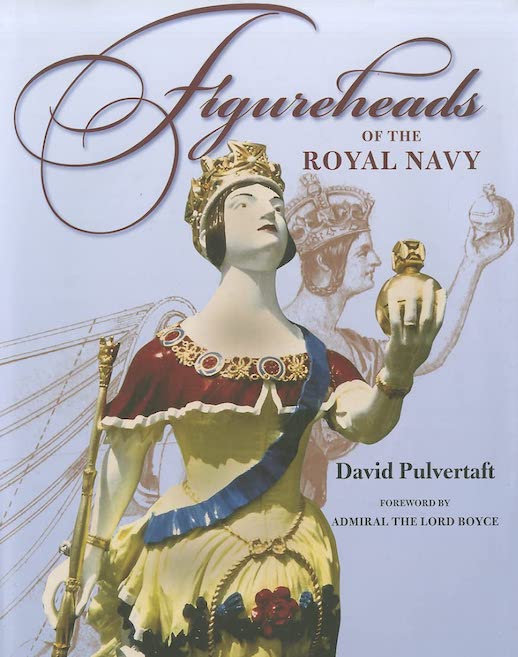

Figureheads of the Royal Navy

by David M. Pulvertaft

by David M. Pulvertaft

From appeasing the fickle gods of the wild and unpredictable seas to scaring the enemy to reassuring the crew, nautical figureheads have a long and colorful history rife with symbolism. Be it the tribesman’s canoe or the ancient Egyptian, Roman or Phoenician ships, most cultures decorated the stems of their boats in some way or other.

As one of the great sea-faring nations, Great Britain took particular care to name its merchant and navy vessels in a manner befitting their status and missions and to adorn them with figureheads that gave unique and appropriate expression to that name. The connection between name and figurative representation is especially relevant in the case of military vessels and that is the angle this book examines.

In a typical case of “better late than never,” then Rear Admiral Pulver only considered in his last year of active duty (1992) that soon he would no longer have unfettered access to naval establishments and thus decided to take “an active interest” in Royal Navy figureheads then and there. Many years of research later he wrote the 2010 book The Warship Figureheads of Portsmouth (ISBN 978-0752450766, The History Press) that took a different tack from this new one. It considered a much smaller selection, both of ships and carvers, but gave the ships’ operational history and featured Kevin Dean’s excellent figurehead illustrations.

This book casts a wider net in terms of artifacts covered and is much more focused on the carvers and the carvings, the process of commissioning such work, and the need to preserve what still exists. It is disheartening to realize that of the 5000 warship figureheads created during the 350 years discussed here, only ca. 4 percent—about 200 items!—survived and details are known of only 20%. Already in 1913/14 when Douglas Owen, then secretary to the Society of Nautical Research, toured the royal dockyards to take stock of the figureheads he lamented that too much had already been lost—and that was long before the founding of the National Maritime and the Royal Naval Museum. More have been lost since and that is why Pulver’s book aims to describe for the record the lost, not the surviving work. The latter, though, is included in a 31-page list by ship name/date/type, figurehead origin/date/cost, and current location or archival reference number. This list may well be the most comprehensive account in one place and will be of inestimable value to the historian and collector who really haven’t had anything of reference-level status since L.G. Carr Laughton’s 1925 Old Ship Figure-Heads & Sterns (reprinted 1991 by Conway). Sterns and quarter galleries, although usually done by the same carvers, are expressly not part of Pulver’s book because they are a less specific expression of the attributes embodied in the ships’ names which is Pulver’s primary interest here.

The Foreword by Admiral the Lord Boyce closes with praising the book as “a work of real scholarship that throws much new light on this poorly understood aspect of naval history.” And right he is; while there are all sorts of pictorials and collector guides about figureheads, scant indeed are descriptions of the actual process of how the carver was selected, instructed and supervised, or how the Surveyor of the Navy approved or amended the design, or even the layers of bureaucracy between submitting the original sketch to it becoming part of the national Archives.

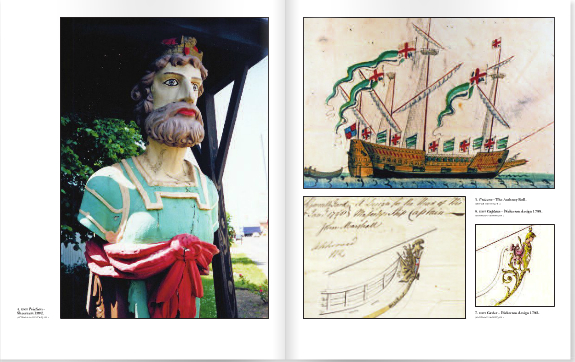

Pulver begins with the criteria for selecting names for fighting ships since around the mid-1500s and focuses on those that offer a “suitable cross-section of subjects and images.” Throughout, the text has notes (incl. archival reference numbers) in the margins. The line art is in many cases the carver’s own proposal or, in lieu of that, a ship’s plan and even the two sets of John Player cigarette cards from 1912 and 1931. Photos of pieces that are lost are obviously hard to come by so period ship models (routinely created on approval of design by the RN or as presentation pieces) serve as stand-ins.

Different kinds of figureheads are covered (demi-heads vs. busts), as are the relationship between the ship’s name or role and the budget for carving and additional decoration such as on the trailboards that connect the figurehead with the hull of a ship. A survey of prominent carvers and figurehead collections then leads to in in-depth treatment by century, beginning with the 16th. The 19th century makes up the bulk of the book and is further divided by subject matter: beasts, birds, famous people, geographic, miscellaneous, mythology, occupations, prize and commemorative names, and royalty. When sail gave way to steam and ship construction made figureheads superfluous, ships had bow decorations for a while and these are presented in a brief closing chapter.

Especially for the new reader it would have been useful to explain how the figureheads—often of enormous size and weight—were transported and attached to their ships, or how their exposed location at the front of the ship influenced their design in regards to protruding elements such as arms, shields, etc. and how the inevitable repairs were effected.

Color photos are bundled into a separate section. Bibliography/Sources. Index contains ship names only.

If you have a carver in the family, don’t be surprised if no banister in the house is safe any longer!

Copyright 2012, Charly Baumann (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter