Bentley “Old Number One”

by Michael Hay

by Michael Hay

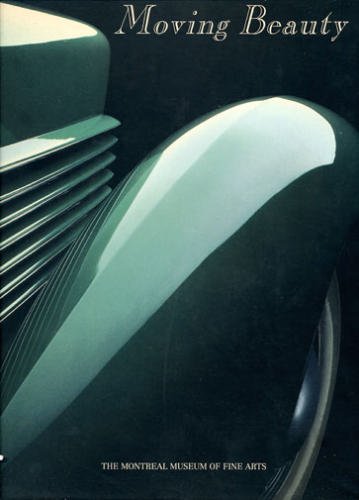

Old Number One was the most famous of racing Bentleys—chassis LB2332 completed in May 1929. It was the personal property of Woolf Barnato, prepared for racing in Bentley Motors’ racing shop at Kingsbury, which was leased from Vanden Plas who owned the premises. The car was still around in 1990, restored to 1932 Outer Circuit form. This book ends with Chapter Five, Hubbard v Middlebridge Scimitar, and this is where we will begin—with the story behind that chapter. Bear with us for just a moment.

In 1989, the owner of Old Number One, Edward Hubbard, had expressed an interest in buying Middlebridge Scimitar, the manufacturer of Scimitar motorcars. The deal between the parties provided that the former would acquire all the assets of Middlebridge, valued at £3.2 million sterling, plus an additional £6.8 million in cash, in return for which Middlebridge would receive title to Old Number One. In other words, Old Number One was valued at £10 million. This is how matters stood in early 1990.

Coincidentally, in the May 1990 issue of the Bentley Driver’s Club Review, your reviewer proposed “three tests” to determine how far back in time a badly abused Bentley could be legitimately restored. This was in response to a plea from Bob Reed (then of Geneva, now Rhode Island) concerning his recently acquired ex-George Porter/May Millington flat-radiator 3 Litre, rebuilt after Porter’s fatal crash as a Blower 3 Litre and finally, as acquired by Bob, unblown. Anything but original. The burden of Bob’s enquiry was should the car be returned to flat radiator or blown form?

The “three tests” showed that his car, FR5189, could legitimately be returned to Blower 3 form, in which it now is—the only supercharged 3 Litre to leave Cricklewood. As a further example of the substance of the “three tests” chassis LB2332, Old Number One, was considered, and shown to be legitimately restorable to 1932 Outer Circuit form. Uncannily, this was written in complete ignorance of the return of Old Number One—by now a boy racer—to England from the United States, its purchase from Stanley Mann by Ed Hubbard, and the latter’s restoration of the car to 1932 Outer Circuit form.

These two chains of events then converged in the Royal Courts of Justice in London, where Hubbard v Middlebridge Scimitar was tried before Mr. Justice Otton. Middlebridge, the defendant, had failed to perform on its contract with Hubbard, and the latter was suing for completion. Middlebridge’s defense, in a nutshell, was that the car had been misrepresented since clearly it wasn’t Old Number One, the 1930 Le Mans winner, thus was of little historical interest and worth only £250,000.

Chapter Five details the High Court’s reasoning in finding in Hubbard’s favor. Michael Hay, the author of this book, well known as the leading chronicler and now forensic historian of vintage Bentleys, withstood three days of cross examination in support of plaintiff’s contention that the car had been properly described as “Old Number One.” Mr. Justice Otton found that the “three tests” did indeed support the restoration of the car to 1932 Outer Circuit form. There was, of course, much else besides entered in evidence and Wally Hassan himself gave testimony. All this is exhaustively explained.

The preceding chapters, first to third, lay the groundwork for W.O.’s decision to re-enter racing with the six-cylinder car after Barnato’s rescue of the company, and they examine the 1929 and 1930 racing seasons principally at Le Mans and concentrating on LB2332. Chapter Four follows with the post-Le Mans era on the Outer Circuit at Brooklands. This microscopically detailed history of the car embraces much of overall Bentley racing to put the subject car in proper perspective. There has probably been only one previous book of such authority about a particular Bentley: Tim Houlding’s history of 3 Litre Experimental Number Two.

Of the many new photographs never before published, one in particular caught this reviewer’s eye: Old Number One standing outside the racing shop at Kingsbury. It is interesting because Rivers Fletcher, in a caption in his 1982 book Bentley Past & Present, had identified a photograph of the prototype 4½ Litre ST3001 in the exact same spot as having been taken at Ardenrun, Barnato’s Surrey home. I had always been dubious about the identification because it certainly didn’t match my recollection of Ardenrun from visits there. I had suspected Kingsbury, but neither Tim nor I were ever able to confirm this. Now Michael Hay has.

The scholarship displayed in this book is astounding. To quote but one instance, in a caption: “The large holes visible in the side-rails just behind the gearbox are for the team car pattern front brakes. These prove that the side-rails were repaired, and not replaced, after the crash in the 1932 500 Miles race,” the crash in which Clive Dunfee was killed. Even more astounding is the fact that Hay published this book from his home, while concurrently entering wedded bliss and becoming a father!

One is pained to note several typos, probably caused by this reviewer (note: this reviewer refers to Hugh Young as identified in copyright info below) not being asked to correct the page proofs as he did for Hay’s Bentley Factory Cars. Thus—and I am sure Hay will take this in the spirit in which it is offered—neither Barnato Walker nor Kensington Moir should be hyphenated (in the latter case, Bertie was given his mother’s maiden name as his middle name); the quotes within quotes would bear scrutiny; the accent is missing from Montlhéry; there is a simple typo on page 13, and another on page 76; the fractions would be improved had they been set bold; and so on. No one would ever notice these things if they weren’t mentioned here, and they do not in any way reflect on the authority of the book’s substance.

One is happy to report that in 1999 after all this drama Old Number One survives still—as restored to 1932 Outer Circuit form, and utterly desirable. In sum, an accounting of one car researched with monastic devotion, and the vital significance of a landmark legal decision, which closes the book. You can’t be seriously into vintage Bentleys if you pass this one by.

Copyright 2009, Hugh Young/Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter