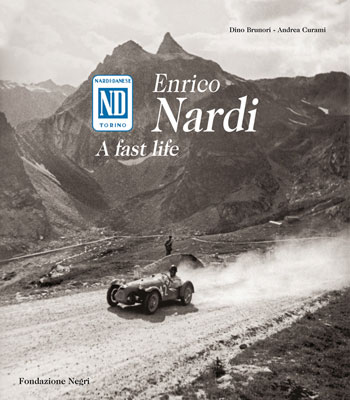

Enrico Nardi, A Fast Life

by Dino Brunori, Andrea Curami

by Dino Brunori, Andrea Curami

Enrico Nardi would probably be amused at the attention he continues to receive some 43 years after his death in 1966. More at home in the shop than in social situations, money, fame, or gold watches did not impress him much. One day, a well-dressed foreigner arrived at Nardi’s tiny garage in Turin, condescendingly asking a mechanic in coveralls to speak to the master. The mechanic sent him into the boss’s office, home to the shop’s growling Alsatian watchdog, Pal, and locked the door. “Let the mastereducate this chap,” he told his buddies and left the hapless visitor to work things out for half an hour with the dog. The mechanic was Nardi himself, a born practical joker who had once taken his daughter Roberta to the Paris Exhibition and passed the beautiful young girl off as his fiancé—much to the surprise of those who knew Nardi as a married man.

Roberta (d. 2006) herself was eager to help the authors and provided background and several photos for this book. Brunori puts together enough anecdotes about Nardi to give the reader a fair grasp on what made Nardi—and his products—famous, literally getting Enrico Nardi out from behind the legendary steering wheel. He depends a great deal on interviews with old Nardi veterans Gino Munaron (d. 2009) and Gino Velanzano to provide background information. Nardi was, Brunori writes, “meticulous, stubborn, quarrelsome, hot tempered but also courageous.”

Famed as he was for accessories and in particular, steering wheels, Nardi was also the driving force behind some sixty unique racing, sports, grand touring, formula and show cars. Brunori covers just about every one, and describes Nardi’s relationship with both Vincenzo Lancia and Enzo Ferrari before the war. Weaving Nardi’s sparkling personality between the cars he helped create, Brunori tracks down the successes drivers of the NDs—Nardi-Danese cars—achieved. It is a fascinating and human story of one of Italy’s postwar “miracles.” The book’s scope goes far beyond Franco Varisco’s slim 1987 volume Nardi, A Story of Cars and Steering Wheels. Brunori is the first to admit that he is neither a writer nor a historian. “I’m an architect and run a small retail design firm. Nardi is my first (and probably last) work. Only passion drove my efforts.” In fact he asked the Italian historian Andrea Curami (who has a long string of auto books to his name) to help with the book. The result is a passionate story, in roughly chronological but somewhat arbitrary order. One example: Nardi’s first car makes it appearance on p. 30, in 1947, then on p. 94, in 1951 now converted to a Giaur by way of Taraschi. In 1952, on page 106, we find the now Crosley-powered car in the hands of Frank Dominianni. It all makes perfect sense if read chronologically, and in fact is a joy to read through. But without an index it makes things a bit difficult. According to Brunori the reason there is no index is that the Italian original which does have footnotes and a good index ran to 200 pages and the publisher needed to cut the English version, which ran a bit longer, to the same size. Does this matter? Academically yes, realistically no. If you like the subject matter and Etceterinis in general, and don’t speak Italian, the lack of an index does not outweigh the book’s merits. For instance, all of Nardi’s many 1947–1957 races are recorded by date; by name, class, model, chassis number, and car number; and by driver/codriver and finishing position.

The English version displays a remarkable sense of humor in the writing. Brunori explains that he specifically asked the translator, Paul Etgart, to preserve the tone of the original. For the chassis information, the fine hand and mind of John de Boer came to the rescue. He sorts out the various Nardi cars and how they were numbered and the author credits him, and others, with unraveling the still poorly documented US presence of Nardi cars.

After 198 interesting pages full of unpublished photos, descriptions, ads, and race statistics, Brunori divulges a tragic fact—in the 1970s, the Nardi family pulled out of the business entirely, and the new owners threw almost everything away. Brunori salvaged what he could and a good deal of that material found its way into this book.

Copyright 2010 (speedreaders.info).

(Adapted, with permission, from a review by Pete Vack who first wrote it for his website VeloceToday.com of which he is Publisher and Editor and where this book can be ordered in the US.)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

Newsflash: Curami died June 24, 2010.