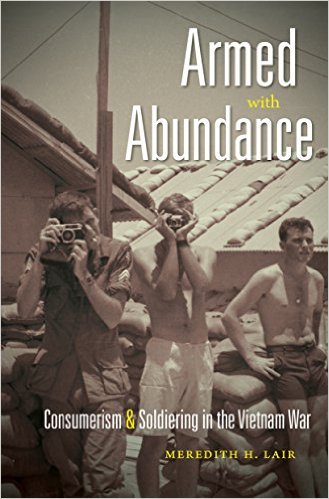

Armed with Abundance

Consumerism and Soldiering in the Vietnam War

The usual perception of what American servicemen typically experienced during their tour in Viet-Nam during the war tends to be centered around that of the infantry grunt, hacking his way through the jungle or slogging across rice paddies, every moment just seconds away from a firefight against the Viet Cong or North Vietnamese. Living in primitive conditions on fire support bases between patrols, with the threat of being overrun with nightly rocket or mortar attacks was a constant danger that had to be endured. Films, television, books, and the stories of Viet-Nam veterans tend to reinforce this perception.

However, given that perhaps only about 10% of the American servicemen who served in Viet-Nam actually experienced or were in direct support of close, physical combat on a recurring basis, this perception certainly seems to be odds with the reality of a typical tour during the Viet-Nam war. It would seem that most of the American military personnel sent to Viet-Nam served in support roles as part of a vast administrative and logistical network established to support combat operations. In other words, the vast majority of American servicemen spent their time in the rear echelons, rarely experiencing the hardships and dangers of those actually in combat.

Armed with Abundance, written by Dr. Meredith H. Lair, an associate professor at George Mason University, is among the few works of originality and creativity regarding the Viet-Nam War and the American experience there to appear in many, many years. Rather than continue to devote attention to the experiences (real or imagined) of the very few, Lair focuses her attention on the experiences of the many, those more often than not referred to as the REMFs—the Rear Echelon Motherfuckers, or more politely as Those in the Rear with the Beer.

If soldiering in combat was fraught with its obvious dangers, the lot of the REMF was not always necessarily one of comfort and ease. Tedium, ennui, boredom, and the monotony of the routine of the office, motor pool, ammo dump or flight line while thousands of mile from home often had its effect. Just as the frequency and likelihood of combat varied due to time and place, so did the challenges of those in the read echelons. In the early years, while the American logistical infrastructure was being developed and put into place, support troops often had to deal with both the many difficulties of establishing the support bases and the primitive living conditions endured while doing so.

Once the support networks were established, however, life in the large support bases was not necessarily all that much different than being stationed in Europe or even back in the United States. The large, sprawling base camp just northeast of Saigon, Long Binh, the headquarters of the American command in Viet-Nam, had a shuttle bus service for soldiers to transport them around the vast camp. There was a large post exchange (PX) on base along with several smaller PXs scattered about the post, along with several snack bars in addition to the many mess halls. In addition, there was a skeet range (!), a go-kart track, miniature golf courses (2), basketball courts (81), volleyball courts (64), football fields (3), a number of other basic athletic facilities, Red Cross clubs, libraries, along with other recreational facilities such as the many unit day rooms, and the enlisted, noncommissioned officer (NCO), and officer clubs for those stationed on Long Binh.

This sort of recreational and morale support, albeit at a lesser level, could be found at the base camp for the headquarters of the 9th Infantry Division in the Mekong Delta, Dong Tam. There was a swimming pool, library, Red Cross club, and the usual basketball and volleyball courts, along with a good-sized PX, and numerous clubs for the enlisted soldiers, NCOs, and officers. Even down at the smaller brigade base camps, such as that for the 9th’s 3rd Brigade at Tan An, there was a relatively well-stocked PX along with the usual clubs for those stationed there.

Professor Lair’s book is one I would highly recommend as being an essential guide to gaining a more rounded understanding to the experience of the American serviceman during the Viet-Nam War. It is a much-needed balance to the usual material produced regarding how American soldiers served in Viet-Nam. It is social history of the highest order, which should open new avenues of interpretation of that war and the Americans who served there and the perceptions of their experiences. It is not only well-researched with excellent analysis leading to fresh interpretations, but it is also well-written, meaning that the general reader as well as one from the academic community will find much to consider and contemplate.

Copyright 2016, Don Capps (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter