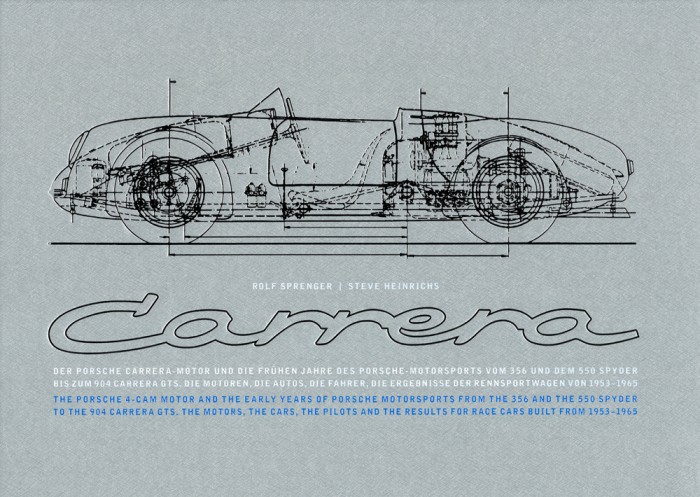

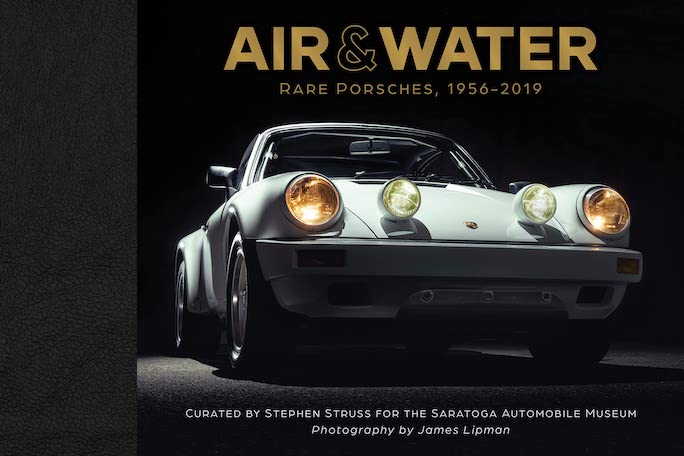

Porsche Carrera

The Porsche Carrera Motor and the Early Years of Porsche Motorsports

by Rolf Sprenger, Steve Heinrichs

“Our purpose with respect to this book has been to describe in detail the cars and motors, their background and their successes. In addition, we wanted to provide a fuller perspective on Ernst Fuhrmann, the designer of the famous motor.

Along the way, we have discovered more long-standing controversies than we thought existed.”

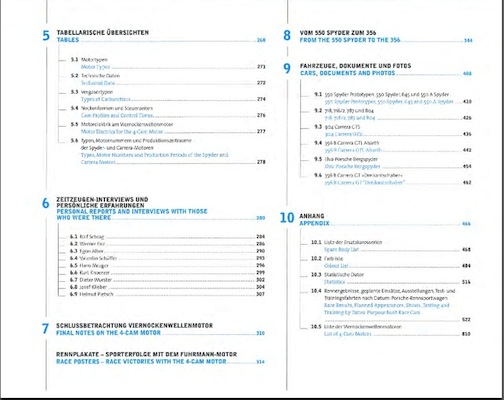

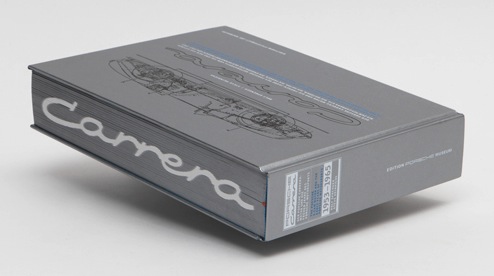

(German, English) The long subtitle above has an even longer sub-subtitle: From the 356 and the 550 Spyder to the 904 Carrera GTS. The Motors, the Cars, the Pilots and the Results for Race Cars built from 1953–1965. No wonder this turned into an 840-page opus, both, as the German press release so cleverly puts it, heavy [in weight] and hefty [in scope].

The controversies alluded to in the excerpt above are mostly of concern to people deeply entrenched in Porsche history and have mainly to do with chassis numbers and lack of comprehensive record keeping in the day, a common shortcoming. Even without such highly specialized interests, this book will be meaningful to anyone dealing with engineering matters and motorsports history.

That Porsche was able to establish competence and then dominance in the motorsports arena is in no small measure due to engineer Fuhrmann (b. 1918). Already his 1950 university thesis dealt with the merits of cam drive in high-speed engines, and it is his 4-cam used on those 1953–64 cars that had racing motors (i.e. not the early 356s that, while often used in racing, did not) that is the unifying thread in this book. That thesis, incidentally, is actually reproduced here, along with two related 1955 and ’56 patents. They are shown without any/much accompanying comment and thus mainly have value to people who can decipher formulae and graphs.

That Porsche was able to establish competence and then dominance in the motorsports arena is in no small measure due to engineer Fuhrmann (b. 1918). Already his 1950 university thesis dealt with the merits of cam drive in high-speed engines, and it is his 4-cam used on those 1953–64 cars that had racing motors (i.e. not the early 356s that, while often used in racing, did not) that is the unifying thread in this book. That thesis, incidentally, is actually reproduced here, along with two related 1955 and ’56 patents. They are shown without any/much accompanying comment and thus mainly have value to people who can decipher formulae and graphs.

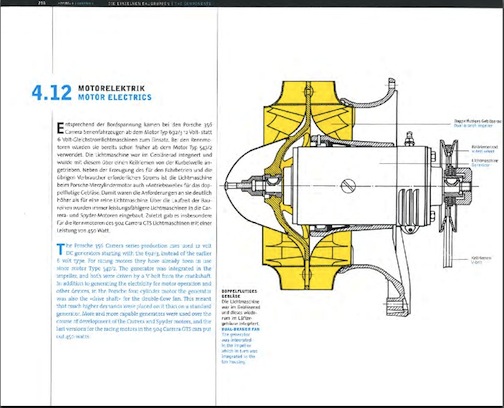

To set the scene, Porsche Archive chief Dieter Landenberger wrote a very nice Prolog emphasizing the firm’s early and lasting commitment to honing its engineering abilities by subjecting them to the stresses of racing. This is followed by lengthy appraisals of Fuhrmann and then the operating principles of engine types 547, 692, 887, and 719. Mechanically complex and therefore expensive (and difficult to find parts for) the 4-cam was also light and compact, its short stroke minimized wear, and little internal friction meant little waste of power. And while the 4-cam was phased out in favor of 8-cylinder racing engines, a key bit of technology—the vertical shaft valve drive—soldiered on.

To set the scene, Porsche Archive chief Dieter Landenberger wrote a very nice Prolog emphasizing the firm’s early and lasting commitment to honing its engineering abilities by subjecting them to the stresses of racing. This is followed by lengthy appraisals of Fuhrmann and then the operating principles of engine types 547, 692, 887, and 719. Mechanically complex and therefore expensive (and difficult to find parts for) the 4-cam was also light and compact, its short stroke minimized wear, and little internal friction meant little waste of power. And while the 4-cam was phased out in favor of 8-cylinder racing engines, a key bit of technology—the vertical shaft valve drive—soldiered on.

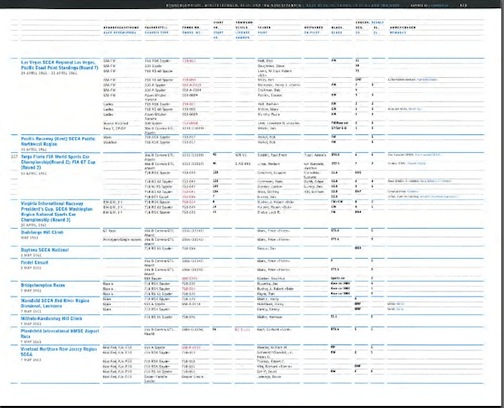

Sixteen individual components or assemblies are then presented in detail, followed by an assortment of engine specs and stats. Here and throughout, despite the fairly intense focus on engineering bits the text remains readable enough not to frustrate the general-interest reader. However, consumers of the English version will probably curse the person who thought putting light blue type on white paper was a good idea. And all but the youngest of eyes will struggle with the microscopically small type (2 pts?)  in the Notes column of the 60-page section of the book that is its greatest contribution to the record, a first-ever attempt at a comprehensive list of the 1545 cars with the motors in question, plus another 11 that were not strictly erected to that spec. Plenty of caveats apply to this section (some 10 data points each, meaning 16,000 items at your fingertips) and pickers of nits had better internalize them before complaining!

in the Notes column of the 60-page section of the book that is its greatest contribution to the record, a first-ever attempt at a comprehensive list of the 1545 cars with the motors in question, plus another 11 that were not strictly erected to that spec. Plenty of caveats apply to this section (some 10 data points each, meaning 16,000 items at your fingertips) and pickers of nits had better internalize them before complaining!

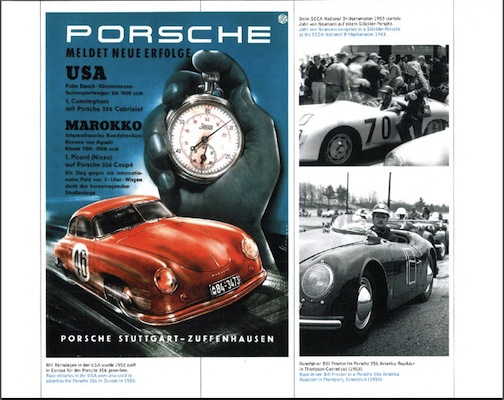

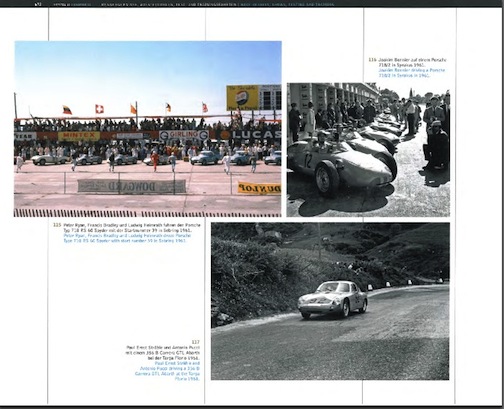

Nine interviews with folks who were there along with closing thoughts on the 4-cam conclude the narrative before 56 race posters (mostly undated but in chronological order) transition into a mainly photographic treatment of specific cars.

Consider that the book has almost 350 pages of Appendices (spare bodies, paint colors, statistics, 280 pages of some 14,000 race results 1953–1978, engine list) to appreciate that this is a reference-level resource and not a one-time cover to cover read. But it is that very bounty that necessitates a critical remark: if this book were a car, its physical construction would be deemed woefully inadequate for the intended use, a total disregard of function in favor of form. The 10 lb book is simply too heavy as a single volume and, moreover, the landscape format compromises the structural integrity of the spine/binding, causing the book block to sag which stresses the hinges and abrades the bottom front edge. Even in our bibliophile hands, after only a few weeks of intense but considerate use the review copy is seriously limp which is truly a shame for such an otherwise towering achievement.

Authors Sprenger and Heinrichs spent seven years on this book, the former a long-time Porsche engineer who joined in 1967 and the latter a historian with a legendary Speedster collection and well-known on the Porsche scene as the mastermind behind such seminal events as the 2004 Speedster anniversary and The Porsche Race Car Classic. Despite these unassailable credentials, the authors repeatedly sprinkle their text with caveats as to reliability or certainty of the data.

If you didn’t already think so before reading the book you will end up concurring with Landenberger’s remark that the “design of this power plant would become one of the most thrilling chapters in Porsche history.” And this much book for this little money too is thrilling.

If you have the 917 book, and how could you not, this book is similarly designed (except for the dustjacket, i.e. there is none); side by side they look positively intimidating to anyone who takes the measure of your bookcases.

If you have the 917 book, and how could you not, this book is similarly designed (except for the dustjacket, i.e. there is none); side by side they look positively intimidating to anyone who takes the measure of your bookcases.

Copyright 2015, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter