Amateur Racing Driver

by T.P. Cholmondeley Tapper

by T.P. Cholmondeley Tapper

My recent reviews of Bugatti books sparked a memory of a New Zealand driver (1910–2001) who got his start on that marque, and who wrote an autobiography in 1954; it was a pleasure to re-read, hence this review.

As a teenager in Christchurch, New Zealand, I was nonplussed by the opening sentences of the book’s Conclusions: “The early years of my life were spent in New Zealand . . . in Christchurch, and our house was situated on the outskirts of that city with a large garden extending to the banks of the river Avon.” Within a mile of my parents’ home was Cholmondeley Avenue, and I knew enough of the idiosyncrasies of English pronunciation and the nuances of their class system to say “CHUM-ley,” which doesn’t help settle the matter of whether his near contemporary, racing driver and jazz musician Rupert “Buddy” Featherstonehaugh (1909–76), is “FEAST-on-hay” or “Fan-Shaw”?

At any rate, the T.P. bits of the author’s name are Thomas and Pitt, and he is linked to the noble families of Rocksavage and Delamere. Although there is a reticence throughout Amateur Racing Driver, he seems to have been a sociable person; friends’ names are seldom mentioned.

Despite this understatement, from a birth in 1910, departure with his parents to England at the age of 14, passing the Entrance Examinations for Cambridge University at 16, and having to spend two years at Grenoble Université before he reached the minimum age to study law at Jesus College hints at a fearsome intellect. Poor dear, he had to spend that time skiing, becoming proficient enough “to win several ski races, and was chosen to be a member of the team of four to represent Great Britain in the World Ski Championships held in the early months of 1937.” Access to Grenoble ski-fields required an 0500 start, a 3-mile walk carrying skis and gear to catch a tram for 25 miles, and an 8-hour climb to the Refuge l’Alpe d’Huez base for the skiing.

Before he left New Zealand he had tinkered with an old horizontally-opposed twin Douglas motorcycle, and taught himself the rudiments of that primitive suction-valve engine. Taken by friends to Brooklands Track in 1931, “At the end of the day I sat in the car on the return journey, my head still ringing with the penetrating noise of the engines and full of ideas of becoming a racing driver, privately nursing a conceited opinion that without much difficulty I could perform as well as most of the drivers I had seen that day.”

Simpler times . . . he dashed off a letter to one Ettore Bugatti, offering his services as a team driver for the next season but admitting his lack of experience. No reply was forthcoming, so he searched for a suitable car. After a hair-raising trial run through London streets he selected a used Type 37 Bugatti, a 1496 cc with a stark two-seater body, well-worn after five years of spirited use. He found that he could cram himself with two friends and luggage aboard for a skiing trip to a Scottish winter.

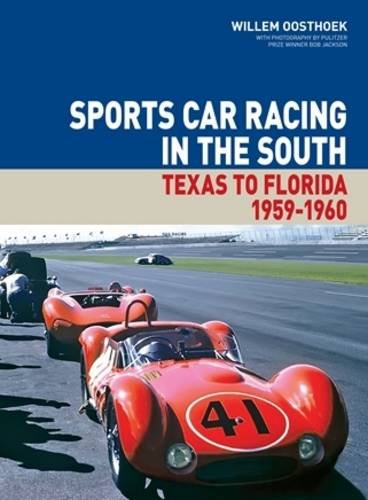

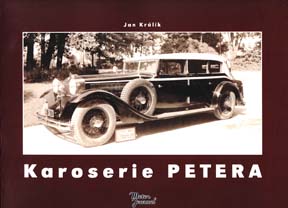

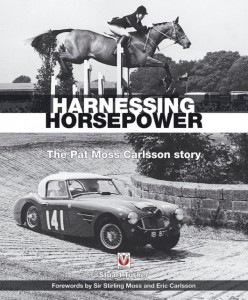

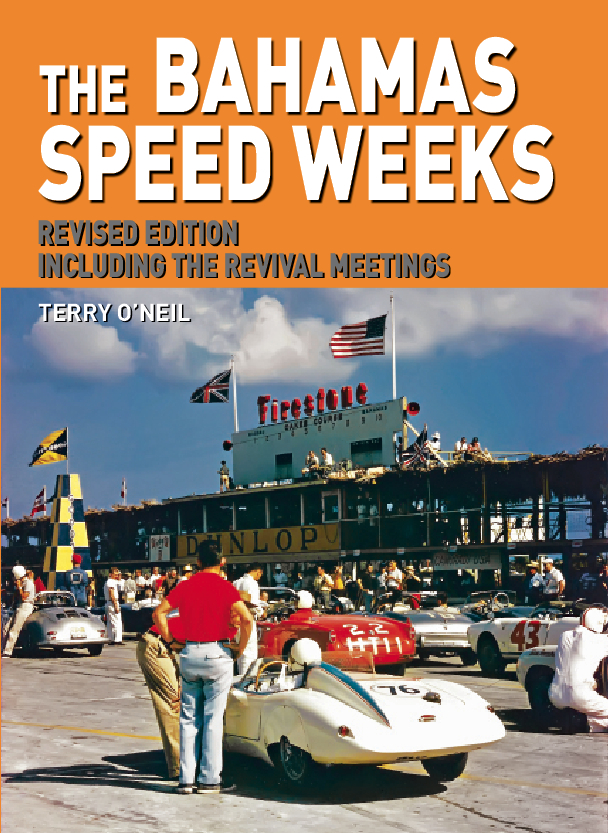

Autumnal gloom at Donington Park in 1933. Tapper is on the right in his white Bugatti, number 19 painted by an amateur.

The engineering skills he had taught himself as a schoolboy seem to have been adequate to rebuild the engine to an uprated form after a few hill-climbs, and he entered his first race at Brooklands in July 1932. Tapper’s account of competing there and at Donington Park (right), as he recorded his memories of that now remote era, are fascinating.

Competitions in Europe from 1934 beguiled him, and with a letter of introduction from Bugatti’s London agent, “one came upon a pleasant château, . . . and, beyond, the group of buildings which comprised Usines Bugatti. I entered the colonnaded gates, presented my letter, and was asked to wait while someone was sent to show me around. While I did so I was amused to see Jean Bugatti, the eldest son of the family, pass in and out testing various cars. He would approach the factory gates at tremendous speed while two men would rush to open them and signal him through if the road was clear . . .. Soon he would reappear from the opposite direction, heralded by the whine of a supercharger and travelling at an alarming pace. Once again the men would rush to open the gates . . .. As far as I could see, anyone who wished to speak to him had to do so while trotting at the side of the car, purposely slowed, and when the conversation was at an end, Jean would abruptly accelerate fiercely away from the somewhat dumbfounded speaker.” Tapper was taken for a very spirited ride aboard a 4.9L racing Bugatti, and his first-hand accounts and descriptions of Ettore Bugatti’s fiefdom, relatively fresh in the author’s memory, bring events of more than 90 years ago into focus.

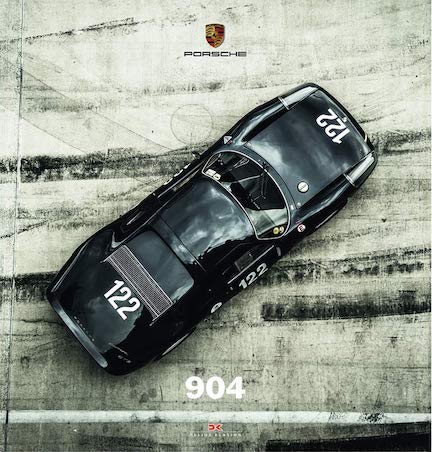

Tapper’s Lancia towing his Bugatti en route to Freiburg in 1934.

European events attracted Tapper from 1934 (where were his university studies? although his business career at Lloyd’s of London after he retired from motor racing infers some seriousness) and starting money was often enough to cover his expenses. An old Lancia Lambda was his tow-car from disembarkation at Antwerp to Freiburg, the base for a 7.5-mile and 2700-feet climb through 173 corners. The Prix de Berne for 1.5 liters and the Grand Prix in Switzerland were next, and here such eminent racing drivers as von Stuck, Caracciola, Dreyfus, Varzi, Chiron, Veyron, Howe, Seaman and Fagioli, as well as holders of European nobility were encountered.

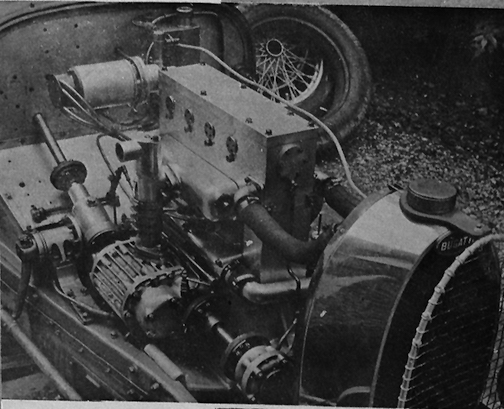

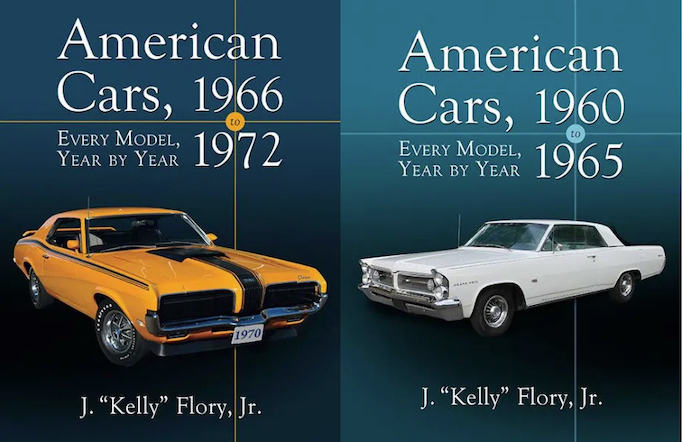

Type 37 Bugatti engine now converted to supercharged “A” form.

Outclassed, the Bugatti’s engine was turned, more or less, into the “A” specification by addition of a secondhand supercharger, although the single breather rather than the four of the Works cars meant that Tapper’s car would throw its oil out when pressed hard; hardly suitable for serious racing. By the next racing season his towing car was an old Type 40 Bugatti, and that similar 1496 cc had to propel about 2 tons of Type 37A, parts, and trailer. The Bugatti Works rebuilt the 37A engine, but there is no mention of the cost. He competed at the Nürburgring in 1935 and 1936, and acquired a Maserati from Earl Howe that he raced in Europe, England, South Africa, and Ireland. When faced with a decision, the prohibitive costs to continue as a competitive amateur, a test drive offer from Mercedes with a possible Team membership, and after yet another bad skiing accident which rendered him unfit for RAF service, he decided to retire from motor racing after the 1937 season.

The last two chapters are devoted to theories of racing driving and philosophical conclusions, signed off from his home in Buckinghamshire at the age of 43. (The book has an Index.)

T.P. Cholmondeley Tapper peeks from his writing as a modest and reticent survivor of somewhat brutal sports, and his account gives us a window into an era that finished almost 90 years ago. His wartime flying for the Air Transport Auxiliary and his acquisition of land sufficient to accommodate an aerodrome, later to become RAF Haddenham, are not mentioned.

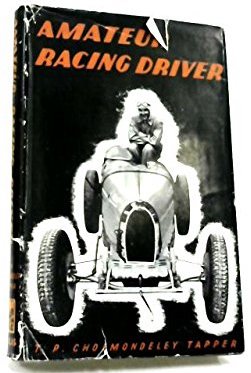

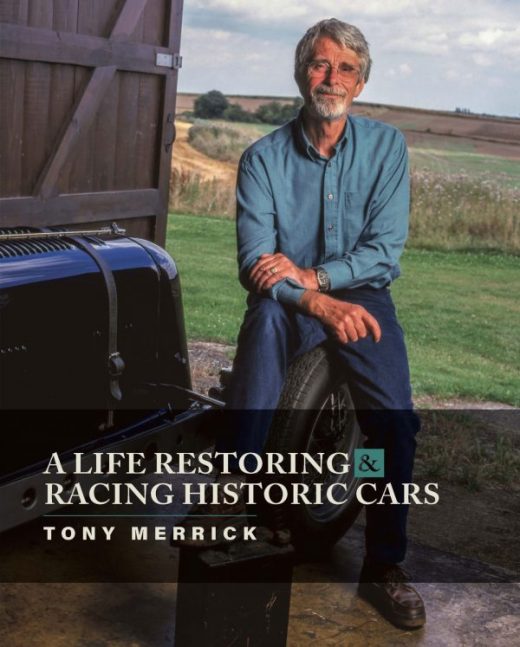

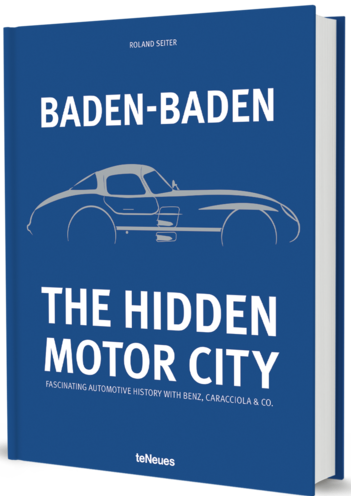

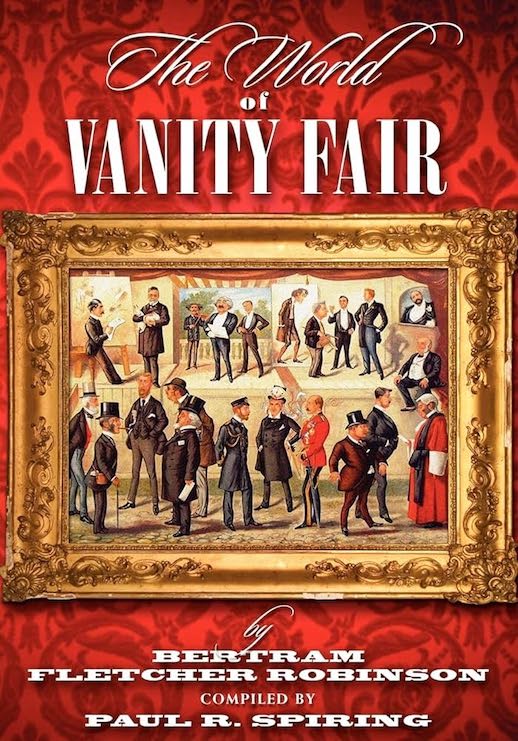

The 1954 first edition by Foulis probably had this dust jacket.

- As a footnote, the review copy is No. 16 of the reprints by Motoraces Book Club which was active ca. 1963–67 as part of the Readers Union group of book clubs which was owned by JM Dent & Sons (Aldine House, 10-13 Bedford St, London WC2). They released about six titles a year, for a total of 32 or 34 books, most of them numbered. There is no ISBN reference, but the book is not rare and may easily be found.

Copyright 2025, Tom King (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter