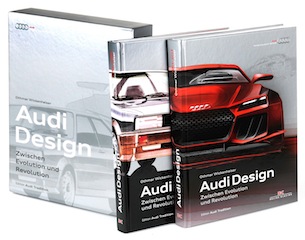

Audi Design, Zwischen Entwicklung und Revolution

(German—but before you skip this review, know that an English edition is due out towards the end of 2015, ISBN 978-3-7688-3782-8.)

This is an exhaustive insider’s look at the process of automotive styling, using Audi as a case study. Anyone curious about car design will find this book enlightening and anyone who has the four rings tattooed on a body part simply must have it. The latter group will probably already have the author’s 2005 Audi Design – Automobilgestaltung von 1965 bis zur Gegenwart (ISBN 978-3894791605), by now a standard work on the subject. Wickenheiser considers the new book a “continuation” of the old one.

And while the new book does pick up where the other left off—Audi having put out more designs in the eight years since the first book came out than it had in the entire forty years prior—it also deals with the pre-1965 history. Specifically, it begins in the mid-1940s with a discussion of industry-wide and in fact global design trends such as pontoon-style (first shown by Kaiser-Frazer in the US) and tail fins. There is plenty of reference to other marques here so, again, even the non-Audi reader will find much of universal usefulness. Also, throughout, the book often crossreferences highly styled consumer goods from household appliances to art furniture, even fashion.

This book has Audi AG’s fingerprints all over it—in a good way! Audi is the publisher of record, Wickenheiser (b. 1962) was an Audi designer in the 1990s (under design chiefs Hartmut Warkuß, J Mays, and Peter Schreyer, and the firm’s design department had a hand in the layout. Wickenheiser is first and foremost an academic, a scholar beholden to the rigorous pursuit of facts—which means he is not averse to following an objective analysis to a critical conclusion, even one critical of Audi. To emphasize the latter it would be good to know something the book doesn’t spell out, what with not blowing one’s own horn and all that. He was Germany’s youngest design professor when he switched to academia in 1996, is a founding member of the German Design Council, a subject matter expert on the International Council of Industrial Designers, has implemented industry-changing practices in regards to exposing his students to real-world experiences, and is a widely published and consulted theorist who still considers his practical experience as a car designer a dream job. (There’s only one job he’d like better: being a jazz pianist.) And while he does consider Audi’s Multi Media Interface the most beautiful car detail of all time, the Porsche 911 tops his list of most beautiful cars ever.

This book has Audi AG’s fingerprints all over it—in a good way! Audi is the publisher of record, Wickenheiser (b. 1962) was an Audi designer in the 1990s (under design chiefs Hartmut Warkuß, J Mays, and Peter Schreyer, and the firm’s design department had a hand in the layout. Wickenheiser is first and foremost an academic, a scholar beholden to the rigorous pursuit of facts—which means he is not averse to following an objective analysis to a critical conclusion, even one critical of Audi. To emphasize the latter it would be good to know something the book doesn’t spell out, what with not blowing one’s own horn and all that. He was Germany’s youngest design professor when he switched to academia in 1996, is a founding member of the German Design Council, a subject matter expert on the International Council of Industrial Designers, has implemented industry-changing practices in regards to exposing his students to real-world experiences, and is a widely published and consulted theorist who still considers his practical experience as a car designer a dream job. (There’s only one job he’d like better: being a jazz pianist.) And while he does consider Audi’s Multi Media Interface the most beautiful car detail of all time, the Porsche 911 tops his list of most beautiful cars ever.

You could stop reading here and just get the book based on the above, trusting that Wickenheiser won’t lead you astray. But if Audi hadn’t been on your radar yet, here is some more background to establish why this brand’s journey from blah to design-forward is noteworthy. Until Auto Union was taken over by VW in 1964 the marque did not have a signature styling cue or articulated a design philosophy. Today, an Audi is recognizable at a glance. People may have been slow to appreciate what was coming when the fifth generation of Audis came out with the A6 of 1997 but the TT a year later put the world on notice that he days of boring Audis were over. Which is why Ulrich Hackenberg, nowadays member of the Board of Management of AUDI AG with responsibility for Audi’s Technical Development, can say in his Foreword to vol. 1 that “design is our customers’ top reason to buy Audi.” He should know because after four years at Audi he was put in charge of Concept Definition in 1989 and later took over the technical project management of the entire product range, i.e. Audi 80, A3, A4, A6, A8, TT and A2, as well as numerous concept studies and show cars. (VW Group design chief Walter de Silva and Audi design chief Marc Lichte wrote Forewords to vol. 2.)

People may have been slow to appreciate what was coming when the fifth generation of Audis came out with the A6 of 1997 but the TT a year later put the world on notice that he days of boring Audis were over. Which is why Ulrich Hackenberg, nowadays member of the Board of Management of AUDI AG with responsibility for Audi’s Technical Development, can say in his Foreword to vol. 1 that “design is our customers’ top reason to buy Audi.” He should know because after four years at Audi he was put in charge of Concept Definition in 1989 and later took over the technical project management of the entire product range, i.e. Audi 80, A3, A4, A6, A8, TT and A2, as well as numerous concept studies and show cars. (VW Group design chief Walter de Silva and Audi design chief Marc Lichte wrote Forewords to vol. 2.)

Wickenheiser is keen to set a higher bar than other design writers and lays out the formal criteria for his discipline, encourages the reader to go the extra mile and become familiar with the jargon (a Glossary is part of the book), and casts a wide net to school the reader’s eye to apprehend that which every product designer worth his salt wants to covey to the people they design for: “styling” is not just about making things subjectively pretty.

So, following the aforementioned 1945–65 preamble the book offers, by era and model, a detailed discussion of all aspects of the design process from initial brief to execution on a car, including concept cars. Every character line on the exterior and every switch on the dashboard is there for a reason—not necessarily one every customer can relate to. If you don’t foresee an Audi in your garage, how about their sports gear (bikes, skis) or at least a foosball table or a wristwatch, luggage, or the ($140,000!) Bösendorfer Grand or Leica camera?

So, following the aforementioned 1945–65 preamble the book offers, by era and model, a detailed discussion of all aspects of the design process from initial brief to execution on a car, including concept cars. Every character line on the exterior and every switch on the dashboard is there for a reason—not necessarily one every customer can relate to. If you don’t foresee an Audi in your garage, how about their sports gear (bikes, skis) or at least a foosball table or a wristwatch, luggage, or the ($140,000!) Bösendorfer Grand or Leica camera?

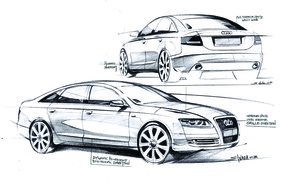

There are about as many drawings as there are photos, around 450 each, and your eyeballs will be darting back and forth as if you’re watching tennis. The captions are very precise and you’re sure to become aware of things you never consciously processed before. Wickenheiser being the meticulous thinker he is writes in a way that, in German, makes for long, nested, complicated sentences but it’s nevertheless engaging and rich in context. (The English version will surely read easier simply because there are so many fewer words, unless it’ll be translated by someone who can’t free himself of the syntax, an all too common handicap!)

There are about as many drawings as there are photos, around 450 each, and your eyeballs will be darting back and forth as if you’re watching tennis. The captions are very precise and you’re sure to become aware of things you never consciously processed before. Wickenheiser being the meticulous thinker he is writes in a way that, in German, makes for long, nested, complicated sentences but it’s nevertheless engaging and rich in context. (The English version will surely read easier simply because there are so many fewer words, unless it’ll be translated by someone who can’t free himself of the syntax, an all too common handicap!)

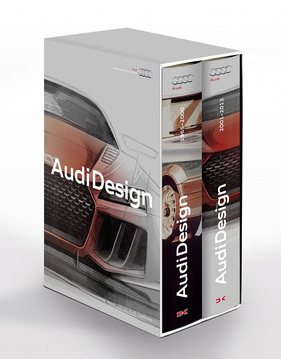

Obviously the book doesn’t just look backward but forward too. Appended (to vol. 2 are mini bios of Audi design chiefs, a list of design awards, Glossary, Chapter Notes, and Sources / Bibliography; no Index.

The carmaker’s role in this book surely accounts for one other thing: the affordable price. A 640-page, 10-pound book with all the bells and whistles doesn’t happen for €98 unless someone swallows some of the cost.

Won the German Design Council’s 2015 award for design at the Automotive Brand Contest.

Copyright 2015, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter