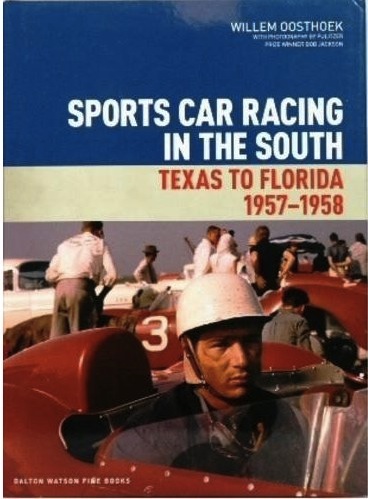

Inside the Paddock: Racing Car Transporters at Work

by David Cross with Bjørn Kjer

by David Cross with Bjørn Kjer

This is a wildly entertaining book that was simply begging to be done. It’s the sort of slap-your-forehead thing that makes you cry “Why didn’t I think of this?!” Fortunately David Cross had that epiphany. For people who only experience racing from the remove of their TV screen, paddock sights and sounds and smells may be utterly nonexistent but even they should wonder: how does a racecar get around when it’s not going around?

In the very olden days, a racecar was often enough driven to the track. The gasoline-powered car wasn’t ten years old when someone figured there was enough variety around to put different marques to the test: a race. The year of the first “real” race, Peugeot happened to make a van, and the next year Daimler produced the first purpose-built truck: enter, the support vehicle. Many of the early tests and races were endurance events so driving a competition car to the event was on the one hand a pretty good test right there. On the other hand, roads were bad, sometimes nonexistent. Also, spares and personnel had to be transported. Trucks were the answer, and especially after WW I easily available as surplus. In 1924, it was again Daimler, which always took racing serious, that offered (one of?) the first purpose-built race transporters—and nothing has been the same since.

Aside from the merely practical attributes the race transporter brought to the sport it also spawned a new nomadic lifestyle and pretty much from the beginning, tales of epic transporter journeys entered paddock lore. From dead tired crews half asphyxiated by gasoline fumes in drafty cabins driving the truck off the road, to bribing customs officials, some of the most colorful racing tales have nothing directly to do with the racing cars. The book barely alludes to any of the above. In fact, even after, make that especially after, repeated readings of the little text there is, one is tempted to remark that a sentence in the Introduction really paints too rosy a picture: “Transporters have been an integral part of motor racing history and one of the results of this book may be to encourage motorsport journalists to better inform their readers how racing cars arrived at the circuit in tip-top condition and on time.” Tip-top is certainly the desired condition, and nowadays the rule rather than the exception, but how entertaining a book would be that showed what all can and does go wrong with transporters.

Another remark that doesn’t quite strike the right tone is the Earl of March calling the book “definitive” in his Foreword. It is nothing of the kind—and the author is the first to say so. The good Earl of course means well and, as the host of the Goodwood FoS and Revival, has, as Cross says, “probably done more for historic motor sport than anyone.” He only has to look out the window during the Revival to see bunches of transporters parked right in his own yard—but those are as random as the ones in this book. This is by no means a shortcoming, just something to be clear about before you dole out $89.

There are many ways to slice and dice the contents of a book. Cross’ first approach was chronological. But transporter development and use was not linear or universal; racers—amateur and pro—used what was available and affordable, from homebuilt open trailer towed by a Mini (if you have to watch your budget) or a Rolls (if you don’t) to the modern Australian 9-axle tandem trailer road trains that carry enough electronic gizmos to orchestrate a moon shot and have greater creature comforts than many living rooms. It’s all in this book—in alphabetical order by maker or team or individual racer or “other.” (The press release cleverly refers to this as “encourag[ing] the reader into a feeling of serendipity, not quite knowing what is coming up next.”) The Table of Contents lists over 150 entries; there will surely be much in there and in the Index you won’t already know about but that’s just what makes this book engaging and surprising.

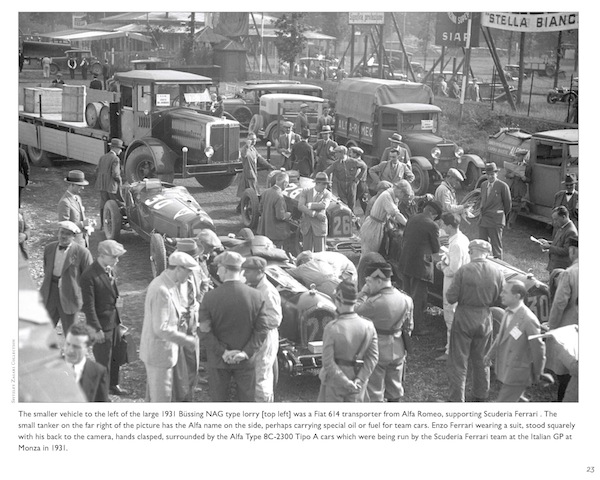

Cross further pared the subject matter down by employing practical and personal criteria. Among the former: only that for which photos and reliable data were available, and only UK and Continental venues are considered. As to the latter: a preference for pre-1960s haulers. A second book that would expand the scope is a possibility. Since not all haulers are trucks the book also shows transport by ship, plane, and rail. He is aided, especially in the writing of the extensive captions, by Danish truck specialist Bjørn Kjer who is a well-respected resource in transporter circles. Extracts from other writers have been quoted to further deepen the reach.

Another matter betraying some arbitrariness is the varying level of detail brought to each entry. For instance, mighty Bentley is given one single page that only talks about the 2001–03 Le Mans effort without even mentioning their glorious early Le Mans history or how people and material got to/from the races then. This entry is immediately followed by nine pages about the White Mouse Stable (the what now? Think Birabongse. Prince. Of Siam.). Authors’ prerogative. . . . To be sure, nothing said above is in any way meant as criticism but merely by way of description. This book should absolutely, unreservedly be shortlisted for your 2012 must-haves!

This is a DaltonWatson book and there is a reason they have the words “Fine Books” in their name. Paper and photo reproduction are as always top-notch, and seemingly small things like embossed cover boards and headbands raise the bar. None of the photos cross the gutter (the book is landscape) so the flat spine works fine although a rounded one would make the book last longer. In a few cases period photos are augmented by modern ones of restored vehicles; there’s also the occasional brochure cover, map, and fine-art piece. A particular tidbit is the first-ever reproduction of pages, along with translation, from the only recently discovered diary of an Auto Union mechanic and transporter driver. Speaking of foreign languages, it is simply remarkable that umlauts, capitalization etc. are done to perfection. Individual Appendixes present proper names, manufacturers, and coachbuilders.

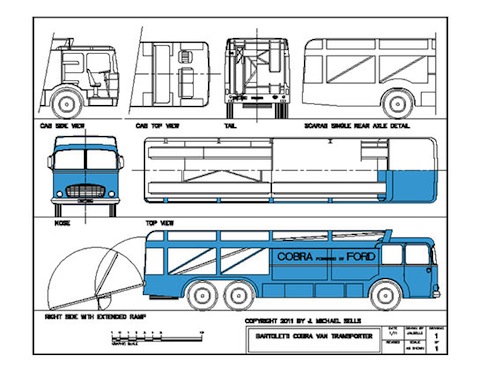

Mention must be made of a really surprising addition, detailed full-color multiple-view technical drawings by CADD operator Mike Sells. Modellers (Sells is one himself) will love this but need to realize that the drawings [a] do not usually show exterior fitments such as sidemarker lights and certainly not detachable bits like roof rails etc. and [b] are based on photos and published dimensions and not blueprints or personal inspection. (He uses these drawings as scalable templates for his own models and you can buy them from him as electronic files; jmsells@sellsbrothers.com.)

Vote for a second volume by opening your wallet for the first one! You will love it.

Copyright 2012, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

Won 2012 Book of the Year award at the International Historic Motoring Awards.