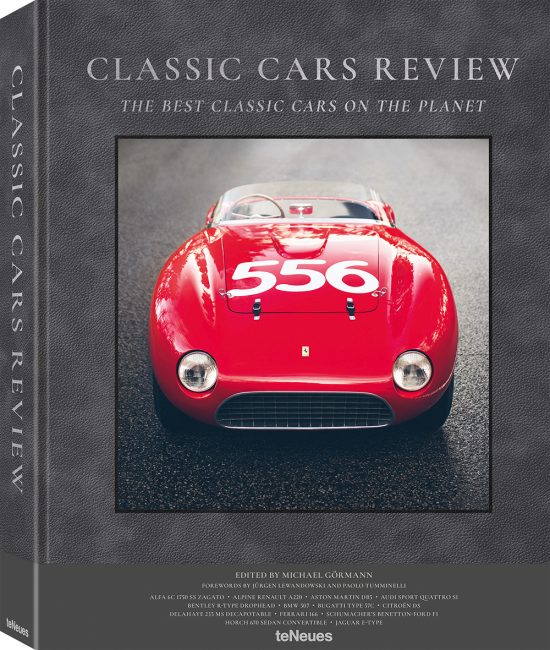

Classic Cars Review: The Best Classic Cars on the Planet

by Michael Görmann, editor

“Only those who have felt, heard, smelled, and experienced a classic car at close quarters can have an inkling of how a piece of historic engineering can give a person such pure thrill. It is the enjoyment of ingenuity, vintage craftsmanship, and all the brilliant designs from engineers who passed away long ago. In short: It is the experience of cultural history on wheels.”

(English, German) This book has been called, more than once, a “concours d’elégance in book form,” by probably well-intended reviewers—who totally did not get what the book is really about. Sure there are a good number of concours-worthy and otherwise important / rare / expensive cars in the line-up here, but their preservation and the lifestyle that has grown up around them is merely the byproduct of something else: connoisseurship—as opposed to an investor or flipper mentality. Right from the outset the book’s editor—who quite fittingly describes his role as that of a curator—and his cohorts make it a point to establish that an appreciation of the classic car, or by extension any “special” car regardless of vintage, begins with an affinity for craft and creativity, and consequently an ability to discriminate. A quote in the Foreword, attributed to car designer Walter de Silva, points the right direction: “It is easier to draw a supercar than a new VW Golf.”

A book merely has to look like this one to be—indiscriminately—dismissed by many as a cream puff, a coffee table book—the horror. Yes, it is a 14.5″ tall 10-pounder bristling with splashy photos and high design and a textured suede-like cover, and it literally can only fit on a coffee table or sideways on a bookshelf, but it is not a vainglorious exaltation of superficiality. Consider, for instance, that one of the Forewords is by Paolo Tumminelli, someone who wears many hats in the design world and wouldn’t seriously want to dilute his reputation. The same applies to automotive journalist and amateur racer Jürgen Lewandowski who wrote the other one.

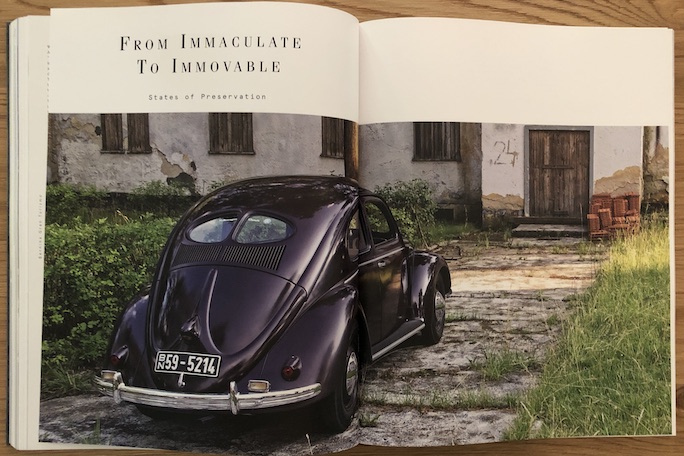

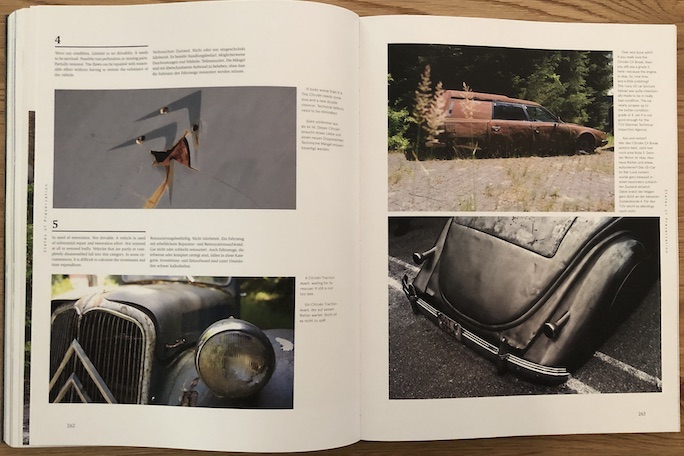

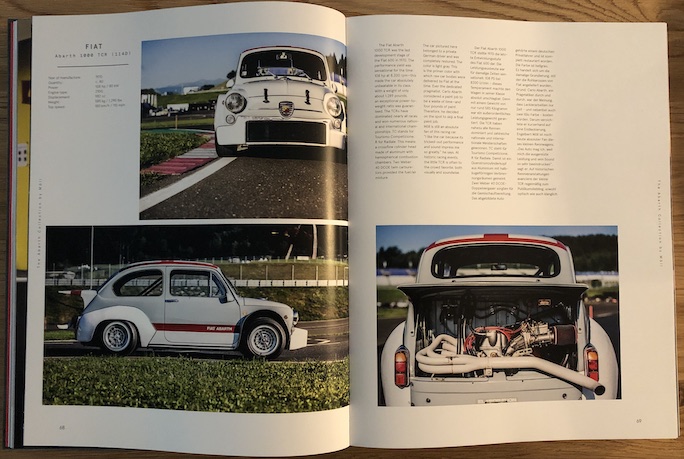

You only have to look at the Table of Contents to realize how wide a net the book casts. From multi-car collections (themed or subjectively random) on the one end to single cars on the other and the reasons for their desirability to the specific owner/custodian the pendulum swings all the way to such practical matters as how to rank car condition to stated value-insurance or full-service management firms that handle everything from buying to servicing. The firms and services described are by no means the only ones in their fields but discussing any at all may open the eyes of especially the person who is only just beginning their journey.

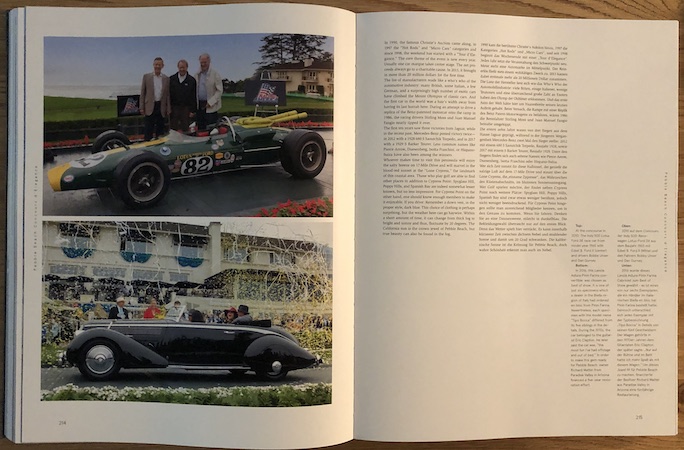

At some level, and for people of means usually intentionally so, ownership of a special car becomes almost inevitably an admission ticket to a very specific world, from being invited to show at Pebble Beach to letting it all hang out on the Gumball. All this is covered too. As to car info, know that this book is not meant for “looking stuff up”—of course there are specs and history both generically in terms of the model and often also specific to the car shown. Whether it’s a Mini Cooper or the Opel Raketenwagen—what the wide variety of cars in this book have in common is that, for reasons large and small, subjective or objective, they mean something to someone.

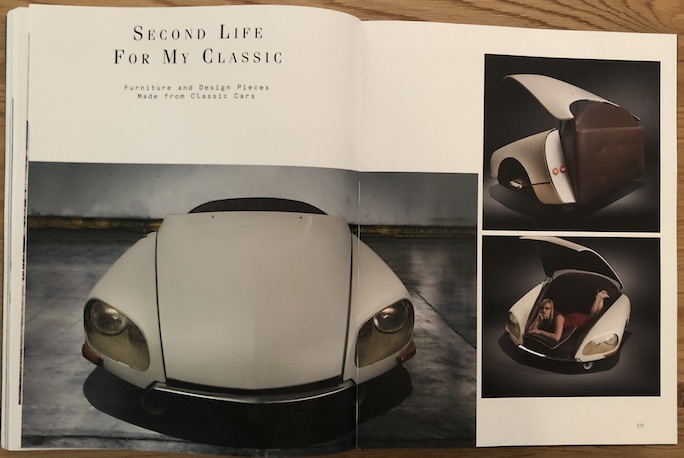

There is even a section on repurposing car parts as art furniture, which brings us to the aforementioned editor/curator. Even though the text does not say so (it coyly talks about “a collector in Munich” which happens to be where Görmann lives), this furniture is almost certainly by him because it is one of his “hobbies.” A journalist by trade he likes to say he doesn’t have a “job” which, in the sense of a linear career trajectory, is true enough.

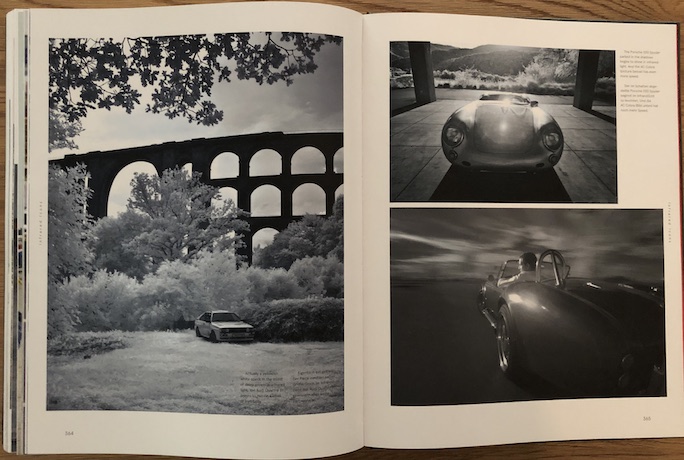

He does like things mechanical, and writes about and photographs them. This latter aspect will interest photographers because among the photographers this book showcases (Sayn-Wittgenstein, René Staud and others) there are also Görmann photos, specifically examples of his [near] infrared light photography (below) which even though it has been commercially viable since the 1930s really does not have much of a mainstream presence (not to be confused with thermal imaging which is “far infrared”). He is also into mechanical watches and makes cufflinks out of old movements—another hobby with a commercial dimension. The reason to mention this is to bring home the point made earlier: connoisseurship is what the book singles out.

Copyright 2019, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter