Alpine: The Quest For Absolute Agility

The arrowed A logo in the top left is not actually printed on the cover but a sticker on the cellophane wrap.

by Gilles Uzan and Jean-Luc Fournier

“That’s when she feels hands, on her hips, slipped beneath her jacket, beneath her sweater. She has no idea how he did that, she heard nothing, he’d moved as magically as the rest of that night, but those hands turn her around very gently, and pull her against the chilled leather of his jacket.

She feels his warm lips upon her face, and something erupting in her heart. And there, just behind them, the Alpine’s headlights focused upon her, like fiery eyes.”

Order! Order!

Normally we start our reviews with an excerpt that is indicative of the author’s voice or says something archly relevant about the book. And in its own way, the excerpt we chose this time does too. It is from the end of the novella Alpine by Monica Sabolo that is included as a separate booklet. Wait, a novella?

Well, on the “fun with books” scale this book is as off the charts as the original Alpine was, and the new Alpine is on the “fun with cars” scale. In his recently published memoir David Twohig, who was chief vehicle engineer on the [new] Alpine project, writes about the original car that it had an incalculable effect on the French psyche, and he describes Alpine as “a strange little brand—it inspires passion, nostalgia, very strong opinions—and oceans of ink.” The ink refers to the large body of literature on this car, at least in French. In English, Roy Smith’s excellent Alpine Renault published in 2013 remains the go-to book, and it ended with a cliffhanger: “While this book was in preparation, a story broke that should be mentioned. The news was that Renault and the English sports car company Caterham have joined forces to resurrect the name Alpine and create a sports car for a new era.” And that new car is what this new book is all about.

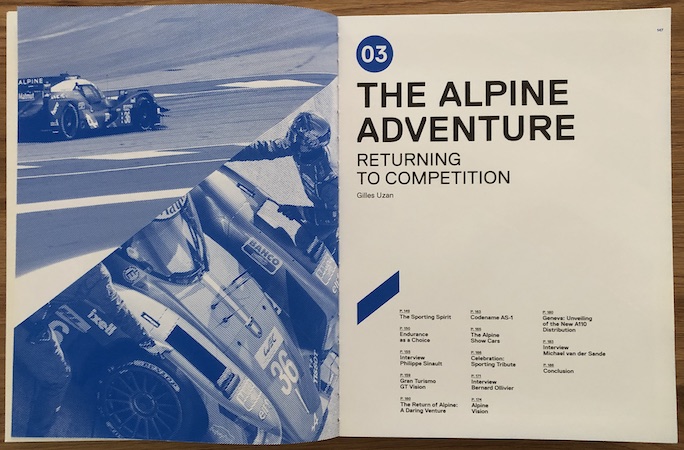

If the excerpt we used above is too frivolous for you, how about this one, by Alpine Managing Director Michael van der Sande: “In this book, we share in words and pictures the extraordinary experience that we lived within the Alpine team these past few years—how the new A110 was conceived; why we decided to relaunch Alpine as a separate brand; and how motor racing is a fundamental part of the Alpine story.” That’s exactly what this book does, and while it relates quite a bit of 1960/70s Alpine history, the Smith book is a highly recommended companion read for deep background. As is Twohig’s, for a different reason we shall get to.

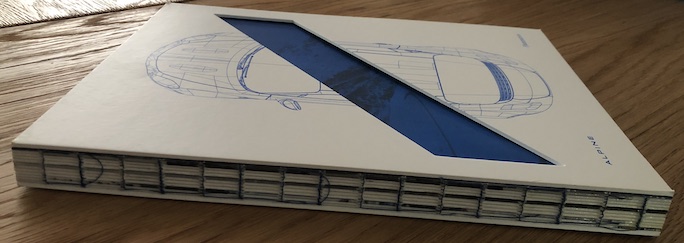

Before delving into the book’s content, a few words about its form: no spine as such (the glued-up signatures are left exposed; the thread is blue, surely a nod to Alpine’s signature color), the covers are hard board but have no protruding edges, the blue slash on the front cover is not printed but cut out. The clue is in the section “The Battle for Lightness” (remember the Caterham connection!): “Anything that was not essential was removed.” So, a tip of the hat to the cleverness of the book designers (ABM Studio, Paris) who so completely synched the book’s form to the book’s topic!

And another word about that novella (see below). Its pagination starts with 83 and ends with 95—and those are the very pages that are “missing” from the main book, meaning the book designers who could have done anything they wanted with the booklet must be signaling that it should be read at this very point in the big book.

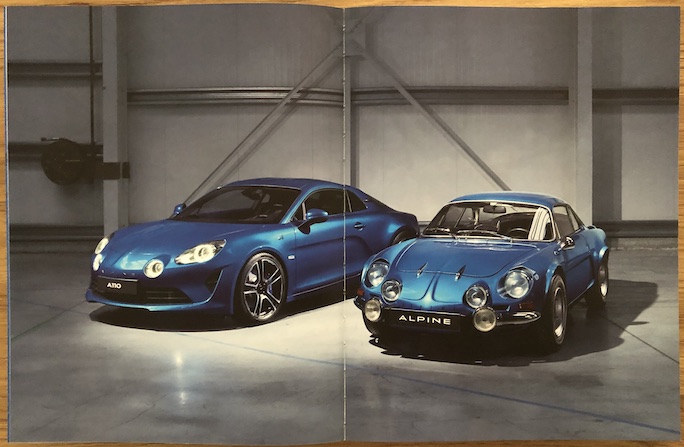

Not all the pages in the book are numbered, which is entirely common with full-bleed illustrations or here a crossover spread. The inattentive reader might totally miss the fact that, in the case of the spread shown, the page preceding the verso is 79 and the one following the recto is 98. The diagonal blue stripe is another clue that something intentional is going on here. Also, it matches the stripe on the booklet’s cover. And once you read the novella, even the photo no longer looks random.

Books by, or commissioned by automakers are often a mixed bag inasmuch as they provide the author unlimited access to material outsiders may not be privy to but they can easily turn into brazen puff pieces. This book really does not have a whiff of the latter; that it strikes a wholly sympathetic tone is simply because the car and the overarching philosophy and especially the entire process of making it are praiseworthy. Although . . . there is something that one can only call “sanitizing”—the 50:50 partnership with Caterham without which Renault would not have greenlighted the Alpine project. The Twohig interview is the first spot the book even alludes to it, well, has to allude to it since it was its dissolution that prompted his appointment in the first place. But it is only in his own book, written a few years after this one, that he lets on how far off the rails Caterham had gone. One should not fault this book for “staying on message” but the take-away is that an astute reader must always be mindful of who is in the driver’s seat of a story.

The book is an homage, in so many words. Authors Uzan and Fournier are seasoned automotive journalists, Fournier here penning the historical sections (which, to single them out, are printed on different paper stock). Uzan comes from the photography and art direction side and if you’ve seen the biannual automobile culture magazine Garagisme he started in 2012 you’ll recognize his tone and “take.”

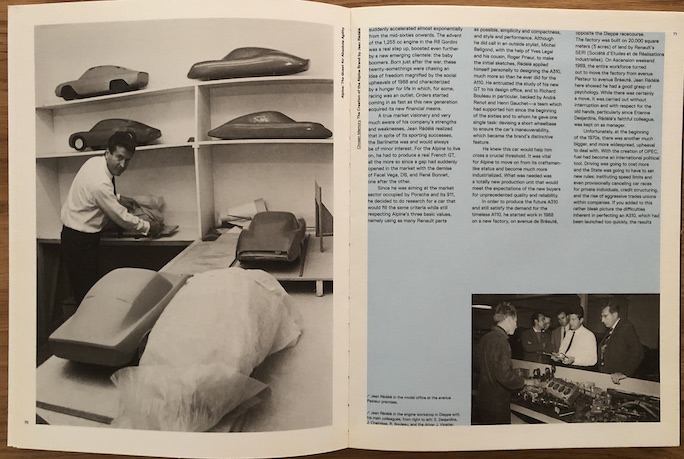

Alpine chief Jean Rédélé had been a brilliant rally driver and was a gifted leader of men. His son is the keeper of the Alpine Car Collection which the team visited early on for a full-immersion session.

Readers in the auto industry will appreciate the Alpine story as rather unique. Dusting off a storied brand is in and of itself nothing new but going the extra mile to set it up as a separate entity (i.e. a wholly-owned subsidiary of Renault; the other side of the coin being that if it fails it’s easier to manage the reputational fallout) and starting with a completely clean slate—hiring staff, setting up a design studio and manufacturing space etc.—and giving the team the brief to create the “complete Alpine experience”—from the car itself to the stationery to showroom design to marketing—is truly uncommon. All this is covered here, told by the people who were/are there. In fact, even people who were involved with the original Alpine played a role, not least in “decoding the Alpine style” for the enlightenment of the brand’s new interpreters.

The book was published simultaneously in French as Alpine. La quête de l’agilité absolue (ISBN 9782081399419).

The Alpine A110 is not for sale in the US (if it were it would be a $70K–100K car) but you could have witnessed its US unveil at the inaugural Grand Prix of Miami in 2022 to which it accompanied the Alpine Formula 1 team, sporting a special livery called the South Beach Colorway package.

Describing New York artist Penelope Umbrico’s unusual work and MO (installations, video, digital media) would require a lengthy treatise. Alpine, who says they “recognized a kindred spirit,” commissioned her to reimagine her work of digitally transforming images of “Mountains, Motion, Light and Speed.” It is printed here on special, glossy/varnished paper as a stand-alone half signature, another unusual touch in an all-around unusual book.

Copyright 2022, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter