The Victorian Steam Locomotive: Its Design and Development 1804–1879

“. . . but the sight of a complicated and apparently cumbrous machine, moving itself under the mere direction of a human driver, forcibly overcoming not only its own inertia, but that of the many heavy carriages and trucks which helplessly follow its chains, is a demonstration of mechanical agency which, however often it may be witnessed, arrests the attention in every instance, and leads the mind to contemplate the means employed, or to inquire what those means are.

Let us become such inquirers, and endeavour to ascertain those means.”

If it weren’t for the old-timey flowery prose one could completely forget that this book was written over a hundred-thirty years ago!

It is a phenomenal shame that the person introducing the book, Pete Waterman, or for that matter the publisher are not making the historic significance of this book clear, merely calling it a “contemporary volume” and a “lost publication.” Nor is anything biographical said about any of the names on the cover. Why bother reprinting a book without giving today’s reader a reason to care??

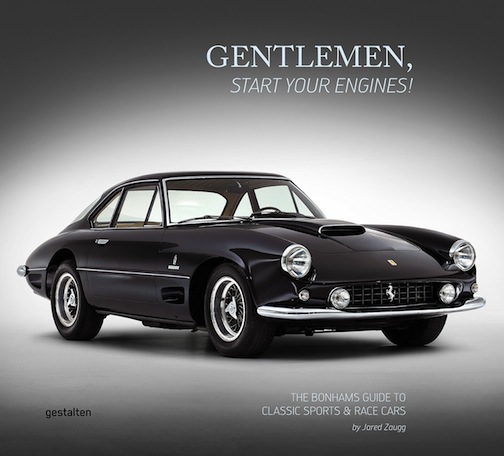

While nothing is said about why this text was “lost” or why it is being reissued in 2015, it so happened that the publication of the book coincided with an October 2015 Bonhams auction (at the Simeone Foundation Automotive Museum) of “Historic Locomotives of National Importance” belonging to the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago. This book, then, would be an ideal primer for brushing up on first principles of steam locos. Moreover, the book is British, and the first and probably most important of the five machines in the auction is an entirely original survivor of a British-built locomotive from 1834, the Mississippi believed to be the first locomotive in the American South.

Considering when and by/for whom this book was written—people to whom haulage by steam was an utterly novel concept—one of the great advantages to the modern reader is that the book does not presume the reader to know anything. The first of the two parts the book is divided into is a deliberately slow, thorough introduction to the fundamentals of this form of locomotion. Steam and especially railroad historians may deduce from the year of first publication, 1879, that it had to have been published posthumously because Dempsey (b. 1815) had died, young, in 1859, in India where he was architectural engineer of the Great Indian Peninsula Railway and Vice-President of the Bombay Mechanics Institute. This is where the second author name comes in: Daniel Kinnear Clark (1822–1896), a near contemporary to Dempsey but with the good fortune to live rather longer. He too was a railway engineer, had in fact been Locomotive Superintendent at the Great North of Scotland Railway 1853–55, and wrote comprehensive books of his own on railway engineering matters. It is he who ably condensed Dempsey’s voluminous manuscript into the present book.

While Dempsey had published in 1847 the well-received Practical Railway Engineer, he is most remembered for his guides on the construction of railways, docks, drainage, iron bridges, and roofs. In his Rudimentary Treatise on the Locomotive Engine in All Its Phases (1855) he had written “We may now commit ourselves to the express train, at forty miles per hour, with infinitely far less risk of a broken neck than we could forty years ago.” Forty miles, perish the thought.

Dempsey looks in fact further back, to James Watts and the first locomotive patent in 1759. He describes the operating principles of steam apparatus, distinguishing between stationary and “portable” machines, and explains all the moving bits on a locomotive as if he were talking to someone standing with him on a platform marveling at that hissing, spitting monster. This part does that, this here connects to that, this is how large it is and what it’s made of. What could be easier to follow?! Yes, there are technical drawings and new jargon to absorb—but now you know why a man-hole is different from a mud-hole or how to clean a boiler or how gauges are made steam-tight (yet another use for hemp!).

After fifty-odd pages at this leisurely pace, Part II, “The Modern Locomotive,” offers 23 intense chapters that require focus and attention. In parts, some physics knowledge will come in handy too so as to appreciate the physical forces acting on a locomotive, such as, for instance, the weight of the actual train itself but also how the topography of curves and hills, and even wind force throw up variables.

There are obviously no period photos but the oldest of the ca. 40 photos dates to the early 1900s. All this is most fascinating, engagingly presented, and at the end you’ll be pretty much as educated about steam locos as your Victorian forebear would have been. There are even some blank pages at the back—perhaps to scribble your own formulas.

As to Waterman and that Foreword, why him? Fresh out of school he went to work for British Railways, becoming a steam locomotive fireman in the 1960s and rose to become a big name in the UK rail industry. But it is the millions he made in between these stints as a music producer-songwriter (500+ million records), auteur, and TV personality that bankroll his private collection of steam and diesel locos (now organized as the Waterman Railway Heritage Trust) and his model railway business (cleverly named Just Like the Real Thing). Just a few months before this book came out he sold 32 scratch-built model trains from his collection—for a cool £627,229. He knows his trains, in other words.

Copyright 2015, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter