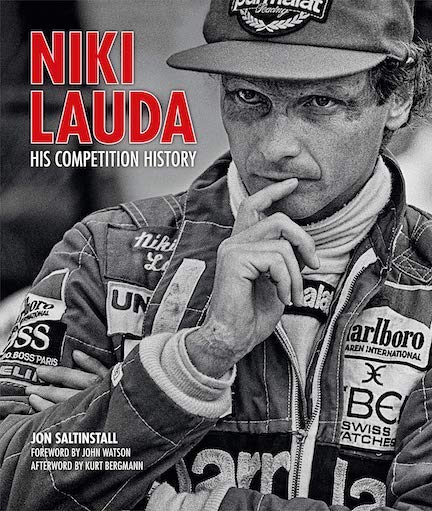

Niki Lauda: His Competition History

“A lot of people criticise Formula 1 as an unnecessary risk. But what would life be like if we only did what was necessary?”

–Niki Lauda

I need to declare an interest. The last time I shed a tear at the death of a racing driver was when Andreas Nikolaus Lauda (b. 1949) died on May 20, 2019. But, lest you think I incline to lachrymosity, the previous occasion was 44 years earlier, when Graham Hill died as his Piper Aztec crashed at Arkley Golf Course. The sport being what it is, too many names had punctuated the intervening years.

However, until last May, while always saddened by a driver’s passing I had maintained a Brit’s trademark stiff upper lip. Jon Saltinstall quotes the racing journalist Nigel Roebuck as saying about Niki Lauda that “I have never met anyone who reminded me of him” and those words resonated deeply with me. Because Lauda was not only a sublimely gifted racing driver but also searingly smart, almost painfully frank and, beyond question, he was the most courageous racing driver I have ever seen. Lauda’s work ethic and commercial savvy built upon Jackie Stewart’s approach, becoming the template for the generations of Formula 1 driver that succeeded him.

But my bias does the author no favors as, in the case of Lauda, I set the bar just about as high as it will go, and any book about him needs to do him full justice. I am delighted to say that this book, nine years in the making and published mere weeks before Lauda’s death, is a worthy addition to the canon of Lauda literature (talking of which, may I especially recommend Formula 1, The Art and Technicalities of Grand Prix Driving, the 1975 book Lauda wrote with Herbert Volker and Dr. Fritz Indra in 1975?).

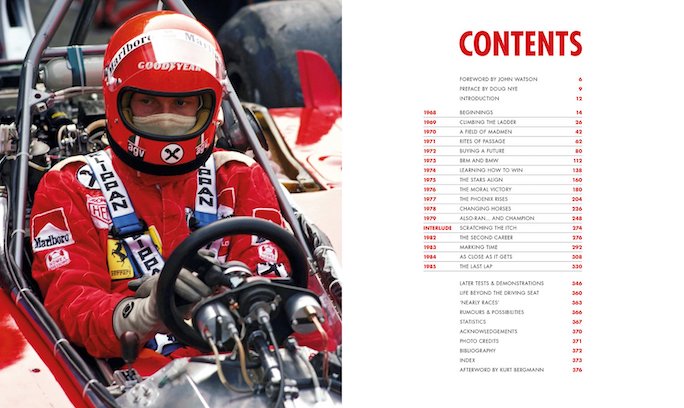

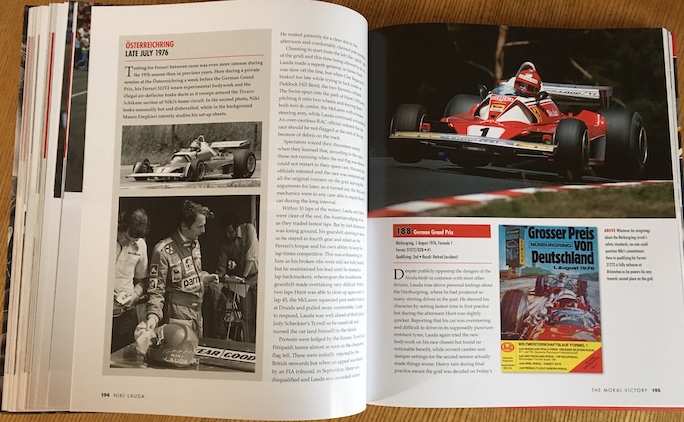

Jon Saltinstall’s book is not intended to be Niki Lauda’s biography per se, as its essence is simply to list every single event in which Lauda competed, from his debut in an Austin Mini Cooper S in April 1968 at the Bad Mühllacken hillclimb to his final Grand Prix, 315 events and nearly eighteen years later, at Adelaide in the McLaren MP4/28-1. The author devotes the final part of the book to Lauda’s appearances post retirement, also including statistical tables of his race career. The book has reader-friendly dimensions of approximately 10 x 12 x 1 inches and runs to 376 pages with myriad illustrations, mainly in color but also including b/w shots of the driver’s early career. The foreword is written by Lauda’s Brabham and McLaren team mate John Watson, and there is also a preface by the highly respected motorsport historian Doug Nye.

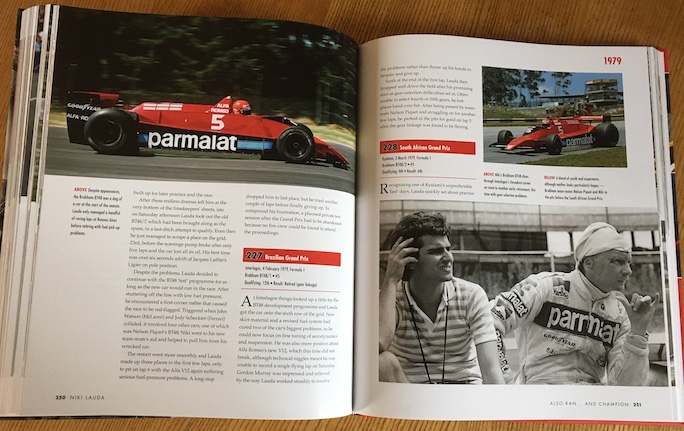

I think that Saltinstall took exactly the right approach to writing this book by reflecting his subject’s pragmatism, and sticking almost entirely to the facts. Each chapter contains a brief account of Lauda’s performance in every event, is largely free of opinion, and concludes with a short passage summarizing his racing year. Almost every event is illustrated, often (but not exclusively) with a picture of Lauda at the wheel. The period detail entranced me—I loved the reproductions of race programs (‘Int Hansa Pokal-Rennen Nürburgring 28/29 Jun 1969’) and seeing photos of the youthful Lauda with friends and rivals such as Red Bull hard man and former BRM driver Helmut Marko. As Lauda’s career progressed to the upper echelons of the sport, the diversity of the machinery did diminish, resulting in there being many pictures of the same type of car. However, when the car in question is, for example, a BMW 2800CS/CSL or (especially) the divine Ferrari 312T you will hear no complaints from me. It was also good to be reminded of just what a dog’s dinner the unloved and uncompetitive March 721 looked, and it was even better to see a grainy (and I suspect previously unpublished) b/w picture of a Fiorano test of the unraced Ferrari 312PB-74.

It is inevitable that the book will bear testimony to the very different life young racing drivers led in the late 1960s compared to the one led by their modern counterparts. There was no career kick-start in karting, no simulator work back at the team base, and no data logging or debriefs. Instead, there was resourcefulness and self-sufficiency allied to a camaraderie amongst the racing gypsies who trailered their Formula Vees around a world very different to today’s almost border-free European Union.

John Saltinstall painstakingly details the trips to forgotten race circuits behind the Iron Curtain—Sapron and Budapest in Hungary, Belgrade in what was then Yugoslavia—and the long road trips to Sweden and Finland, Monza and Nogaro. It was useful to be reminded that Niki Lauda belongs to that group of drivers who enjoyed reasonable, but unremarkable success in the lower formulae, those whose light never shone with the intensity of a Moss, a Rindt, or a Senna until they became Grand Prix drivers. I first saw Lauda at my own very first Formula 2 meeting, held on March 14, 1971 at Mallory Park in England’s East Midlands. It was Lauda’s 66th event, which he contested in a March 712M, but I hardly remember him at all, and I needed the book to remind me that he qualified tenth and didn’t feature in either heat. My little coterie of friends dismissed him as just another journeyman chancer with more budget than talent, not on the same planet as Ronnie Peterson whose speed had so entranced us—or at least it had before he crashed… But we had to change our tune two years later, as we watched Lauda’s BRM P160E rocket into second place from seventh on the grid—headed only by Ronnie Peterson’s Lotus 72—on the restart of the 1973 British Grand Prix at Silverstone.

The rest is history, perhaps even legend, from the glory and tragedy of the Ferrari years, to the curate’s egg of Bernie Ecclestone’s Brabham redux, the sudden retirement in ’79 and the triumphant return with McLaren. Thanks to my advancing years, some of the story feels almost like recent history and it was only when reading Saltinstall’s meticulous reportage that I was reminded of how much I have forgotten! Such as how unreliable Lauda’s McLaren MP4/2B was in his final season in 1985, only three finishes, including his last victory at the Dutch Grand Prix which I had watched, entranced, from the sand dunes of Zandvoort. Such as the fact (if I ever even knew about it at all) that in 1977 he’d helped out Ligier by testing the JS7 before trying out the Fittipaldi F5 for size. But one thing I had never forgotten was that, regardless of where he had qualified, Lauda could never be discounted, and there was often a feeling of inevitability at his ascent through the field. The Portuguese Grand Prix in 1984 epitomized this, with Lauda starting 11th but rising to second to win his third championship, by half a point from team mate Alain Prost. It is fitting that the author quotes Prost’s words on that season: “I didn’t know Niki when I came to McLaren, but I believed him to be completely honest; by the end of 1984 I was certain of it.”

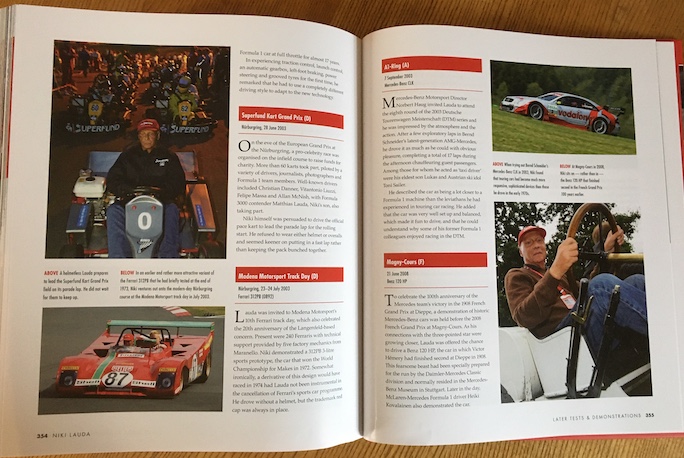

Saltinstall also describes the many different personae Niki Lauda had after his retirement from race driving—the airline boss who stood up to Boeing after the Lauda Air crash in 1991, the TV pundit, the BMW and Mercedes brand ambassador, the head of Ford’s Premier Performance Division (which included the ailing Jaguar F1 team that evolved into today’s Red Bull), and the Mercedes F1chairman and Lewis Hamilton mentor and confidant. His was an exceptionally full life, well lived despite the legacy of ill health from his 1976 Nürburgring crash, and it was the right decision to include brief details of these roles in the book. And how I loved the anecdote about Lauda’s race trophies; notoriously, Lauda had given the cups and shields to the local gas station, in return for free car washes. But what the author also reveals is that, after the station’s owner died, Lauda recovered the now tarnished and uncared-for silverware and had it restored before, again entirely true to character, selling it on eBay!

Saltinstall deserves much credit for this book, and the huge amount of research that must have gone into its creation. Publisher Evro is also to be congratulated for producing a high quality book that feels worth its considerable price. The book is a recommended read for everyone who followed Grand Prix racing in the 1970s and ‘80s. But it is an essential read for those who already respect and admire Lauda. And if you belong to generation Y or Z, for whom even Michael Schumacher might seem to be a figure from prehistory, reading this book might remind you of the famous LP Hartley quotation: “the past is a foreign country, they do things differently there.”

I haven’t tried to hide my admiration of Lauda the man in this review, as to do so would have been dishonest, if not impossible. I don’t doubt that Jon Saltinstall admires him as much as I do, if not more (it is, after all, the very reason he embarked on this, his first writing effort) and I wonder if he was as moved as I was to learn that Lauda, the most unsentimental of men, “was buried…wearing the red racing overalls from his later years as a Ferrari driver.”

I said at the beginning of this review that I had been reduced to tears only twice by a racing driver’s death but, after reading those words, I have a confession to make. Now it is thrice.

Copyright 2019, John Aston (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter