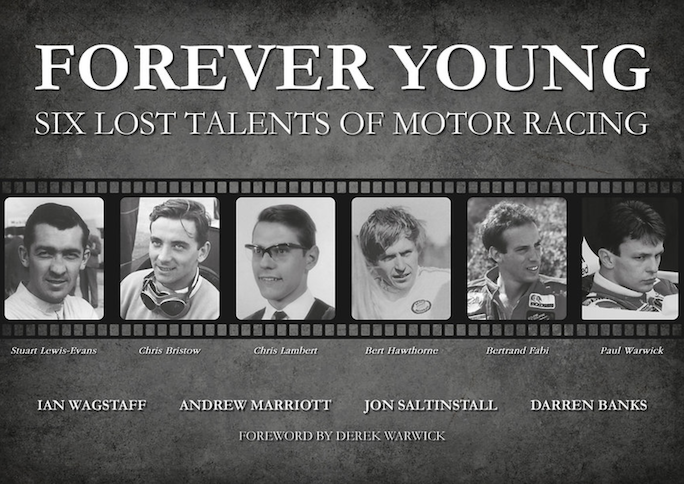

Forever Young: Six Lost Talents of Motor Racing

by Ian Wagstaff, Andrew Marriott, Jon Saltinstall and Darren Banks

“I found Paul a charming, modest and dedicated young racer . . . There was no question he had learned a lot from his big brother and I was starting to conclude that Derek was right, and that Paul was even faster than him.”

—Andrew Marriott, on Paul Warwick

Tom Pryce died in 1977 at Kyalami, in a hideous accident during the South African Grand Prix. But, if you read the race report in the next edition of Motor Sport, you wouldn’t have learned about Pryce until you had first plowed through a couple of thousand words. Racing driver deaths weren’t big news in the mid Seventies, they went with the territory, despite Jackie Stewart’s valiant campaign to make the sport safer. A campaign which more mature readers will remember was vilified by Motor Sport correspondent Denis Jenkinson. Deaths are still not unknown in the sport, but “only” one driver, Jules Bianchi, has died in a Grand Prix since Ayrton Senna’s death in May 1994.

The corollary of the welcome rarity of driver fatalities is that some drivers who have died at the wheel are almost beatified. The flawed Ayrton Senna enjoys an almost cargo cult level of adoration, and even far less successful drivers are lauded more post-mortem than during their careers, as if death itself enhanced their reputation. That isn’t healthy, and it was a trap I hoped the authors of Forever Young would avoid. The good news is that this book rightly celebrates the lives and careers of its subjects without becoming mawkish or sliding into too much “‘what might have been” speculation.

The six drivers featured here span nearly four decades, from Stuart Lewis-Evans (1930–1958) to Paul Warwick (1969–1991). The sport arguably saw more change during that era than at any other time, both in terms of car design and driver safety. Lewis-Evans and Chris Bristow now belong to a long-ago era of black and white, whilst Chris Lambert and Bert Hawthorne’s careers spanned the time when the sport echoed the huge cultural changes wrought by the Sixties and Seventies. As for Bertrand Fabi and Paul Warwick, their losses might still feel recent until you remember that, had he lived, even the latter would now probably be a retired fifty-something race driver.

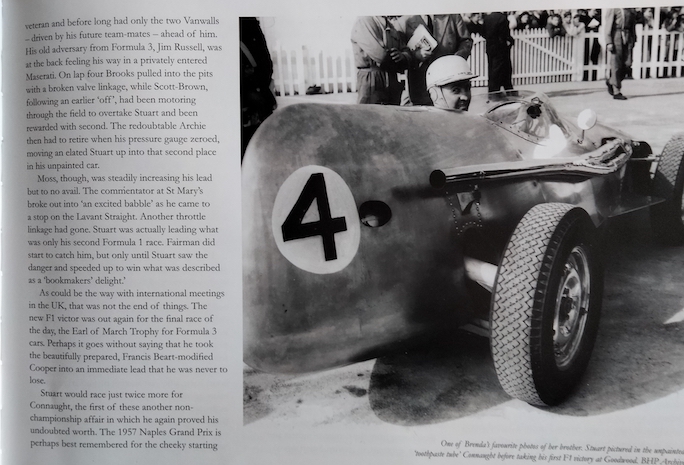

The four authors take different approaches to their subjects, possibly reflecting the diminishing resource of first-hand recollection in the cases of Lewis-Evans (above) and Bristow. Thus there is rather more emphasis on career than character, but I found there was still much to learn about the two drivers whose careers predated my own interest in the sport. I was intrigued that Lewis-Evans first raced in Formula 3 but was still competing in the same formula in 1958—unthinkable now, when FIA F3 is but a brief stepping stone for wannabe Formula 1 drivers. Stuart is now too often consigned to footnote status in Bernie Ecclestone anecdotes but “the little man with the big heart” (as Autosport’s obituary so patronizingly described him) deserves more. Driving sixteen hours in a Ferrari 315S at Le Mans in 1957 was proof of his mettle, and his love of his red and white Austin Nash Metropolitan ensured he didn’t conform to every race driver cliché.

And here’s that man Denis Jenkinson again, this time using his Motor Sport column to accuse Chris Bristow of being more fitted for stock car racing, “wild” and “uncontrolled.” Forgive me, but weren’t those the defining characteristics of at least one of Jenk’s later favorites? The fact that Bristow qualified his Cooper Climax on the front row of the Monaco Grand Prix in 1960 was testament to an underlying talent, but within a month Spa-Francorchamps had claimed another victim. Two in fact, as Alan Stacey was killed at the same race. How callous it seems to a modern race fan that the then prevailing stiff upper lip culture meant that the race was still run to its full distance . . .

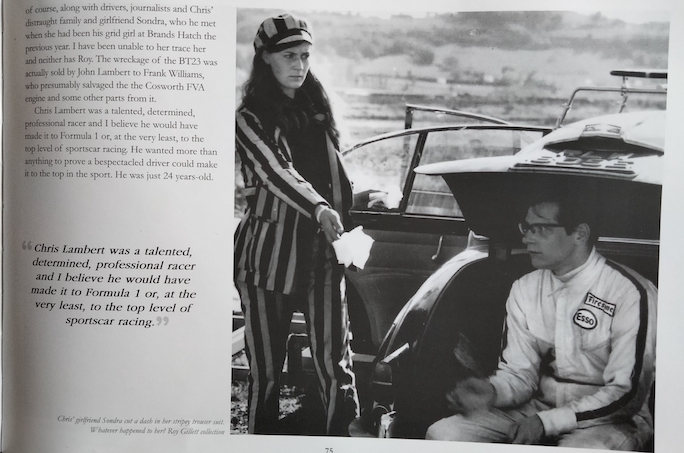

Andrew Marriott’s account of Chris Lambert (above) is informed by the writer’s friendship with his subject. He acted as Lambert’s “de facto manager” and shared “the famous motor racing flat at 8 Bolton Road” in Kilburn, North London with the Formula 3 racer and others. Many drivers in the golden era of 1L “screamer” F3 both looked and acted like vagabond gypsies as they criss-crossed Europe, racing in Finland one weekend and then 1000 miles south in Italy the next. But Chris Lambert looked exactly like the son of a chemistry teacher—which indeed he was. He also bore a strong resemblance to Team Lotus driver and jazz maestro, the late John Miles. Marriott has created a lovely portrait of the driver who was to die at Zandvoort in 1968, victim of Clay Regazzoni’s heat of the race impetuosity. The reminiscences of Lambert’s friends, Tony Dawe and Roy Gillett create an intimate and nuanced picture of a driver who had risked being forgotten. And if one is aghast at the over-prescriptive rule regime in modern racing, from track limits to profanity, how about Lambert’s penalty for “‘overdriving”—in a race he won from pole position? Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose . . .

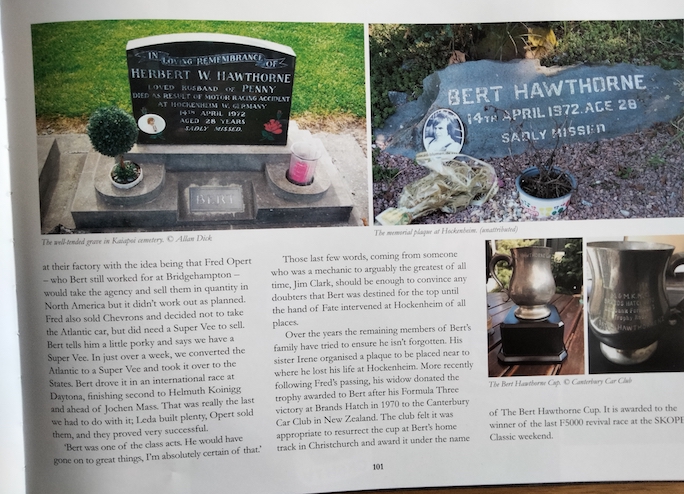

I’d forgotten that I had once seen Bert Hawthorne race in Formula 3, but I know much more about him now, after reading Darren Banks’ contribution. I learned that the New Zealander was what Brits call “a bit of a lad”—stealing parts for his Brabham BT 21 from his employer (also called Brabham) and getting up to the sort of high jinks for which F3 drivers were once notorious. But he was also a fast and serious racer who was beginning to touch the hem of the big time, only to lose his life at Hockenheim in his Tui in April 1972. An eerie echo of Jim Clark’s death, almost exactly four years earlier, also at Hockenheim and also in an F2 car.

Jon Saltinstall has form when it comes to driver biographies, as his definitive books on the careers of Niki Lauda and Jacky Ickx attest. His contribution on Bertrand Fabi is both insightful and moving, as is Andrew Marriott’s account of Paul Warwick, which concludes the book. If you’ve read Derek Warwick’s excellent autobiography (Derek Warwick: Never Look Back), memories of Paul will still be relatively fresh, but I can’t ever remember reading anything more than the Autosport obituary about the young Quebecois, Bertrand Fabi. I confess that I had forgotten how good he was. I had seen him race in Formula Ford 2000 but at the time I only had eyes for JJ Lehto (as you might have had if you’d seen his wet weather mastery). In the judgment of his FF2000 team boss Richard Dutton, Bertrand Fabi “. . . had an amazing talent . . . he was absolutely the calibre of Senna.” This view is endorsed by F3 boss Dick Bennetts who of course ran Senna in Formula 3. But it all ended at dusk on a miserably cold day at Goodwood, when Fabi’s Ralt failed to take the bumpy double apex Madgwick corner flat out.

The book is in landscape format and, although a modest 151 pages, it felt as if it were much longer, and in a good way. The illustrations are well chosen and serve not only as a record of race car evolution but also reminders of the transition of the sport from amateur to professional. Most of all, the book succeeds in celebrating the lives and achievements of its subjects without preoccupation on what might have been. That is the proper perspective to take, because Tomorrow Never Knows, right?

Copyright John Aston, 2025 (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter