Le Mans 100, A Century at the World’s Greatest Endurance Race

by Glen Smale

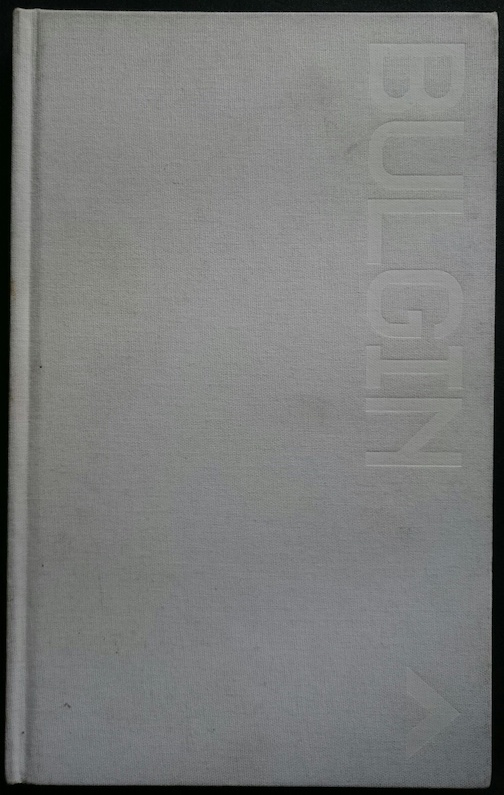

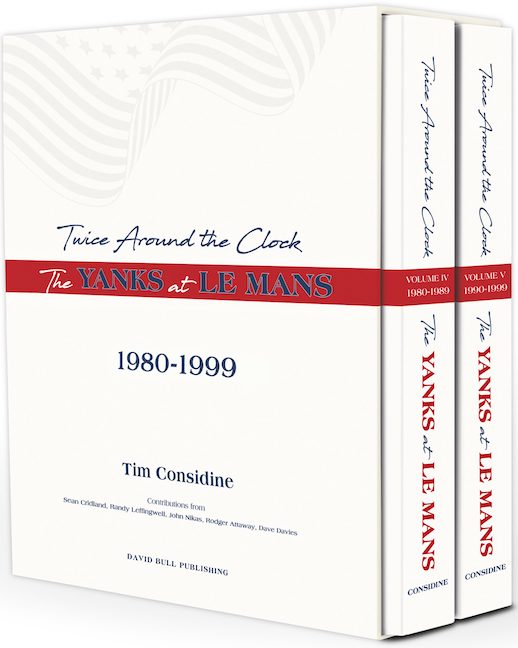

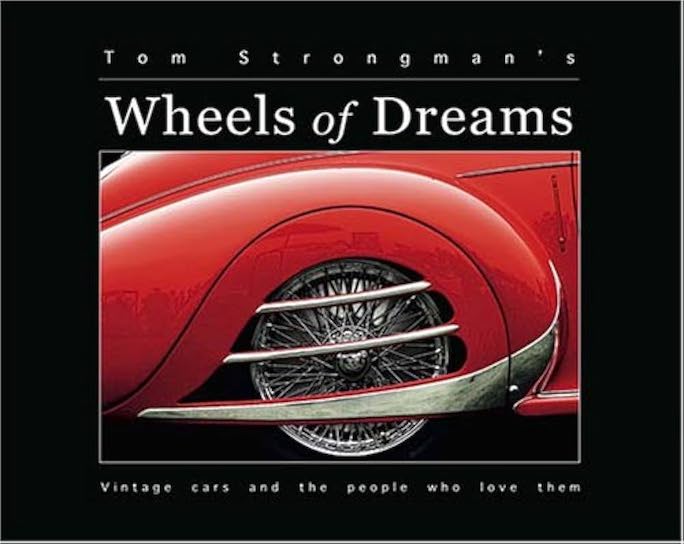

Handsome presentation; on the right the red linen slipcase with embossed track map. Fancy, n’est-ce pas?

“The inaugural Grand Prix d’Endurance was held in 1923 on the Circuit de la Sarthe and was to be contested over a 24-hour period. The event was structured so as to give recognition to production vehicles and to test the reliability and performance of those motor vehicles that could be bought off the showroom floor. Modifications were not permitted, and various stringent regulations were imposed that ensured that each competitor maintained its performance against a predetermined distance allocation throughout the event.”

Well, now you know how it started. Doesn’t sound a whole lot like today’s 24 Heures, does it? This book is sort of a race-by-race highlight reel, handy to have as a quick memory-jogger to keep track of all those changes, at least in broad strokes, and equally handy for a new reader to just hunt and peck.

A hundred years of anything is certainly noteworthy, and big fat anniversaries have a habit of spawning all manner of commemorative publications. Too often they are merely opportunistic fluff but that is not the case here. There are at least three good reasons to single out this book from the several that are even worth knowing about. To wit: the author’s qualifications, the book is officially endorsed by the race organizer, and the winningest Le Mans driver wrote a very lucid Foreword.

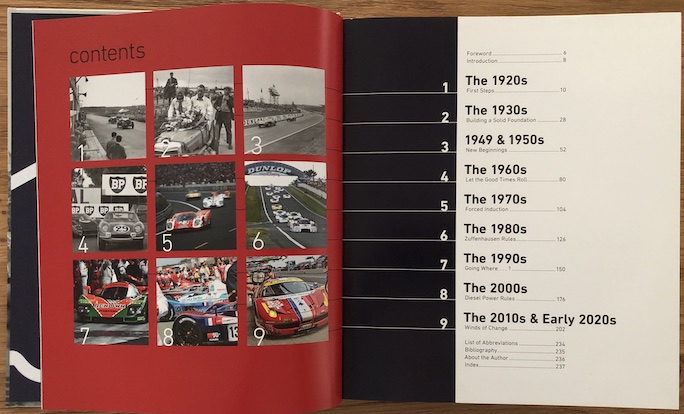

The numbered photos on the left correspond to the chapter numbers on the right. Only looks easy when you see it finished, but imagine starting with a blank page and hoping for inspiration . . . and the whole symmetry of the photos would be ruined if the author had insisted on the “right” number of chapters!

Le Mans 100 is a genuinely fine overview of the first hundred years during which Le Mans was run ninety-one times. That’s 100 calendar years, counting 2023, which is not included in this book as it had already been published. While the book has a listed release date of August it was printed already in June, the same month the race was run. On the one hand one has to applaud author and publisher for wanting to get in front of it, on the other hand you can just imagine the gnashing of teeth over having to leave out the one race that made history in the biggest possible way: one storied marque took the overall win for the first time after almost half a decade, also pole, also fastest lap, and it was a nail-biter to the end (that was Ferrari, in case you live under a rock). Undoubtedly, from here on out, 2023 will feature as the poster child of everything that endurance racing is all about.

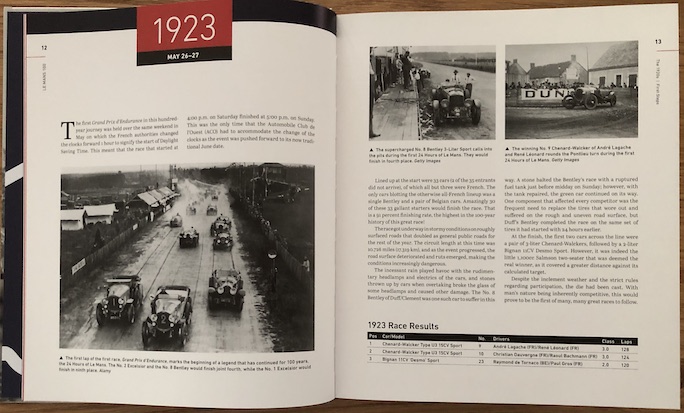

This spread presents the inaugural Grand Prix d’Endurance, held in May the same weekend as the French authorities had designated Daylight Savings Time, meaning the day the race started (Saturday) was an hour “off” in comparison to when it ended on Sunday. All subsequent runnings were therefore pushed back to June! (And occasionally later.) The event rules were enormously complicated and proved impossible to maintain; they were abandoned before the decade was out.

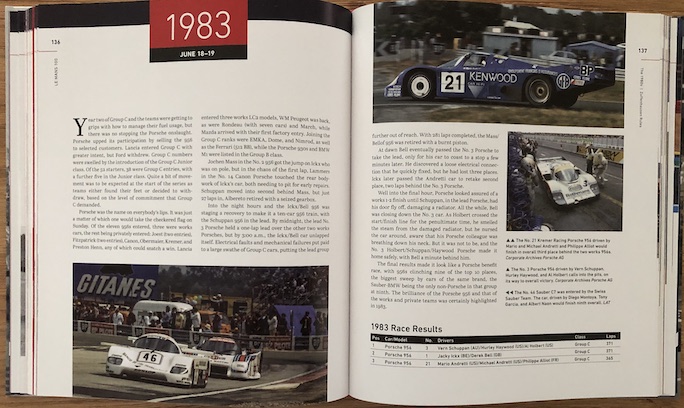

Why were there “only” ninety-one races held? Well, there was that small matter of the second World War during which all racing was suspended. Then in 1936 a labor strike in France. So, for this book, focus on that word overview, for that is all that is possible in 240 pages illustrated with just shy of 300 images. This translates to a mere two pages per race (example below), including a table of the top three finishers for each. The book is divided into decades, each of which introduced also by a page-pair. If this makes you yearn for more look no further than Quentin Spurring’s now 7 volumes strong Le Mans series that starts in 1923 and will be continued (originally published—in collaboration with the Automobile Club de l’Ouest—by Haynes and now continued by their successor, Evro; be prepared to part with around £350 for the current set of seven).

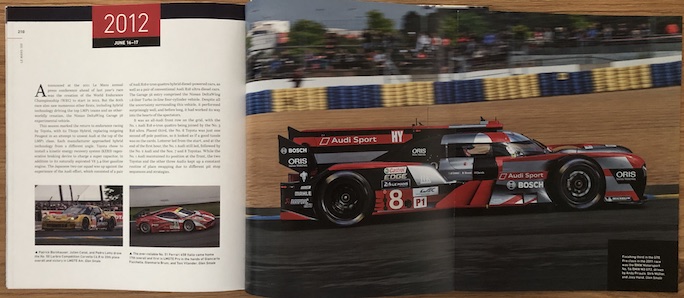

Images from the 60th anniversary year of Le Mans clearly show the evolution of contending cars’ profiles. Porsche dominated that year with eleven 956s entered, three of which accomplished the podium finishes.

Smale wrote a whole book about just the Porsches at Le Mans. Our review ended with words that apply to this one just as much: “As we said at the beginning of the review, Smale writes a book the way he would read it, or, more importantly, use it, which goes far beyond what the casual reader expects of a book.”

That Porsche book was also published by Quarto but had a different designer—something you don’t notice right away. They look similar yet different, and each is a fine example of confident design choices and good layout.

Squeezing the most out of/into a short book takes much more discipline than writing a long one, and veteran photo-journalist-author Glen Smale makes every word count. He’s covered the race as a motorsports reporter 26 times and he’s as much a fixture in the paddock as on the publishing scene. He has been building up his own voluminous archive since turning professional in 1994 and many of the pages here about races after the millennium feature some of his fine photography.

This is one of the two gatefolds. On the back/s are race posters.

Shown on the right, in a Smale photo, is a BMW M3 GT2. You’ll know that M3 model designation as road car but this racer is a far cry from the unmodified production cars for which this race had originally been intended.

Smale’s disciplined overview also means that the human faces and stories cannot be explored in any depth in this book. Both are certainly recognized as part of the mystique and magic of Le Mans in the Foreword penned by Tom Kristensen and by Smale in his Introduction. Two books about TK came out just in 2021/22; there and here he makes the not at all obvious point that it is not the winning—and remember, he’s been on the top spot of the podium more than anyone—but other factors specific to Le Mans that make it “the ultimate challenge” and that “the more it knocks you down, the harder you work throughout the next 12 months to be able to take revenge.” One tidbit that Smale found important enough to say is that the first race, in 1923, had a higher percentage of finishers (30 of 33 starters, ~91%) than any race since; there are multiple storylines wrapped up in that one statement and they are all related to the ultimate raison d’être for endurance racing: to try out new technology and then harden it to trickle down to the ole grocery getter.

One recent publication is worth mentioning because you can still find it easily, the April-May 2023 issue of Road & Track magazine which devoted all its 128 pages to all things Le Mans, including that most catastrophic of motorsports accidents, the 1955 carnage when Pierre Levegh’s Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR flew into a crowd of spectators. That incident has been written up 1001 times but R&T has an eyewitness account from a now 85-year-old Brit who had been given a trip to Le Mans as a surprise 17th birthday gift.

Limited though its depth of coverage, of necessity, is the book will please Le Mans cognoscenti with the fine photography permitting close study of details of those cars shown as all images are published large. Smale’s choice of photos is of course tailored to the intended user of his book; this is another way of saying that a good number of the truly iconic photos have already appeared in print before. For those hunting for more exotic imagery, turn to 24 Hours of Le Mans: 1923–2023 Centenary Edition by J-M Teissedre and T. Villemant (Editions Cercle d’Art, ISBN 978-2702211373, in English and French). It’s more than double the price so the Smale/Quarto book looks mighty attractive.

Hand me that magnifying glass, Watson . . .

Above, we remarked that the event coverage is brief. We also established that Smale knows his stuff. Ergo, the following is not meant to belabor the inescapable reality that a book produced to parameters dictated by economics is apt to fall short of absolute perfection, which is also why we generally take minor irregularities in stride. That said, a reviewer is always walking a fine line between precision and pedantry; our examination of one particular page is meant to deliver the former, not the latter.

We chose page 73 for convenience’s sake because it happens to illustrate within a few paragraphs a sort of chain reaction. Throughout the book, Smale alternates between using the names of drivers vs makes of car in describing race action. Rarely are there two drivers with the same surname but there is definitely more than one model of any one make, so using the more unique qualifier (proper name) would prevent ambiguity, right? So, p. 73, near the end of the 1956 race coverage, refers to driver Paul Frère as “the Frenchman” (born in France he is Belgian by nationality and so listed in the race, driving one of several Jaguar D-Types). So far, so good, but a few sentences later a “Belgian D-Type” is finishing fourth. No [other] Belgian entries have in the preceding text been mentioned. So who is Smale talking about here? Frère, because he is Belgian? But he had crashed his D-Type on lap 3 and was DNF. A reader will only gain enlightenment by consulting a different source to learn that the D-Type on P4 was indeed a Belgian entry, piloted by Swaters/Rousselle—who are not mentioned in the 1956 coverage at all.

The point we’re making here is that just because a book has to be brief doesn’t mean it can’t be precise, especially if precision requires no extra space, only clarity of thought. (Speaking of that page, and of pedantry, there’s also a silly typo but you’ll want the satisfaction of finding that on your own, right?)

Copyright 2023 Helen V Hutchings (AACA, SAH) & Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter