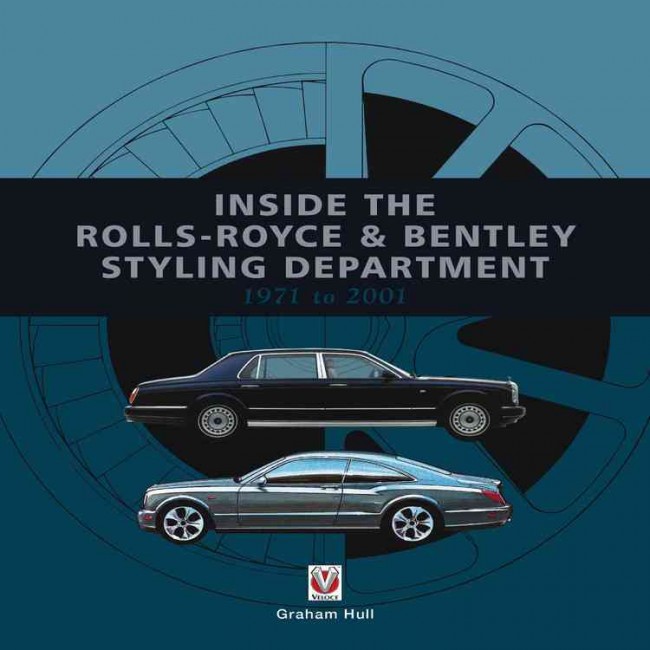

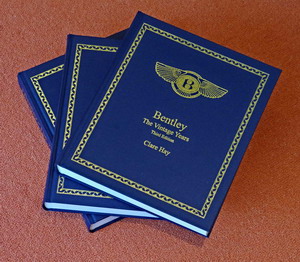

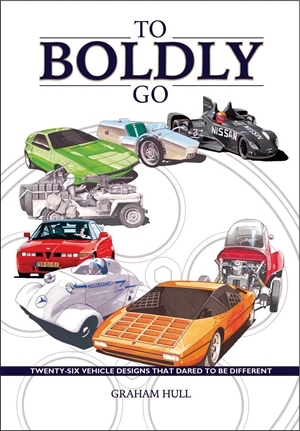

Inside the Rolls-Royce & Bentley Styling Department 1971 to 2001

by Graham Hull

“As memory can be selective or play tricks, I am happy to say that I kept desk diaries: not, I should add, in the interests of preserving information for posterity, but rather for posterior protection. Once it became known that you jotted down key developments or decisions, you had the upper hand in ‘who said what’ sessions.”

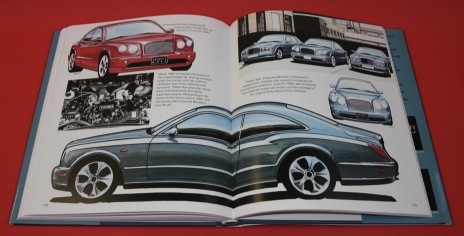

Firstly, a reviewer’s confession; Graham Hull’s superb drawings in this book give a chap pause for thought. I have before me Meccano Magazine for January 1956, which contains the information that one T. King of Christchurch, New Zealand, had won the June 1955 Overseas Motor Car Contest. That prize was One Guinea, that wonderfully archaic English measure of currency under which the better car dealers and tailors operated, and T. King spent it on virtually unobtainable Dinky toys, since New Zealand was operating under the Finance Emergency Regulations, 1940. He (I) had drawn a Mark VI Bentley in front of his idea of a Tudor English house, and of course his dream was to become an automotive designer, but that seemed to be impossible in this outpost of civilization, and life went on. Wheels were never T. King’s strong point, and whether or not he would ever have learned how to draw them does not matter; suffice to say that many hours have been spent admiring Hull’s drawings which grace his book.

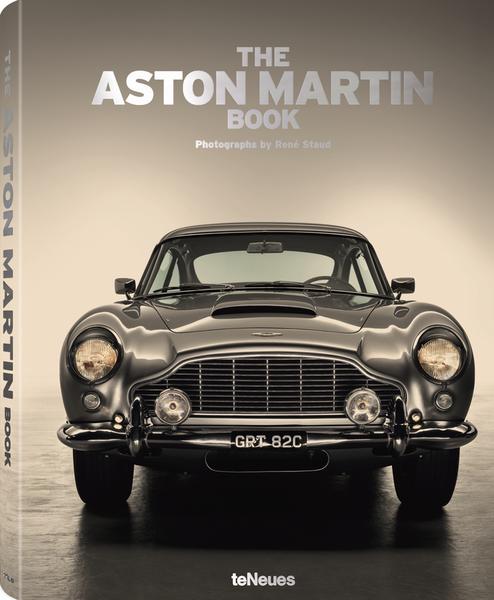

Rolls-Royce may build the finest of cars for the rarefied few but how they’re getting built is not necessarily any prettier than anywhere else. It may well surprise the reader who approaches Rolls-Royce with wide-eyed wonder to learn just what toughness was required to survive in this environment. Hull joined the company in 1971 at the age of 24, the son of an engineer who had worked for the long-established aircraft manufacturer Handley Page. Crewe seemed a forbidding world far distant from the Midlands, where the then British car industry was based, and much further from Hull’s north London origins. He was a graduate of the Royal College of Art, and here we start the bewildering array of acronyms that prevail throughout the book. RCA may mean, to many of us, the Radio Corporation of America, but Hull was a graduate of another RCA, where Chrysler U.K. had sponsored his study. By the time he graduated, Chrysler was contracting, and his alternative choice, Rolls-Royce Motors, had just declared bankruptcy after the development costs for the RB211 aero engine had destroyed its parent company, so this was hardly a good time for Rolls-Royce either. The British Government under Prime Minister Edward Heath rescued the company, splitting the aero from the car division in 1973 to be ready for privatizing. Vickers acquired the car company by 1980, their intentions of on-selling the enterprise obvious by 1994, but to German auto companies in 1998.

As well as its other qualities, the book is a fascinating account of the social problems that afflicted Britain in the last quarter of the 20th Century, with any idealism we enthusiasts for the marque may hold being dispelled by Hull’s vivid turn of phrase as he describes conditions, attitudes, perceptions (“The Engineering Department’s general opinion of ex-RCA graduates seemed to be that we were black belts in flower arranging”), and relationships that precluded the easy transition from models (built by salaried staff), to full-scale drawings, to full-scale mock-ups (built by hourly wage earners), meaning that designs took a very long time from idea to prototype. This did not matter in the traditional world where Rolls-Royce cars were created and other divisions of the company could subsidize them, but now the cars had to compete in a very different world.

By 1971 the Styling Department was led by an Austrian refugee, Fritz Feller, who had been an engine designer, and Hull became the sixth member of a team, succeeding Feller when he retired in 1984. The team’s task was to design the successor to the Silver Shadow on a VERY strict budget, with no thought of a Bentley successor to the T Type, by that time reduced to 5% of production, and a mere 3% when the line finished in 1979

The design of the Carmague was carried out by Pininfarina in Italy, and this radical design had been finalized by the time Hull started at Rolls-Royce. Its bulky appearance was mitigated by Hull and the Styling Department by their attaching markers to the front fender tops, “purloining” (in Hull’s word) the alloy wheels that one the then World Champion motorcyclist’s sponsors had made for his Silver Shadow, and creating a slightly nose-down and tail-up stance. David Plastow, the Managing Director, was won over by this approach, and Hull’s influence in design was cemented, although the usual arguments with Engineering over their concerns regarding alloy porosity and corrosion meant that steel wheels continued to be fitted until 1985 and the Bentley Turbo R.

Hull and Ron Maddocks, the model-making member of the Styling team, created a sort of “lunch-time” Bentley project derived from a futuristic drawing that Feller commissioned for presentation to Plastow, and Hull had “one of my better ideas” when “Mulsanne,” a reference to Bentley’s grand Le Mans heritage, was written on the rear license plate. The name was registered, and one of Feller’s associates, Jack Read, developed the turbocharged version of the company’s V8. The radiator shell was painted rather than plated, and because of social issues which included new top management who were not happy with the intimidation nature of the Rolls-Royce marque, a new product evolved from the Bentley T Type, with contributions from Styling, Marketing, and Engineering, which became the Bentley Turbo R. In the same way that the Mark VI saved the company in 1946, so the Turbo R took the company, and the Bentley marque, in a new and exciting direction.

One chapter is named “The Drama of the 1990s, a golden decade of bespoke coachbuilding,” with an account of the prototype Bentley Continental R appearing at the 1991 Geneva Motor Show, and the Sultan of Brunei wishing to buy it. That car may well be the most recent example of the marque to be regarded in the future along with the R Type Continental of 45 years earlier, but the royal family of that oil-rich little land became quite good customers of Rolls-Royce Motor Cars, contributing about half the revenue of the entire company between 1994 and 1997, to the value of some $400 million dollars a year in 2014 value. Information about the 2000 or 3000 cars in the royal garages circulates quietly, with chassis numbers of Bentley models otherwise unknown to us. The Java project that appeared at Geneva in 1997 was another exciting project, based on the BMW 5 Series floor plan, and the close relationship between the two companies was undoubtedly a factor in the purchase of the Rolls-Royce bit which went to Munich ownership.

Volkswagen ownership of the Crewe factory brought new organization and a different ledge for Graham Hull, from which he eventually retired in 2001. He seems a likeable man, one whom one would be privileged to meet, and he has certainly given us some classic automobiles, while playing a large part in providing continuity through a turbulent era.

A great deal of information is present in this book; the problem is in assimilating it all. Chapters cover the same ground, but from a different aspect, the chronology is all over the place, and the cast of characters will have the reader looking for more bookmarks. Shoddy proof reading has resulted in “Groucho Marks,” “flair up” and “lent back,” while “myself” is its usual irritating substitute for “me.” The book is presented to the usual Veloce standard, with clear typeface and good quality reproduction of images on good-quality heavy paper, and well bound.

This view from the “inside” is a valuable contribution to our knowledge of a company that has built super premium luxury cars for over 110 years of unbroken history.

Reprinted in 2019 without material changes as a softcover.

Copyright 2019, Tom King (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter