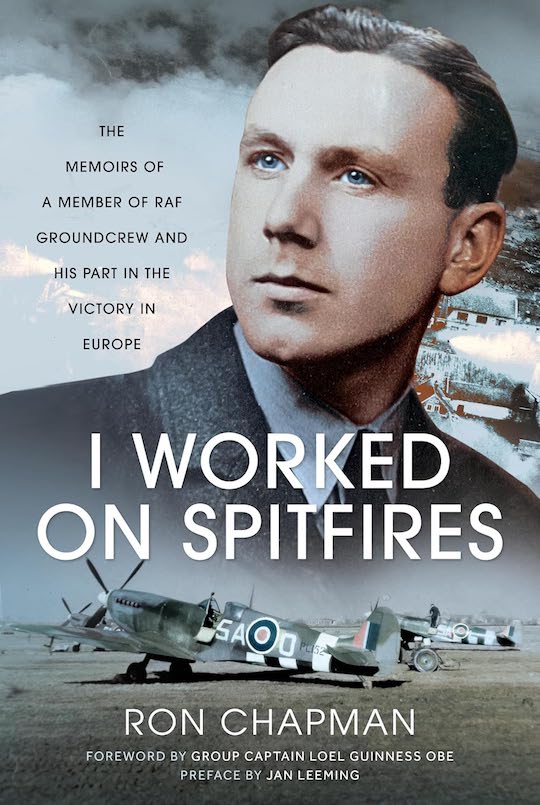

I Worked on Spitfires

The Memoirs of a Member of RAF Groundcrew and his Part in the Victory in Europe

by Ronald L. Chapman

by Ronald L. Chapman

“This then was the dilemma in which I found myself; after searching libraries throughout the country for any reference to the men of France who escaped in large numbers from all parts of their country, including those Frenchmen who succeeded in reaching Great Britain from as far away as French Canada and the French Colonies.”

If you fail to see what that excerpt has to do with the title of the book, well, you’ll not want to know that the promo material says these “memoirs provide a unique insight into the functioning of a fighter unit from the perspective of fitters, riggers, and armourers.” Well intended but rather a stretch.

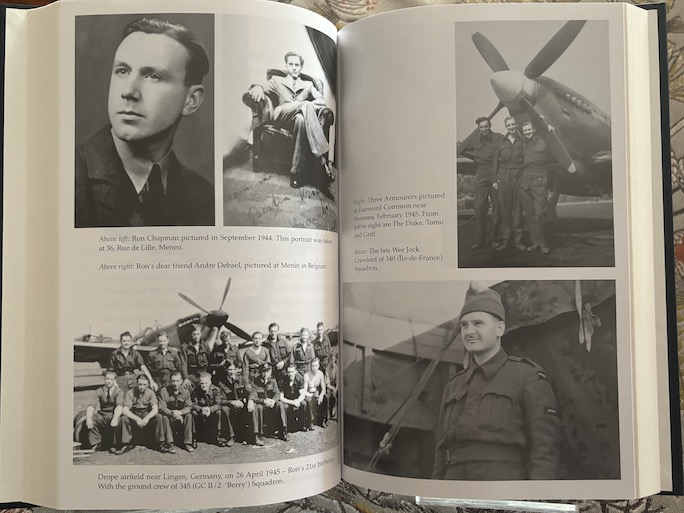

The author really did work on Spitfires, in WWII, but his work experience—the technical or logistical aspects of maintaining aircraft during wartime—are not at all what this book is about. Rather, it is about the lived experience of a soldier in the field—food, sleep, toilets. One of the two Forewords is much closer to reality: “The story tells us much about the people, the places, the work, the plays, the joys, the sorrows, the fear, the gallantry, the misery, the comradeship and all those other things that go to make up what happens in war.” These words are by the CO of the RAF station where the Free French Squadron was formed, and it is this FFS dimension that sets this memoir apart from others, and it is one particular French aviator’s place in history that finally sparked interest in the publication of Chapman’s memoir four decades after it had been written—which was already four decades after these events had transpired.

In other words, it’s a story long overdue and worth knowing. Contemporaries to whom the author had shown the manuscript in the 1980s deemed it important and saw its value as a testament “for the generations to come.” The author didn’t live to see the book published, which is sad, but it did finally happen, which is good. The first dozen pages explain all those circumstances.

At the time Chapman turned his diaries and notes into a manuscript in the 1980s, awareness of the role of the foreign aviators serving in the RAF—French, Poles, Czechs—was already waning so he devotes the first few chapters to summarizing the origins of the FAFL, the Forces Aériennes Françaises Libres, created by Charles de Gaulle in 1940, in opposition to that part of the French government that had chosen to collaborate with the Germans after the French had capitulated. What is surely not widely realized is that those FAFL pilots who wanted to throw in their lot with the British, which meant breaking away from their squadrons, sometimes having to steal aircraft to facilitate their escape, were in many cases actively sabotaged by their “countrymen” who now treated them as traitors. All this is relevant to the book because Chapman’s outfits were seconded to those RAF stations that took in FAFL pilots, and also New Zealanders, first on Hurricanes, then Typhoons, and then Spitfires. That these wings or squadrons operated on an itinerant, nomadic basis and thus were billeted in tents and encountering often “appalling” living conditions adds another dimension.

Today’s reader will be in dire need of having this all sorted (also the historic ties between France and Scotland), and will appreciate why it takes about half the book before Chapman ever gets around to introducing himself to the story, covering birth (1924), parents, growing up in London’s East End, schooling, and various work experiences before the outbreak of war upends everything, prompting him to enlist in the RAF at the tender age of 17, to his parents’ dismay.

Little is said about the training syllabus, any vocational choices or preexisting skills, and certainly not about aircraft, so, to beat that dead horse once more, the whole aircraft maintainer/armorer bit is peripheral to this otherwise thoughtful and necessary memoir.

Copyright 2024, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter