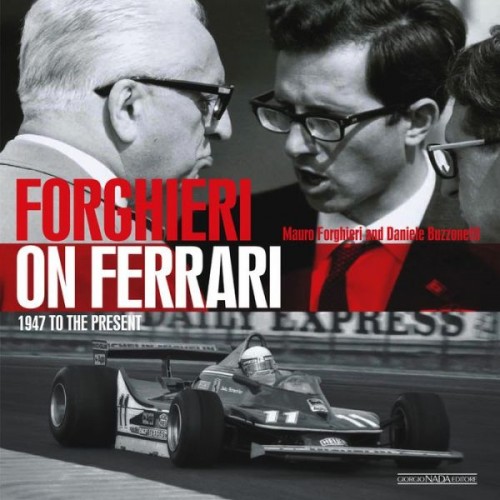

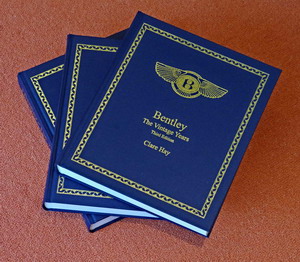

Forghieri on Ferrari: 1947 to the Present

by Mauro Forghieri & Daniele Buzzonetti

by Mauro Forghieri & Daniele Buzzonetti

His quarter-century tenure at Ferrari as engineer and sometime team manager have given Mauro Forghieri (b. 1935) a prominent place at the core of the marque’s ethos and philosophy but he is rightly known outside of Ferrari circles as well thanks to his work for Lamborghini and Bugatti and, presently, his own Oral Engineering firm that designs and constructs prototypes as well as mechanical bits for all sorts of go-fast machinery.

If you know your Ferrari history you’ll recall that two Forghieris have a place there. It is in no small measure due to Enzo Ferrari’s respect for Mauro’s father, Reclus (b. 1912), who had worked there since the early days and rose to be head of the mechanical workshop, that Enzo himself talked Mauro F. out of seeking a career in aero engineering (in America no less) and hired him fresh out of school. In no time at all, and for reasons entirely beyond his control, Mauro was appointed technical chief of the racing department at the impossibly young age of 26 after the wholesale sacking of the Ferrari management team in the wake of the “Laura Scandal.” This alone would make an honest, insightful book by such an insider highly desirable. Except for Enzo’s own autobiography—which is colorful but strays from objective truth—most of what we know has been written by outside commentators.

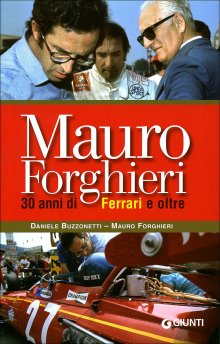

But if you know your Ferrari literature you’ll recall that there was already such a book, and not long ago: Mauro Forghieri: 30 anni di Ferrari e oltre (“30 Years of Ferrari and More”) published by Giunti Editore in 2008 (ISBN 978-8809062092). It too had journalist and Ferrari expert Daniele Buzzonetti’s name in the byline. The world was not impressed . . . it was widely seen as a failed—and wasted—effort, the concern being that such specialized subjects do not get revisited. The more charitable souls attributed its superficiality to Forghieri, then 75, being too preoccupied with his Oral Engineering projects. Moreover, that book was only ever published in Italian. So, anyone with a memory might look at this new effort—by the same people about the same subject—with skepticism.

But if you know your Ferrari literature you’ll recall that there was already such a book, and not long ago: Mauro Forghieri: 30 anni di Ferrari e oltre (“30 Years of Ferrari and More”) published by Giunti Editore in 2008 (ISBN 978-8809062092). It too had journalist and Ferrari expert Daniele Buzzonetti’s name in the byline. The world was not impressed . . . it was widely seen as a failed—and wasted—effort, the concern being that such specialized subjects do not get revisited. The more charitable souls attributed its superficiality to Forghieri, then 75, being too preoccupied with his Oral Engineering projects. Moreover, that book was only ever published in Italian. So, anyone with a memory might look at this new effort—by the same people about the same subject—with skepticism.

Well, fear not. This new book is not cheap but totally worth it and it’ll settle many questions. As the longest-serving Ferrari engineer, Forghieri can offer insights into politics, colleagues, drivers, finances, hard-core technical matters and, of course, The Man himself. In life he is an amiable and modest man and in the book his commentary never strays from poignant, when apropos, into strident. The high and low, the good and bad, mistakes made and lessons learned—it’s all part of a day’s, a life’s work. Gian Paolo Dallara, his colleague for a short while (later of Miura fame and many, many other high-level accomplishments), wrote the Preface and calls Forghieri’s career “unrepeatable” because of the culture that prevailed at Ferrari in those days.

That Preface, though, is indicative of a shortcoming very often found in this publisher’s books: an utter lack of imagination on the editor’s and designer’s part as to how a reader will “work” with a book. This is so entrenched that one must assume it is done not out of ignorance but willful disregard. The books are always nicely presented in terms of typography, design elements, use of space etc. but it’s the little things . . . the Table of Contents, for instance, says the Preface is by Dallara so you start reading it—only to begin to wonder why it is about Dallara. All the type on the page is the same—font, size, color, leading—so you’ll have to puzzle over this until you make it to line 14 where an opening quotation mark is your only cue that the narrative is shifting from an “Editor’s Note” introducing Dallara to the actual Preface-writer introducing Forghieri. This is not user-friendly and not clever. Worse, the same lack of clarity applies to the Forghieri text that is the result of hundreds of hours of interviews: some parts are in quotes and therefore obviously his but embedded into text that, presumably, Buzzonetti wrote. In other parts you have to wait for a personal pronoun (“and when I switched to the V-12 . . .”) to establish who is speaking or wait for a parenthetical note by the editor (the first one doesn’t occur until p. 41). Considering the enormity and precision of the detail in the general narrative, it almost defies reason to think Forghieri could have had this sort of recall and that it isn’t the editor tying various strands together. This becomes even more ambiguous in a translated text where neither voice has its original tone, idiosyncrasy, or flow. (Robert Newman whom US readers may know from his column in Vintage Racecar Journal did translator duty.) Long story short: help the reader!

Such is the level of detail that once you start reading you’ll be surprised how long it takes to get through the book. And the hours spent reading will pale in comparison to the hours of discussion that will ensue! Also, there’s no Index so you’ll be scribbling your own notes. There are typos here and there but nothing glaring, the worst one probably being a figure caption (p. 261) whose legend calls out 10 items in a drawing that contains 11 and also mislabels one of them.

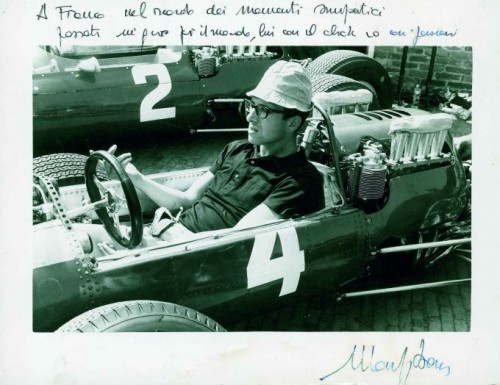

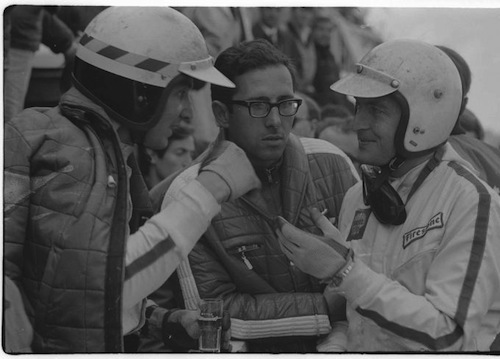

Photos are plentiful, often large, well reproduced, many previously unpublished, and splendidly captioned. There are several b/w technical drawings and cutaways, even an entire (reduced) blueprint as well as reproductions of Forghieri’s handwritten notes. The illustrations from 1989 onwards are by Giorgio Piola in the style of, or possibly reproduced from his many books.

Lest you think this book is all about Forghieri blowing his own horn, realize that his hometown of Modena mounted an exhibit in 2011 celebrating his outstanding accomplishments, “L’Ingegner Forghieri: la furia dei motori. Trent’anni di Ferrari ed oltre,” that brought together many of his designs and cars loaned by important collectors.

Copyright 2014, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter