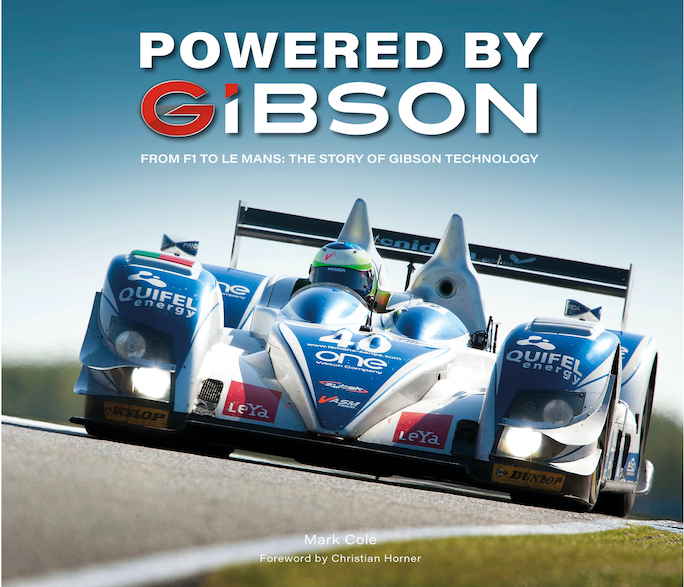

Powered by Gibson—From F1 to Le Mans

The Story of Gibson Technology

by Mark Cole

“If Barnes Wallis of Dambusters fame hadn’t already existed, Dr Bill Gibson would have fitted the role perfectly.”

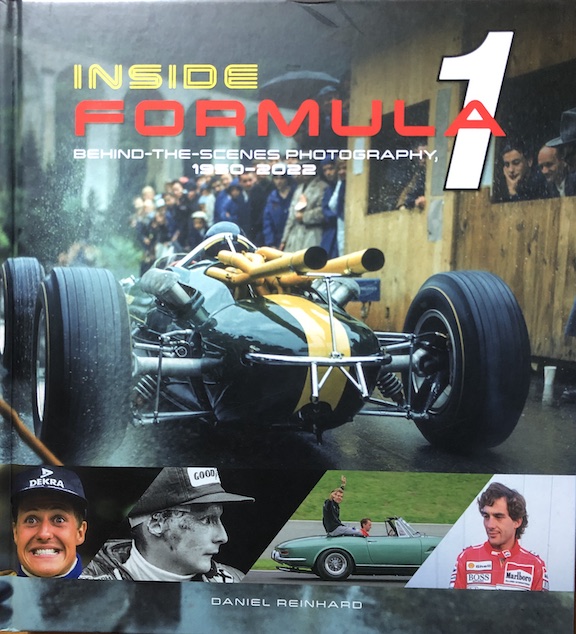

Engines were important when I was a motor racing obsessed kid in the 1960s. Old boys were still waxing lyrical over the howl of the BRM V16, while I was almost hyperventilating over the operatic scream of the Matra V12. But fifty years later, we take engines for granted, while elevating chassis designers and aerodynamicists to superstar status. It’s a shame, but it’s understandable too, and here’s why. First, engines are no longer visible—unlike the V12 with the bunch of bananas exhaust of the 1968 Ferrari 312. Second, they don’t blow up very often—unlike the operatic demise of mid-80s F1 turbos, boosted to oblivion. Third, engines have become so efficient they rarely sound good—unlike the symphony of howls, bangs, and seismic rumbles from the RVX V-10 in Toyota’s 2006 F1 car. Fourth, power is often restricted by Balance of Performance rules—unlike the free-for-all of 1980s Formula 1. And last, engines are so damn complex that we don’t even call them engines anymore, but “power units” with both MGU-H and MGU-K—so not very much like a Cosworth MAE.

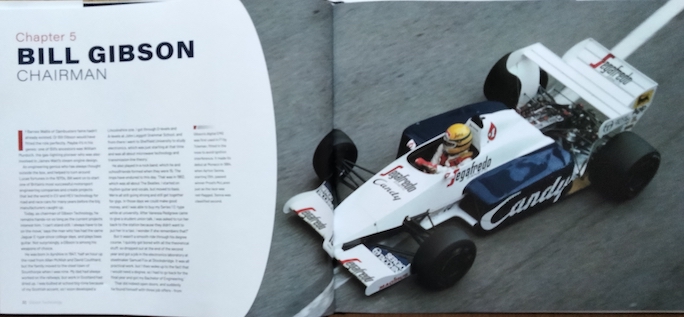

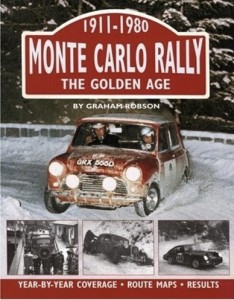

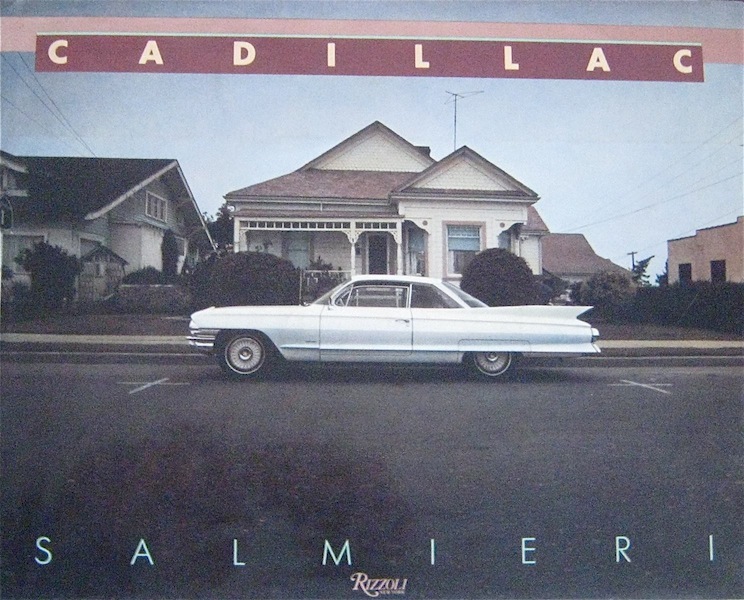

Ayrton Senna at Monaco in the 1984 Toleman which featured Gibson’s digital EMS.

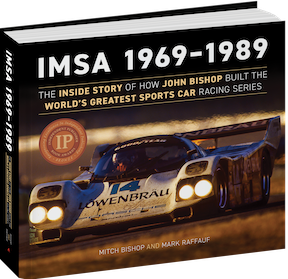

Forgive the long preamble, but it is important to understand the significance of this elegantly produced book from Porter Press. Powered by Gibson is the long and often complicated story of the company whose engines have been winning races for decades, first as Zytek and latterly as (primarily) LMP-2 engine supplier Gibson. Mark Cole is well placed to write this history, given his long immersion in sports car racing, including no fewer than 45 years of media work at Le Mans. And we need an expert guide, because the history of sports car and endurance racing is fiendishly complicated, with a cycle of boom and bust against a rules framework of Byzantine complexity. That is why, unless you know as much as Mark Cole does, I recommend that you start the book by reading Appendix 1 “The Rise of Sportscar Racing.”

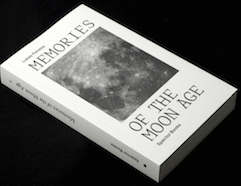

The book’s rear cover, with a piston from the A1GP car given to me by Ian Lovett , whom I mention in the text.

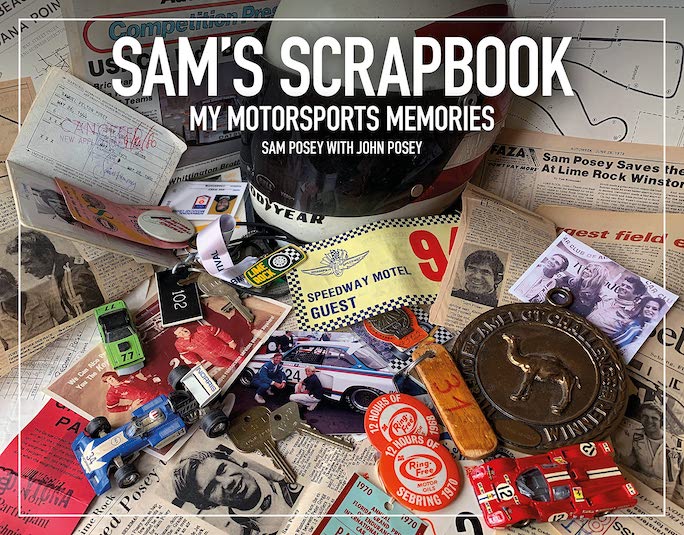

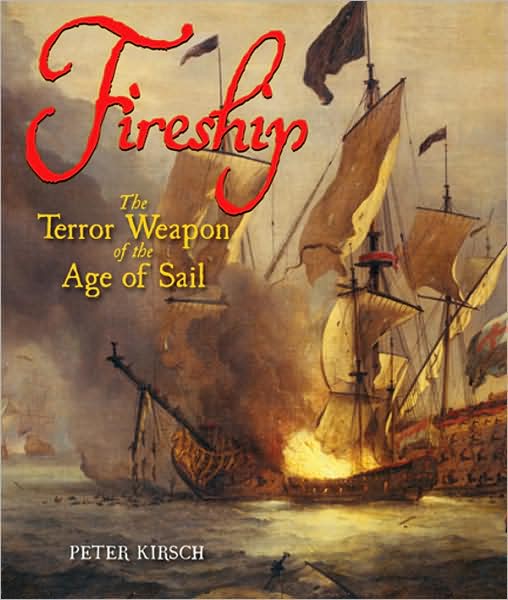

The book is in landscape format, enabling the 150 images, primarily but far from exclusively of Gibson/Zytek-powered sports cars, to be displayed to their full and colorful effect. The 11 chapters include interviews/biographies of four key men in the Gibson story—John Manchester, Trevor Foster, Tim Holloway, and founder Bill Gibson. Another chapter contains interviews with other personnel, including R & D chief engineer Yutaka Hiawari and technical director Ian Lovett, to whom I sold my first Caterham Seven back in 2008. Scotland has always punched above its weight in motor sport and Ayrshire-born Bill Gibson is described as “an engineering genius who always thought outside the box.” After turning Lucas fortunes around by improving its fuel injection systems, Gibson has enjoyed a stellar career in his own right, punctuated by early success with digital EMS with the Toleman F1 team, then sole provider of F3000 V8s for nine years and, of course, extraordinary success in LMP2 (215 wins) and even LMP1 (5 wins).

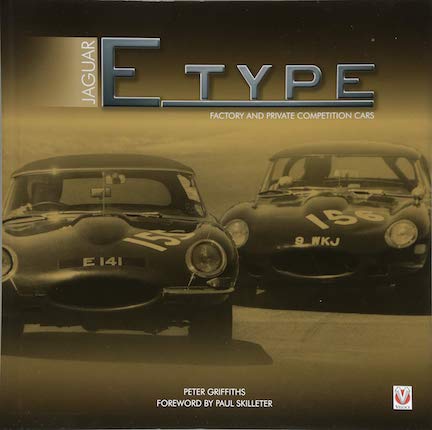

It’s very easy to warm to Bill Gibson. There is something endearing about a man who still drives the E-Type Jaguar he bought while still at a college when most students at English universities might aspire to nothing more exotic than an ex-Post Office Morris Minor van. And Gibson is still playing bass guitar in The Imps, the band he formed with school friends in 1962. That made me smile.

This is a book whose modest 128 pages do not skimp the detail, and most of its content concentrates on the many different engines Gibson has created, both in its own right and for clients. There’s plenty of bedrock information on engines such as the LMP2 control engine, the 4.2L GK 428—and how many manufacturers of earlier eras, perhaps even a Cosworth or an Ilmor, could boast of not a single failure in the 60 engines it had leased out in a season? As commercial director James Hibbert puts it, “I like to think that teams know they can rely on us . . . to date the GK428 . . . has covered over four million kilometres.” Cole’s access to his subject has also made him privy to the economics of the engine supply deals. We learn that a GK 428 is lifed at 50 hours and the engines are leased out at 1,250 Euros per hour to customers. Not a bargain basement price but it puts the 2023 Formula 1 budget cap of $123 million into sharp perspective.

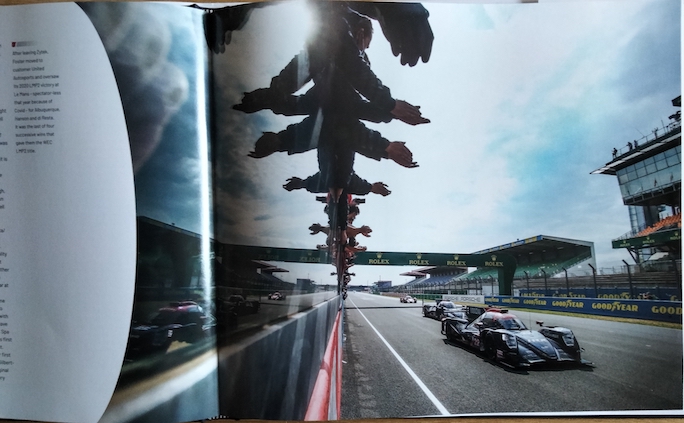

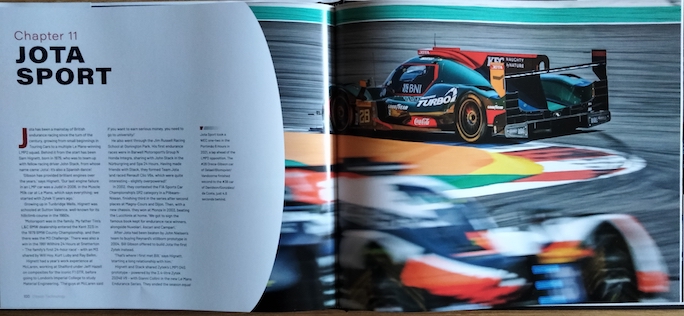

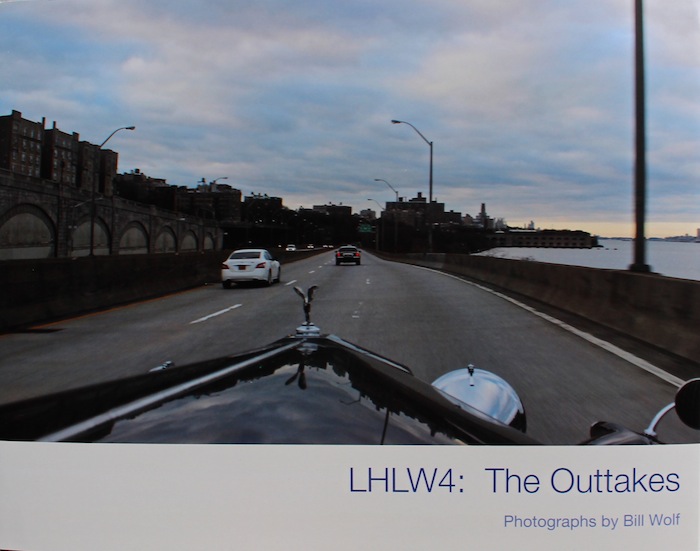

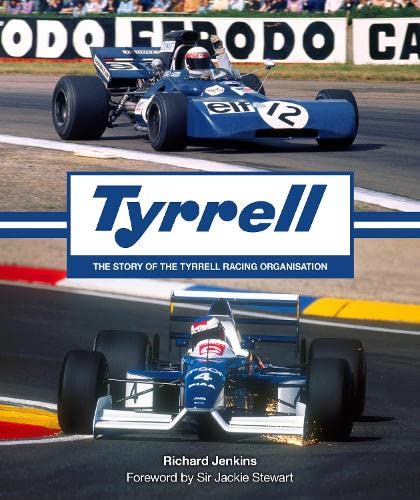

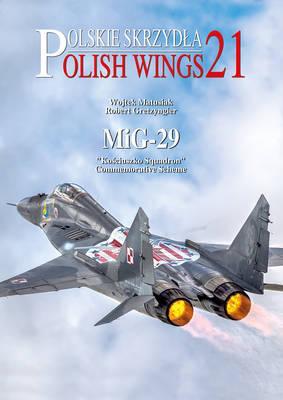

Oreca Gibson at Portimao 8 Hours , 2021, the second car in a Jota 1-2.

Although the Gibson story undoubtedly deserves to be told, the reader may form the opinion, as I did, that the book was commissioned and there is sometimes the whiff of the press release in the style and content. It isn’t a hagiography per se, but the tone is relentlessly upbeat and if there have been bumps in Gibson’s road to success, they are not dwelled upon. This is a book that needs to be read slowly and carefully, as Gibson’s story is entwined with so many other motorsport names, from United Autosports (McLaren boss Zak Brown’s joint project with Richard Dean) to Jota Sport, Reynard, Alan Smith Racing, Panoz and many more. It’s sometimes hard to keep up, especially as the same story is often related from the perspective of more than one person.

In an era of motorsport where engines are often taken for granted, this book highlights one company’s formidable record in making affordable, powerful, and reliable race engines. In a first for this reader, you can even download the QR code on page 113 and listen to what is described as “The Greatest Soundtrack in Motorsport.” Chacun a son gout—to my ears the sound of the GK428 reminded me of that pricey root canal surgery I had last year. I confess to preferring a Matra V12 or a BRM V16 for my aural delight, but that is where we came in, right?

Copyright John Aston, 2023 (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter