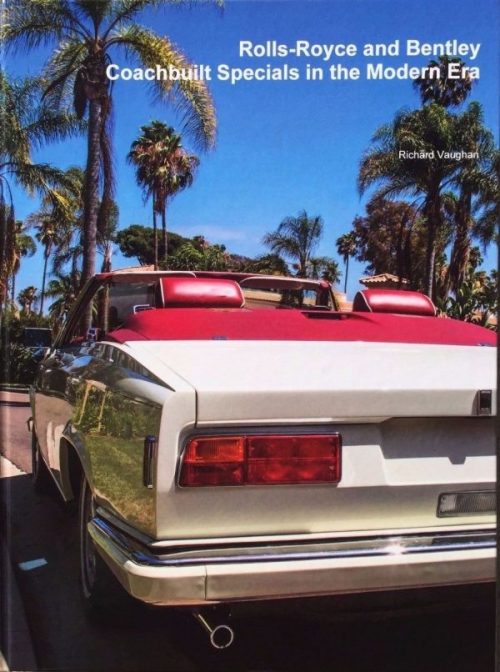

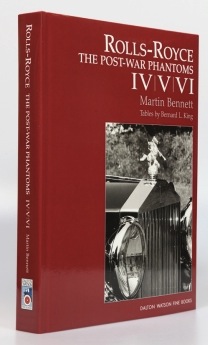

Rolls-Royce and Bentley, Coachbuilt Specials in the Modern Era

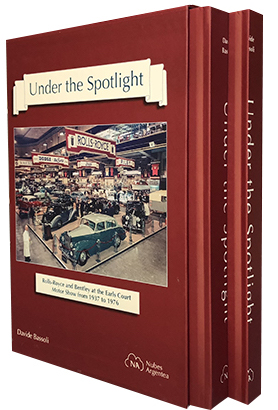

The subject, modern coachbuilt Rolls-Royce and Bentley cars, may seem, to the general automotive buff, a rather constricted niche, one of limited rather than universal interest. And it is—thus perhaps limiting the number of car folk willing to spend $115 to own this book. Which is unfortunate. The amount of time, research, and labor that the author has undoubtedly expended here will never be fully or fairly compensated. But books such as these are not made by those seeking wealth in publishing. They arise from a deep-seated interest in and appreciation for the subject at hand, grow from a compulsion to find as much information as possible. They happen because the author is all but forced to go ahead and get the job done.

For those not steeped in Rolls-Royce lore, some background may be helpful to understand the significance of this book. In 1931 Rolls-Royce Motors purchased Bentley Motors. After WWII, Rolls-Royce and Bentley motorcars were built side by side in Crewe, England—many of the Bentleys for many years being fairly identical sister cars of their Rolls-Royce counterparts. Think of the Ford Crown Victoria and the Mercury Marquis. In 1998, the two marques were split. Volkswagen acquired the Bentley name and the factory at Crewe, while BMW acquired the Rolls-Royce brand, eventually producing new models in their new facility in Goodwood, England. That is why, in Rolls-Royce literature, the two marques are most often examined in tandem.

The Modern Era is a specific designation in Rolls-Royce scholarship. It refers to the fact that up until 1965, the introduction of the Rolls-Royce Silver Shadow, Rolls-Royce cars were of body-on-frame construction. This type of manufacture made it relatively easy for coachbuilders to ply their trade, and made for a goodly number of one-offs and small batches of similar if not identical models. It has been said that the Silver Cloud (1955–1965), along with the accompanying Phantoms V and VI, were the last of the true coachbuilt cars (even recognizing that the Silver Cloud, and her sister car, the Bentley S, were very popular wearing factory standard steel saloon bodywork), the end of an era, an end to very old and very traditional ways of constructing bodies and interiors and erecting these on a rigid frame. The Silver Shadow, the first series of the Modern Era, is of monocoque (unibody) construction. Vaughan explains this, and then goes on to discuss the newer methods of coachbuilding—methods involving the various ways of solving the problems inherent in monocoque motorcars where the body of the car itself is integral to the car’s structure. And as if cyclical, the current series of Rolls-Royce cars are built with space-frame construction, affording, in essence, the same ease of coachbuilding as the older body-on-frame cars. But, as Vaughan points out, modern craftsmen offering modern coachbuilt cars must contend with ways to subvert the various safety testing and certification found throughout the major world markets.

What is surprising is the large number of cars the author has tracked down. Just imagine the networking among enthusiasts, photographs and information pouring in from throughout the world, and imagine the task of sorting all of this in a meaningful way. Usually books on coachbuilding are arranged by coachbuilders—all the Hoopers in one chapter, etc. Here we have the cars arranged mainly by type: Silver Shadow coupes, Camargues, Silver Spirit wagons, funeral cars and the rest. This method has its merits, but it would hamper future historians researching the work of a particular coachbuilder.

Scale models of the cars are also shown throughout the book—a nice accompaniment.

The chapters concerning the cars purchased by the Brunei Royal Family are exceptional because of the large number of photographs Vaughan has managed to amass. Over the years the motorcars of the Brunei Royal Family had become legendary among Rolls-Royce enthusiasts. It was known that hundreds of cars were purchased each year, one-offs and small batches, from Crewe—and involving various coachbuilders worldwide. It has been said that these purchases actually kept the company afloat during the 1990s. What was largely unknown was what these cars looked like—so, again, the number of photographs assembled here will certainly be valued. A brief history of the royal family, their connections with Rolls-Royce, and their incredible car collection is given. These chapters alone would be sufficient reason to order Coachbuilt Specials.

We found the layout and overall aesthetics to be attractive if not stunning. It is counterintuitive, but the tactile quality of the pages themselves in the softbound book is much better than that of the hardbound editions. This had to do with the economic quirks of publishing a book like this. And a word must be said of the photographs. Many are of high quality, but, because of the nature of the book, just as many are substandard. But this not to criticize: These cars are rare and seldom seen, and often photos were taken on the fly by amateurs. Vaughan is not unaware of the problem: “This is not a situation where we have access to great quality pictures of every car. In some cases, the pictures are only 72 dpi, which is quite a bit less than the 300 dpi (minimum) needed for print. I’ve decided that a grainy picture is better than no picture. Frankly, the majority of the worst pictures were never supposed to be seen by anyone. Some of them are pictures of pictures of photocopies of pictures.” Because of the book’s purpose, this in no way detracts from its merits. This admixture actually adds to its personality and charm.

Vaughan considers his book more of a “coffee-table” book than a “reference tome.” At first we demurred. A book like this would immediately be taken up by Rolls-Royce scholars and enthusiasts who have a taste for completion, a desire to know of every car, perhaps an addiction to lists of chassis numbers and other esoterica. But wait—where are the chassis numbers? Where is the index? So the answer oddly falls somehow between an entertainment and a reference. The general reader will enjoy the images—but it is not inconceivable that, somewhere down the line, scholars will use this book as a starting point, a sourcebook for further research. And this is quite okay. More than okay. Coachbuilt Specials will be more and more appreciated as time goes by.

A brief disclaimer: I have supplied photographs for this book and have corresponded with Richard Vaughan.

Copyright 2017, Bill Wolf (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter