, for while they knew how to raise money, their people skills were sometimes lacking.”

Nothing against the Miata—Spec Miata is the largest and most popular class within NASA these days (that other NASA, the National Auto Sport Association)—but this type of club racing is a far cry from the wild and wooly days of yore.

If you’re from Kentucky or North Carolina, this book has you covered too even if, strictly speaking, Mid-Atlantic means Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, and District of Columbia. While branching out west to include Kentucky’s one major circuit, Louisville, may be a bit of a stretch, looking south to North Carolina’s Winston-Salem and Raleigh tracks is an obvious choice because they were so fully integrated into the racing fraternity’s comings and goings.

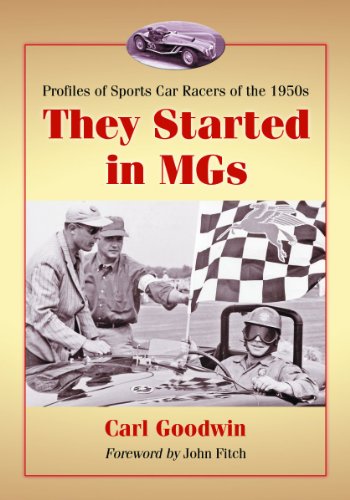

For people interested in the beginnings of sports car racing in the US, recent years have yielded—after years and decades of neglect—a rich crop of authoritative, definitive books that introduce into the record people, places, cars and results, consolidating what was scattered or obscure and saving it from perishing one day altogether. Neither the writers nor those they write about are getting any younger and it is an interesting phenomenon that enough willing and able scribes find themselves at a point in life where their availability coincides with advances in computing power and digitization of records that makes at least some mountains scalable.

For people interested in the beginnings of sports car racing in the US, recent years have yielded—after years and decades of neglect—a rich crop of authoritative, definitive books that introduce into the record people, places, cars and results, consolidating what was scattered or obscure and saving it from perishing one day altogether. Neither the writers nor those they write about are getting any younger and it is an interesting phenomenon that enough willing and able scribes find themselves at a point in life where their availability coincides with advances in computing power and digitization of records that makes at least some mountains scalable.

O’Neil is a Brit but he comes by this quintessential American topic organically, having circled the wagons for years with important books about this crucial decade in which amateur racing morphed into pro racing, with all the attendant upheavals in terms of organization and execution.

Readers new to the subject of regional racing would be well advised to first read O’Neil’s third book, Runways and Racers: Sports Car Races Held on Military Airfields in America 1952–1954 because it goes into more Big Picture detail about how and why the amateur racing grew, in fact why it became a fully organized and now ubiquitous sport at all.

Readers new to the subject of regional racing would be well advised to first read O’Neil’s third book, Runways and Racers: Sports Car Races Held on Military Airfields in America 1952–1954 because it goes into more Big Picture detail about how and why the amateur racing grew, in fact why it became a fully organized and now ubiquitous sport at all.

It is not coincidence that some of the significant examples of this current crop of books come from the same publisher, and that there is a family resemblance to their appearance and approach. Willem Oosthoek’s trilogy Sports Car Racing in the South covers the same era but a different area and while the two authors did not specifically work in tandem they did communicate about the north/south divide, which is naturally occurring demarcation point anyway and not just in geographic terms. That both author’s books look similar is thanks to sharing a designer. A very visible commonality is the graphic treatment of titles, the key difference being that O’Neil follows British convention in the day/month treatment (as well as British spellings throughout).

If the Mid-Atlantic region is not “your” area, realize that its different dynamic and demographic (cf. less of an industrial base and more business- and commerce-oriented; fewer auto dealers and distributors) meant its racing activities developed differently (i.e. slower) than other areas. The oval track/Nascar/SCODA crowd didn’t exactly embrace them furrin cars or the folks that ran them and these political and economic factors clearly play a role.

If the Mid-Atlantic region is not “your” area, realize that its different dynamic and demographic (cf. less of an industrial base and more business- and commerce-oriented; fewer auto dealers and distributors) meant its racing activities developed differently (i.e. slower) than other areas. The oval track/Nascar/SCODA crowd didn’t exactly embrace them furrin cars or the folks that ran them and these political and economic factors clearly play a role.

The book progresses in chronological order, one year per chapter. Early on O’Neil makes the point that the suspicion towards cars that had sponsors or uncommonly well-heeled owners able to hire drivers giving them an unseemly advantage was nothing new, having first been raised already 60 years earlier.

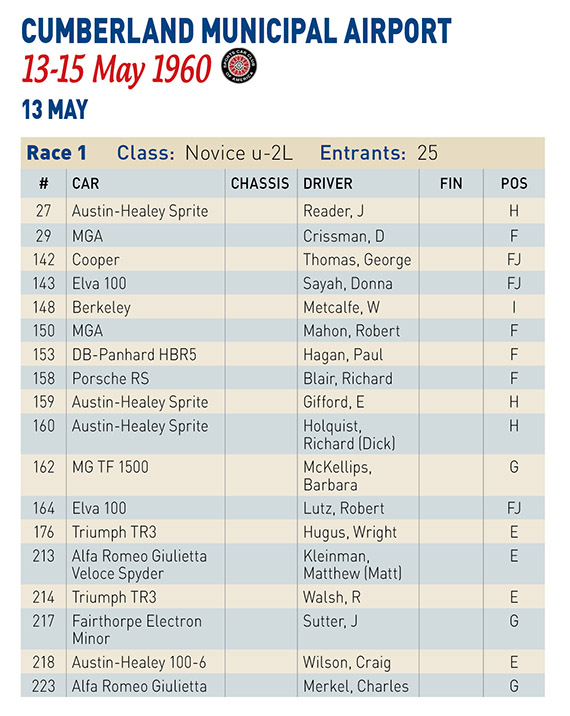

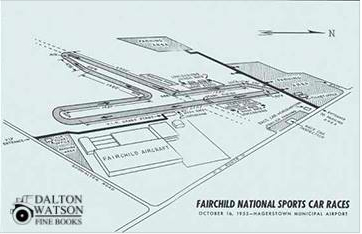

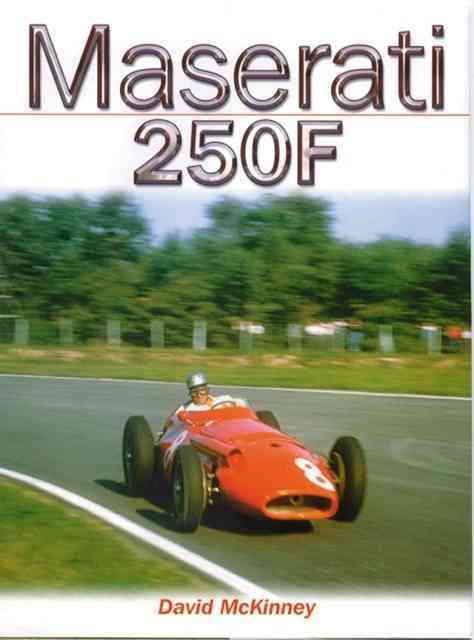

Within each year, an overview of major developments leads into a discussion of specific events at varying levels of detail (read the Introduction to the book to understand O’Neil’s approach to what and how he covers it) and ends with tables of results for those races but on occasion also others that were too minor or too poorly documented to warrant coverage in the main text. A multitude of thoroughly captioned period illustrations, including maps  and race posters, ticket stubs etc. give testament to a distinctly different time, fairly exotic machinery (from the obscure [Siluro-Crosley, Revis, Merlyn] to the unexpected [Karmann Ghia, Simca] to the inevitable [Maserati, Ferrari, Jaguar, Porsche]) and every now and then you’ll recognize a prominent, often international driver that already had done or would go on to great things.

and race posters, ticket stubs etc. give testament to a distinctly different time, fairly exotic machinery (from the obscure [Siluro-Crosley, Revis, Merlyn] to the unexpected [Karmann Ghia, Simca] to the inevitable [Maserati, Ferrari, Jaguar, Porsche]) and every now and then you’ll recognize a prominent, often international driver that already had done or would go on to great things.

In an earlier review we lamented the fact that tables or other data sets utilized acronyms whose meaning is not universally clear; this time there’s a legend. The Indices are impressively deep. In every regard this is a worthy and worthwhile and important book; its run is limited to 600 signed and numbered copies.

O’Neil has already covered the Northeast, Martin Rudow attended to the Pacific Northwest, Mike Martin wrote the definitive USRRC book, Dick Wallen and cohorts have a number of pertinent offerings but quite different in scope and execution—which means the Mid-West is missing. O’Neil has that on his to-do list but first comes a book about sports car racing at Thompson Speedway and Raceway up to 1967.

Copyright 2015, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter