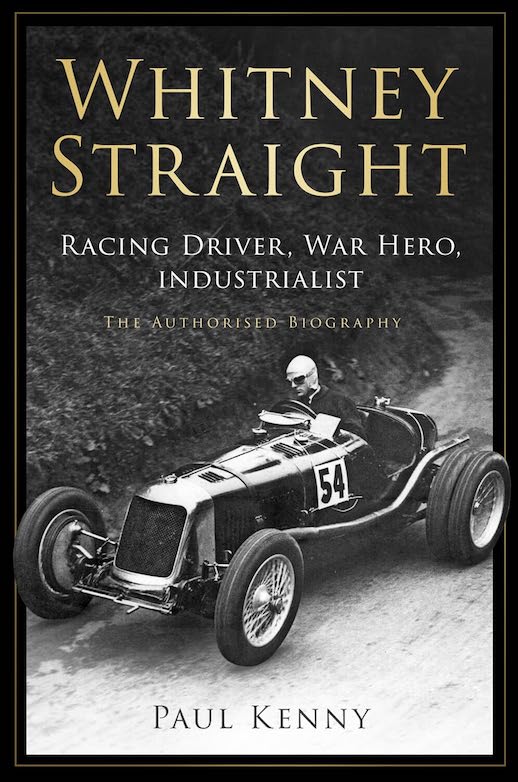

Whitney Straight – Racing Driver, War Hero, Industrialist

by Paul Kenny

by Paul Kenny

“This book is the story of the young American boy who read that letter, the English gentleman he became and the extent to which he heeded his father’s advice.”

When I reviewed Richard Williams’ excellent 2021 book on Richard Seaman (A Race with Love and Death), in which Whitney Willard Straight featured, I imagined him resembling Rex Mottram in Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited. Rich, supremely confident and street smart but, as an American, also gauche, and not fully house trained. Assuming, that is, that the house in question was an English country house populated with characters who’d escaped from a PG Wodehouse novel. Chaps called Tuppy and Bingo, gals called Corky and Honoria.

But as I read Paul Kenny’s extraordinarily detailed biography, I realized that Whitney Straight reminded me more of Logan Mountstuart, whose long life was chronicled in William Boyd’s novel Any Human Heart (2002). Mountstuart was the man, just like Straight (b 1912), who experienced at first hand the seismic events of the 20th century, and who mixed with the men and women who shaped that most turbulent century. And, just like his fictional counterpart, Whitney Straight was driven, complex, flawed and, like Tennyson’s Ulysses, a man who “drank life to the lees.”

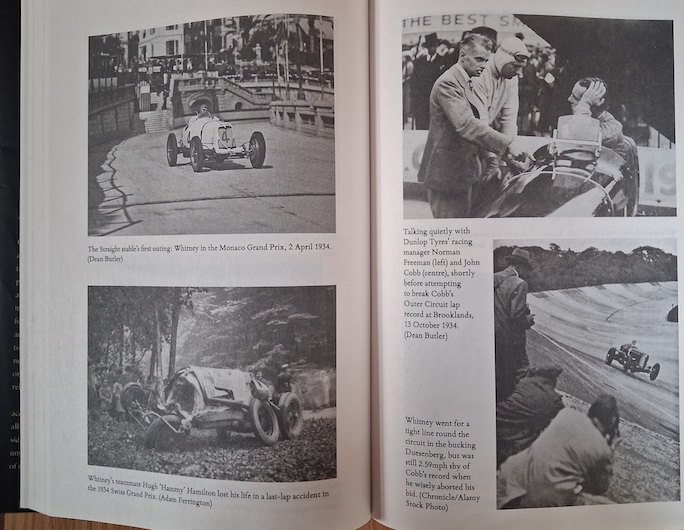

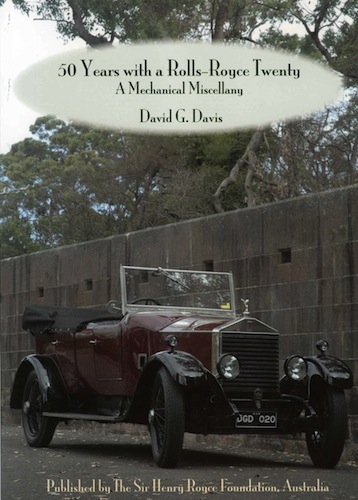

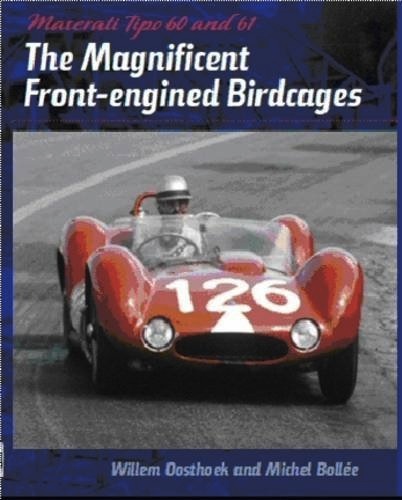

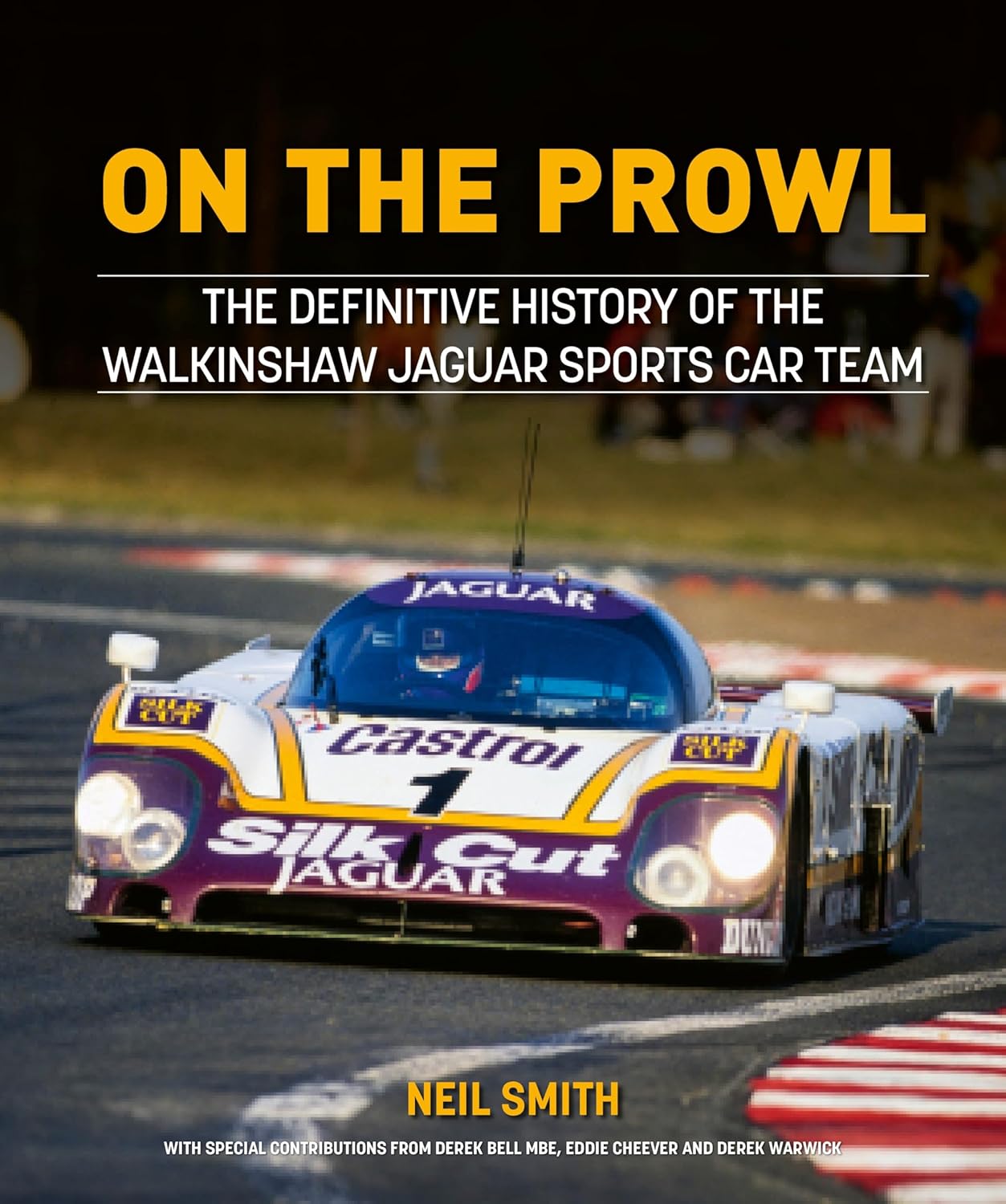

As the book’s title states, Whitney Straight had three careers. He was a successful racing driver and team owner in the 1930s, as can be seen from the wonderful image of Straight’s Maserati at Shelsley Walsh hill climb in 1933. He then had what men of his generation termed A Good War. Next, the Thirties’ entrepreneur blossomed into a serious mover and shaker in postwar Britain, becoming boss of BOAC [1] and vice-chair of Rolls-Royce, while also holding a host of other roles in UK commerce.

As Straight’s authorized biographer, Paul Kenny enjoyed access to the family archives and photographs and conducted years of research into his subject. 376 pages mean that this isn’t a short book, and the small font (legible, but mercifully it’s no smaller) makes it feel like a significantly longer read. And it needs to be, because a shorter book would struggle to contain such heavy cargo, risking sinking from the sheer weight of information. To give an idea of the academic nature of the work, there are 13 pages of notes, a seven-page bibliography and (hooray) a proper index. Kenny, incidentally, was both a practicing accountant and a trained archeologist so no stranger to minutia. But I bet Mrs. Kenny broke out the champagne when her husband finally said he was done with Whitney!

Willard Straight, Whitney’s father, died just after the end of World War One, of Spanish flu, but he was clearly a man with a future. There’s maybe even a distant echo of John F. Kennedy in the text of the letter Willard addressed to his son in 1917. Extracts from the letter now surmount the fireplace in Cornell University’s Willard Straight Hall and it is this letter that is referred to in the quotation preceding this review.

Straight had an unusual upbringing in a family far removed from that of most stereotypical Thirties’ gentlemen. His education was at Dartington, in England’s south-west, the pioneering liberal arts school established by his mother and stepfather. And although Whitney became more conservative as his business career progressed, his family remained socialists, and his brother was even a communist for a time. Whitney’s family money springboarded him into motorsport when he was a student at Cambridge but, unlike some of his peers, he was no dilettante; he soon established himself not only as an accomplished driver, but also as a professional team boss for drivers who included the aforementioned Richard Seaman.

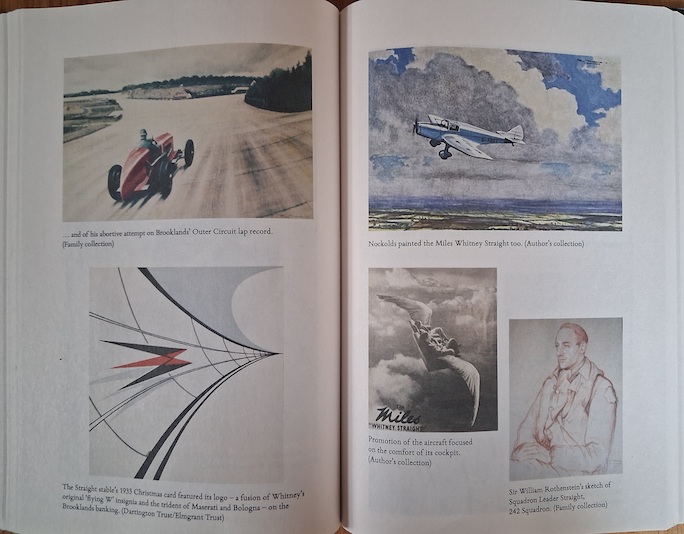

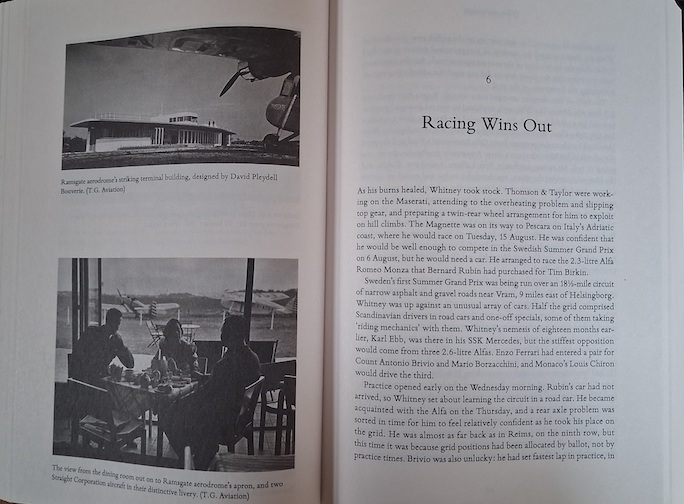

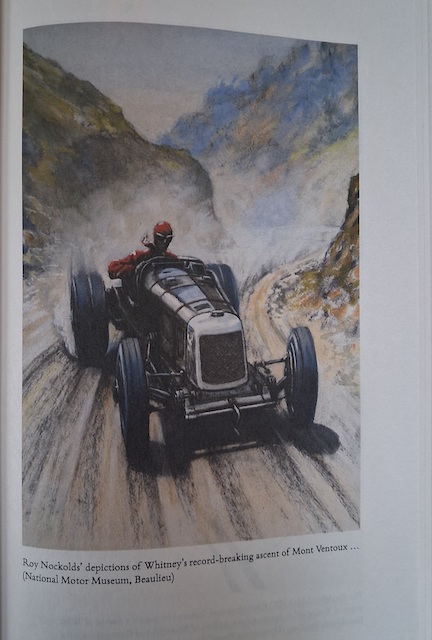

I grew up reading Motor Sport magazine, back when its long-serving editor Bill Boddy shared his rosy-tinted memories of Brooklands (always “The Track”) in almost every issue. But books like Kenny’s highlight what a dead end the famous banked track with its toytown “mountain circuit” was to become. Straight may have cut his racing teeth at Brooklands, and at the sweet but very short Shelsley Walsh, but he cemented his reputation at European venues such as the sixteen-mile Pescara circuit and the thirteen-mile gravel hill climb of Mont Ventoux (image below). About a third of the book is devoted to Straight the racer—less than some might expect, perhaps—but there is no lack of detail. As with the rest of this extraordinarily dense book, readers are well advised to pace themselves and savor the evocation of a wonderful era of motorsport, put into sharper focus by the gathering storm on the horizon. The illustrations are well chosen, depicting not only race cars and drivers and airplanes but also charming ephemera and sketches.

Race cars were Straight’s passion; boats became his amusement and fishing his hobby, but aviation was his destiny. While still in his twenties he owned a growing portfolio of airfields and small airlines and piloting was second nature. We learn how he once spent 83 hours at the helm of a De Havilland Rapide in only 13 days, making stops in various places and taking in a race in South Africa.

Race cars were Straight’s passion; boats became his amusement and fishing his hobby, but aviation was his destiny. While still in his twenties he owned a growing portfolio of airfields and small airlines and piloting was second nature. We learn how he once spent 83 hours at the helm of a De Havilland Rapide in only 13 days, making stops in various places and taking in a race in South Africa.

“Cometh the hour, cometh the man” are words often applied to Winston Churchill, but they applied to Whitney Straight too. The Second World War broke countless men—and women—but it was the making of Straight. First in combat as a fighter pilot, then prisoner of war, and then as a formidable master of logistics. The man who had started his war as a Pilot Officer ended it as an Air Commodore mixing (like his fictional counterpart Mountstuart) with the dramatis personae we’ve all heard of. Straight met everyone from FDR, Marshal Tito and Churchill to Ian Fleming, Airey Neave [2] and Soviet spy Guy Burgess. There’s plenty of tales of dogfights and derring-do, but also many insights into the vast complexity of making a nation’s war machinery work, and who better than the man already en route to becoming a master of industry before the war had even begun?

Straight ascended ever higher in the commercial firmament of the postwar era. The author doesn’t spare the detail of his subject’s boardroom warfare as BOAC boss, as well as how Straight weathered the storms caused by the De Havilland Comet’s catastrophic failures, Stratocruiser crashes, and much more besides. Including Rolls-Royce and its saga of boom, bust, nationalisation and sell off, then the Post Office and even the Midland Bank. The reader is left wondering if Straight ever slept, and if he did, what did he dream of?

There are clues, and Kenny’s analysis of Straight’s character is piercing. He describes a man who had “an inability to form male friendships – only Dick Seaman, Max Aitken and Hugh Casson penetrated the wall he formed around himself, and he lost Dick before he was 27.” Consider who these men were: Aitken, 2nd Baron Beaverbrook, was a newspaper owner and Conservative politician, while Casson was a British architect, designer, and writer. Now ask yourself whether confining oneself to a tiny circle of male friendships with men like these is desirable or even healthy. Was it perhaps the legacy of losing a father in childhood? Next, consider Straight’s relationships (plural, in spades) with women. A long and loving marriage to Daphne somehow co-existed with a succession of affairs, often with Daphne’s knowledge, if not tacit assent. These weren’t grubby one-night stands, but what appeared to be loving and long-lasting relationships; his affair with Diana Barnato Walker, the first British woman to break the sound barrier, lasted for decades.

Straight showed empathy and compassion to his employees but could be dismissive of others, considering Ernest Bevin (Foreign Secretary in Clement Attlee’s government) “a good sergeant who will make a bad officer” (ouch). About his award of a CBE (Commander of the British Empire), he sneered that it was “a horrid little pink gong which is given to stooge group captains.” A complex man then, easier to admire than to like, and on the evidence of this tour de force of a biography, ultimately unknowable. But this book is Whitney Straigth’s legacy, and it deserves every praise.

- BOAC – British Overseas Air Corporation (aka “Better On A Camel”)

- Airey Neave was “Agent Saturday” in the British Secret Service, later a politician who was murdered by the IRA in 1979.

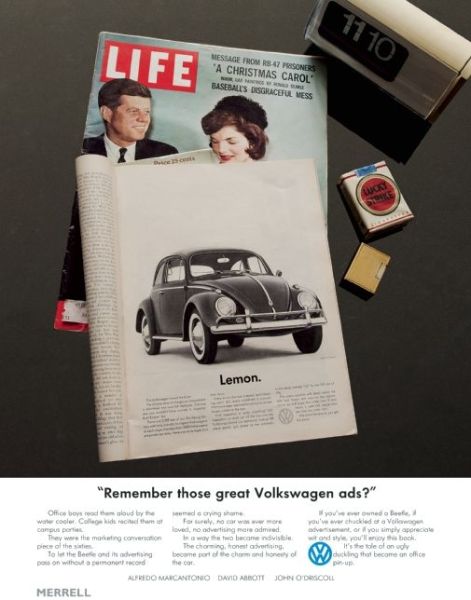

A nifty bookmark.

Copyright 2025, John Aston (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter