Building Engines for War

Air-Cooled Radial Aircraft Engine Production in Britain and America in World War II

by Edward M. Young

by Edward M. Young

“Aircraft and engine manufacturers could not accept the loose tolerances, low fuel efficiencies, and persistent breakdowns that were routine in vehicles . . . hence auto plant methods would not serve.”

—Philip Scranton, Rutgers University

Until this book, previously published histories leave readers with the impression that the transition to production of wartime materials was relatively seamless due to automakers already utilizing methods of mass production. While ultimately the automakers did succeed and even exceed expectations supplying the needed materials—especially aircraft with their ever-increasingly powerful engines and with Buick and Studebaker in particular held up as shining examples—it didn’t happen quite as easily as accounts would have you believe.

There are some telling/notable differences between mass producing engines for land-going vehicles and those that make their way through the air for the latter cannot tolerate the items enumerated in our opening quote. Then too, aircraft engine production “facilities had to be flexible, not fixed, so that design changes could be incorporated smoothly into assembly operations” as warranted by the “on-going search for greater power . . . greater reliability, reduced weight and improved production methods.”

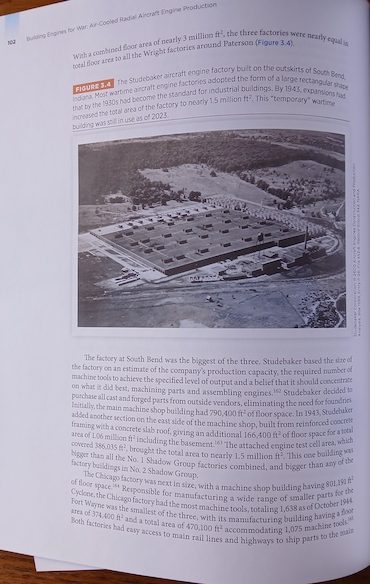

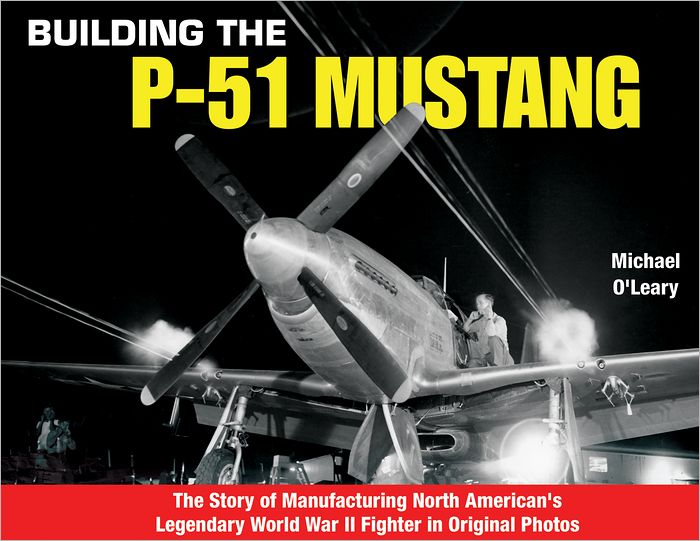

Studebaker’s purpose-built aircraft engine factory building in South Bend. As of 2023 this 1.5 million square foot “temporary” wartime building is still standing and still in use.

What began as Edward “Ted” Morris Young’s doctoral dissertation, he expanded into what is now this book once he’d earned his PhD in Military History from King’s College London in 2022. And a splendidly informative book it is too. So, thanks to SAE for making this work available to the larger, interested (and hopefully book purchasing) public.

The individual plant/manufacturing engineering challenges were real; process and production engineering alike. But so too were overarching governmental requirements for more: more airplanes, more weapons, more of everything in order to enable prevailing over the Axis powers. British industry felt it first due to proximity so first efforts involved the interface of Bristol with Austin, Vauxhall, Rover, Rolls-Royce and Daimler. Particularly helpful was Bristol’s own in-house developed “Bible” detailing down to the minutest specific every step from raw material to finished, running aircraft engines.

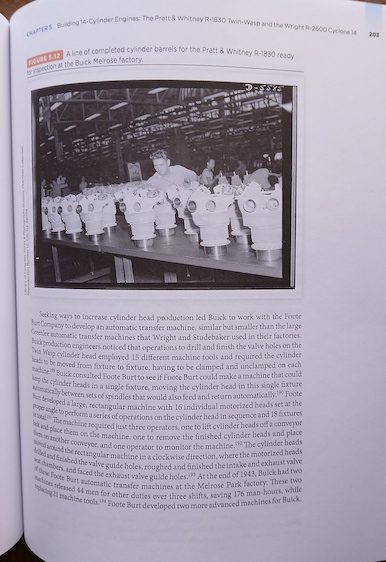

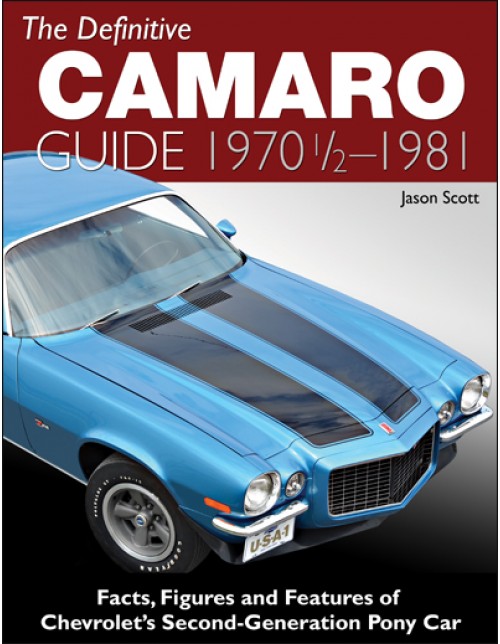

A line of completed cylinder barrels for Pratt & Whitney R-1830s ready to be inspected at the Buick Melrose, Illinois factory.

Once America was drawn in— even before Pearl Harbor—to augment what the UK could produce, American automakers were as well. Studebaker under Harold Vance established a separate division and erected purpose-built buildings, one in South Bend, one in Chicago, and one in Fort Wayne. Young takes his reader behind those closed doors and puts us in the shoes of the engineers and workers as they parallel their process and production engineering to those at Wright Aeronautical facilities to build Cyclone engines

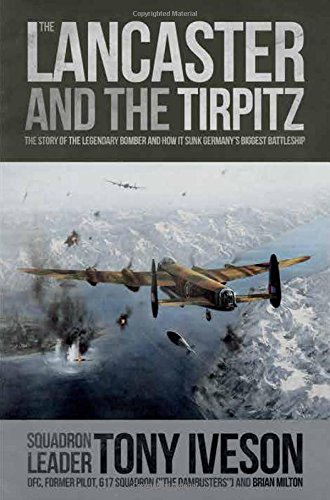

As war progressed with its need for bigger bombers, Young turns his attention back to the UK and the Air Ministry’s simultaneous need for engines with different capabilities noting that “It is unfortunate that official histories of wartime production make so little mention of the importance of production and process engineering, nor the British automotive, aircraft engine, and machine tool engineers who were responsible for this success.”

Turning his attention back to America, more manufacturers are quickly included ranging from Chevrolet and Buick to Chrysler and Dodge, then Mercury and Ford, as well as Nash and Packard, even International and Graham-Paige. Now, think back, if you will, for just a moment to that all-important opening quote for it alludes to an item of great concern to the aviation engineers: quality control.

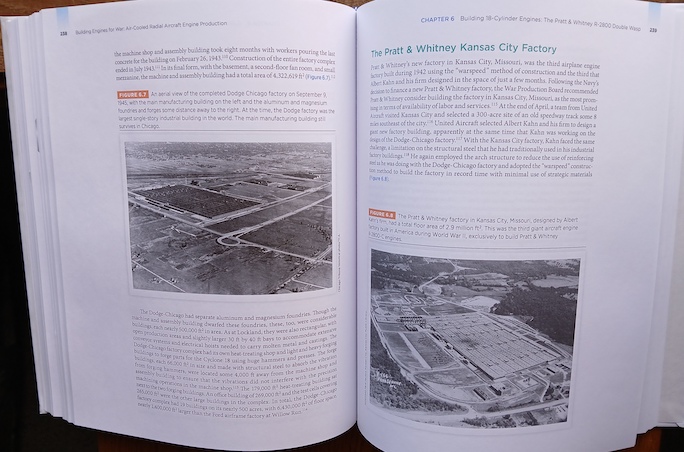

On left, another building constructed for wartime work, this for Dodge designed by Alfred Kahn. This 4,322,619 square foot building also survives today in Chicago. Right is the Pratt & Whitney factory, another Kahn design, to build exclusively R-2800-C engines was located on southeastern side of Kansas City, Missouri.

Consider, if a car or truck engine fails it is inconvenient but not as likely to be deadly as the aftermath of aircraft engine failure. One aviation engineer is cited saying “Our standards of quality and precision were not easily come by in the mass production industries.” Engines built to be installed on an aircraft had to pass rigorous tests. That said, one by one, the automotive engineers came to understand, support, and practice “the high demands for durability and dependability . . . sending hundreds of engineers and production experts to the Pratt & Whitney Hartford factory to learn.” And subsequently, working together, the auto and airplane engineers would even come up with additional improvements to production and reliability protocols and practices.

As mentioned already, SAE is to be commended for publishing this important book just as Ted Young is to be commended for expanding on his thesis for he has added a voice, a perspective, never presented with such clarity and detail before. It but remains to you, the curious and thinking reader, to obtain your own copy in order to read and be enlightened too.

Copyright 2025 Helen V Hutchings, SAH (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter