Tom Tjaarda: Master of Proportions

by Gautam Sen

by Gautam Sen

“I had a girlfriend, Susan. Tall, with red hair. Very American looking and attractive, but she left me for Tom Wilton. He was a car designer, and had much success with women, and was forever touring the world. I wanted to be like him, and so I signed up for the industrial design course.”

Susan should have stuck with Tjaarda because Wilton may have had success with women but as a car designer he did not put a dent into the universe. Tjaarda, on the other hand . . . where do you end?

His beginning was auspicious enough: fresh out of school he got himself hired by Carrozzeria Ghia and designed them a complete car, an Italian interpretation of the British Austin-Healey Sprite. But totally different.

How long do you have to live in your adopted country to be considered a native? Tjaarda (1934–2017) lived and worked in Italy for some six decades and still the shorthand for him is “that American in Italian design.” Never mind that Stevens Thompson Tjaarda van Sterkenberg (ignore any other spellings you might find elsewhere), while born in that most American of motor cities, Detroit, was the son of a Dutch designer and would have thus been exposed to at least some European sensibilities already in a pre-cognitive state. (Even though his parents divorced when he was five, Tjaarda remained in touch with his dad, attributing the “decision to design automobiles” to his influence and considers it “inherited.”)

Speaking of a “cognitive state,” is one’s signature a matter of consciously selected styling or does it “just happen”? Whichever, you only have to behold Tjaarda’s signature to see here’s someone who’s not timid about using line and proportion to say something about himself.

Speaking of a “cognitive state,” is one’s signature a matter of consciously selected styling or does it “just happen”? Whichever, you only have to behold Tjaarda’s signature to see here’s someone who’s not timid about using line and proportion to say something about himself.

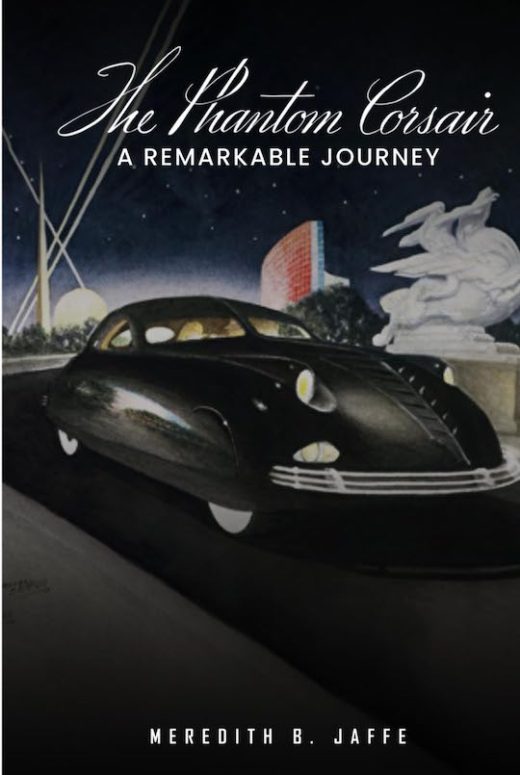

This is one of those grand books, grand in scope and grand in presentation, that make any review feel rather superfluous and also inadequate in capturing the fulness of its many merits. That the author knew the man he writes about is of course one merit; that his several fine books in recent years on design matters have sharpened the acuity of his perception is another; but that he actually walked in his subject’s shoes is an aspect that elevates this book in a very special way: that Gautam Sen, a native of India where he was a pioneer of automotive journalism, moved to France, where he remains to this day, is because once upon a time he was dispatched there to orchestrate the design and development of India’s first sports car, the San Storm. Short-lived and probably quite forgotten today even by Indians, that project and others involved making contact, and actually working with notable car designers on the order of a Gerard Godfroy and Marcello Gandini (the subject of an earlier book)—and Tom Tjaarda, the subject of this book. Ergo, Sen’s understanding of design and manufacturing parameters is not formed by mere book knowledge or abstractions.

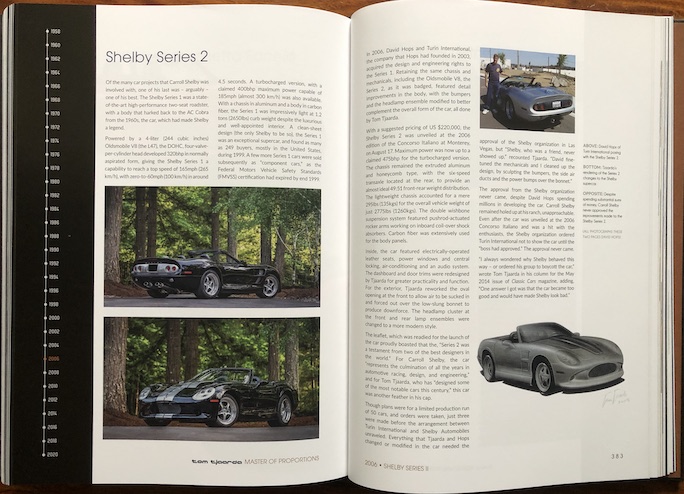

Though commissioned by Shelby Automobiles and announced with much fanfare, this Tjaarda-designed Series 2 never got approved by Carroll Shelby, costing Tjaarda and the fabricator millions. Especially in the early days, Shelby had a checkered reputation for his behavior in business but even at the end his compass was not true. As late as 2014 Tjaarda would write, “One answer I got [about Shelby’s intransigence] was that the car became too good and would have made Shelby look bad.”

Sen—and pretty much everybody—describes the Pantera as “Tom’s most epochal design.” Here Tjaarda with his personal, highly modified car. Note the new bumper/spoiler and wheels. Only two of these Specials exist. Tjaarda sold his, of all places, at a Barrett-Jackson auction.

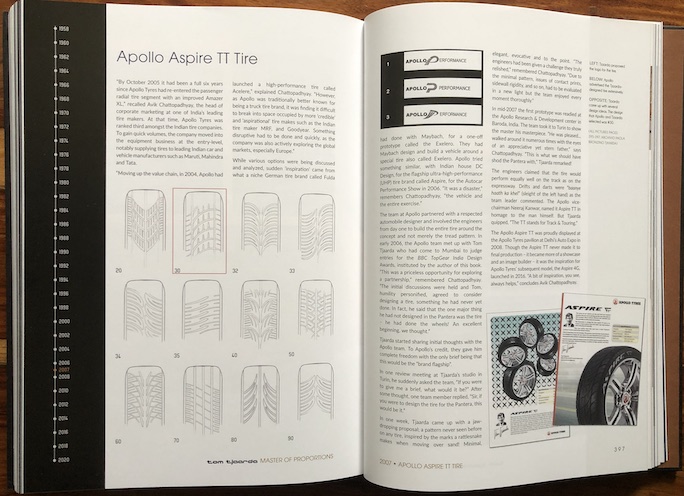

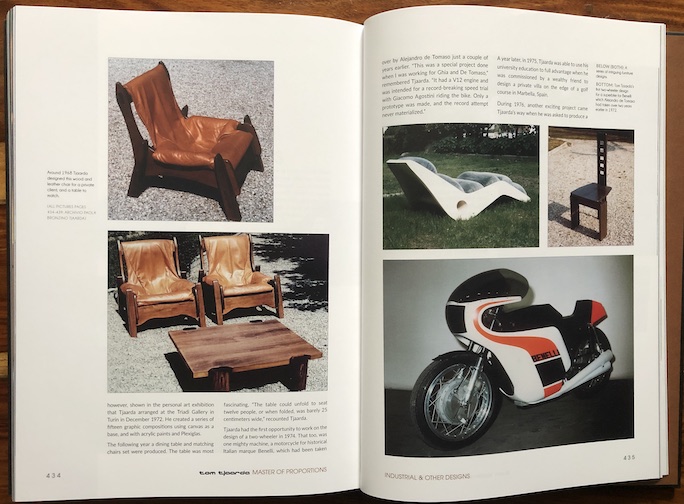

Not all designers design every single thing on a car. Tjaarda did design the wheels of the Pantera—but not the tires, something he always considered a missed opportunity. In 2005/6 he was asked to design a tire, just the tire alone, from the tread pattern (“inspired by a rattlesnake moving over sand”) to the logo.

Sen’s is not the only Tjaarda book in recent years (2011, Tom Tjaarda uno stilista d’oltreoceano by Filippo Disanto and 2019, L’americano. Tom Tjaarda a Torino 1958–2017 by Giosuè Boetto Cohen [bilingual, and cheap!]) but it is by far the most wide-ranging and, being a Dalton Watson book, unmatched in terms of design and bookmaking quality. And while Tjaarda certainly had a relationship with all three writers, it is Sen to whom he entrusted the two aborted autobiographies he himself had once undertaken. The form in which that material is used here presents about the only point of possible ambiguity: Sen quotes Tjaarda often and at length, these passages being enclosed by quotation marks but it is not usually clear which is picked up from the several interview sessions they conducted and which is an old musing of Tjaarda’s from/for his own notes. This would be relevant insofar as thinking (and recall) tends to be affected by the passage of time. For instance, Tjaarda’s own words about his father, written in 1972 at the age of 38 for a magazine, not only are remarkably insightful both about the personality and the oeuvre but also demonstrate full command of car design history particulars.

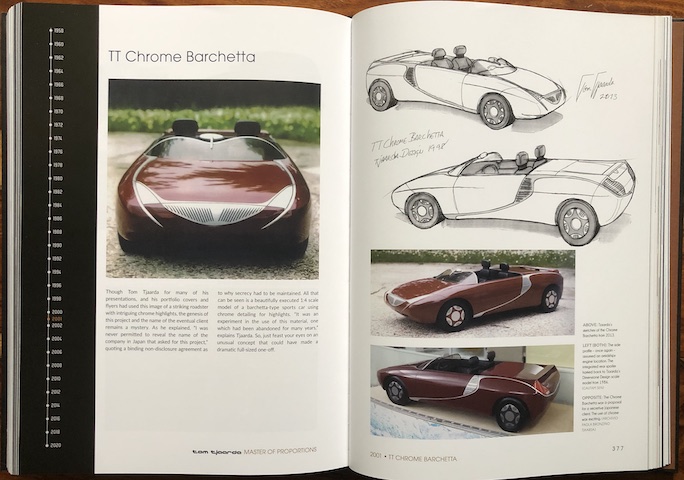

Every time a new design is up for discussion there will be a timeline on the outside margin. As to the TT Chrome shown here, citing an NDA Tjaarda would not say who the Japanese client for this project was. Now that info has gone to the grave with him!

The book is chronological, divided into 8 chapters. It is no small accomplishment that Sen manages to keep Tom Tjaarda the man in front of the reader’s eyes no matter how much the thrust of the story is on technical and professional matters. From childhood to last projects, it’s all here. It is safe to say you’ll never be “done” with his book. If you are pro designer you’ll be tempted to skip over certain parts initially; if you are new to all this, every page will lead you into new rabbit holes.

Sen has woven into the story innumerable commentaries from industry types, and whether the cars (and other projects) are old or new, you’ll find yourself thinking that Robert Cumberford was right when he called Tjaarda—not in this book, maybe because it would be too on the nose—“one of the world’s most accomplished Italian car designers.” His peers pretty much always took note and this book brings Tjaarda to the attention of the public at large, correcting the lament by another influential design resource, Car Design News (a German online news service for the international auto design community) that he is “one of the great unsung heroes of the car design world.”

Appended are examples of scale models of Tjaarda car designs, a Bibliography, and an excellent multi-tiered Index.

The book uses a lot of glossy blacks. Unless you wear gloves or have abnormally dry skin, the pages will be crawling with fingerprint smudges in no time.

Lastly, it will not be lost on readers with an eye for design that this book is smartly designed. Typefaces, to single out just one aspect, are the sort of thing you’re never supposed to think about—if they work. Jodi Ellis Graphics has designed probably most Dalton Watson books and has once again made an inspired font choice (for heads and captions) that not only looks good but has the coolest name: Champagne & Limousines. Never heard of it? That’s probably because it was created by a single mom who thinks up fonts (and other stuff) in her free time and makes them available to bloggers. For Ellis to even have this font on her radar says something about how plugged in she is.

Copyright 2021, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

THANK YOU SO MUCH!! The review is…just too good to be true!

—Gautam Sen