How Did I Get Here?

Memories of Six Decades in Motorsport, and Musings on the Future of Formula 1 and the Planet

by Peter Wright

by Peter Wright

“What occupies me, to the detriment of almost everything else, is how to overcome a problem. . . . Taking a concept, proving it, sorting out the essential details . . . is what lights my fire”

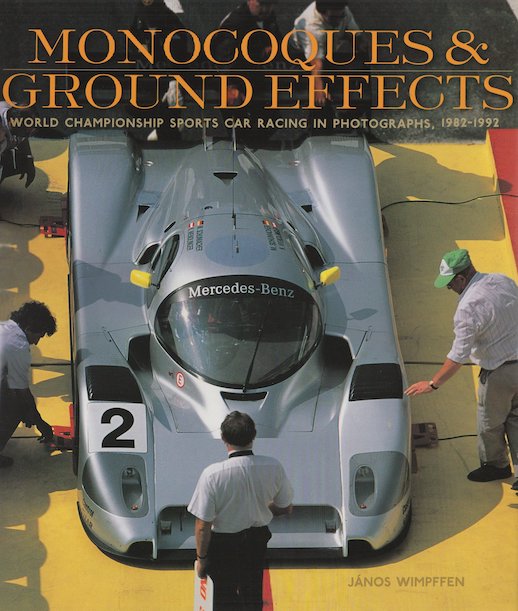

To say that Peter Wright is the guru of ground effect is like saying that Sir Ian McKellen is just the Gandalf guy. To characterize a career spanning more than half a century to just one role is both glib and reductionist, and both deserve better.

In this fascinating autobiography, Peter Wright takes us through a long career, studded with so many highlights that he’s a shoo-in for Renaissance Man status. Of course, the Lotus ground effect saga is recounted, with insights only a key player at the court of Colin Chapman could offer, but it is testament to Wright’s remarkable career that the Lotus 78/79 story is completed with over fifty chapters of the book still remaining.

Pre-2000, only the more knowledgeable followers of motorsport showed interest in the designers who created the cars raced by champions from Surtees to Schumacher. But now that Formula One has a global TV audience in the hundreds of millions, and a social media profile beyond Bernie Ecclestone’s imagination, even the casual fan knows about Adrian Newey’s lucrative move from Red Bull to Aston Martin. Books like Newey’s How to Build a Car (2017) or The Perfect Car (2018), about John Barnard, sold in their thousands and race car design, once the province of behind-the-scenes boffins, has become the new rock ‘n roll of motorsport. Peter Wright, like his peers Tony Southgate, Derek Gardner, and Gordon Coppuck was a name known only to the cognoscenti but this book will ensure that nobody will ever characterize Peter Wright as a one trick pony.

The book is self-published but that should carry no stigma. How Did I Get Here? is a pleasingly designed, 360-page book with the solid look and feel of a “name” publisher’s product. It is well written, with only the occasional typo (curiously, only on surnames) hinting that this book didn’t come from Simon and Schuster but from an off-grid barn conversion in the Welsh Borders. The author tells his story in a broadly linear way, but when a life has been as rich as Wright’s, the conventional approach is the right one. Believe me, it’s hard to keep up with just how busy this man’s life has been!

Wright was what used to be termed a child of the British Empire, the son of academically gifted parents who’d met at the Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge. Childhood was divided between Sudan, where Wright senior was head of Northern Province Surveys, and the Home Counties in the south of England. It sounds exotic now but, for an upper middle-class family in the postwar period, it wasn’t especially unusual. Wright didn’t follow the herd though: “My three years at Cambridge [where he studied Mechanical Sciences] were not spent usefully by attending lectures or studying.” Instead, he chased girls and discovered American literature, art house cinema, and the music of Dylan and Cohen. And Francoise Hardy, to whom Melody, the first of Wright’s three wives, bore a strong resemblance.

Wright’s career began with BRM, where the seeds of harnessing ground effect for race cars first started to germinate. On the subject of downforce, BRM boss Tony Rudd ‘s instruction to Wright was simple: “Use the whole car.” The story of how the alchemy of ground effect was exploited to create the Lotus 78, the car that Mario Andretti famously said was “painted to the road,” cannot fail to enthrall. I also smiled at the author’s recollections of how race car side skirts were evaluated, using Heath Robinson test rigs being punted around the Hethel test track in a Renault 4 van. There is also a fascinating account of how the different driving styles of Andretti, Peterson, and Stewart were recorded and evaluated. Nowadays data logging is accessible to even the humblest club racer but it was a sci-fi step into the future in the Seventies.

Wright’s career began with BRM, where the seeds of harnessing ground effect for race cars first started to germinate. On the subject of downforce, BRM boss Tony Rudd ‘s instruction to Wright was simple: “Use the whole car.” The story of how the alchemy of ground effect was exploited to create the Lotus 78, the car that Mario Andretti famously said was “painted to the road,” cannot fail to enthrall. I also smiled at the author’s recollections of how race car side skirts were evaluated, using Heath Robinson test rigs being punted around the Hethel test track in a Renault 4 van. There is also a fascinating account of how the different driving styles of Andretti, Peterson, and Stewart were recorded and evaluated. Nowadays data logging is accessible to even the humblest club racer but it was a sci-fi step into the future in the Seventies.

The author wryly admits that he has built eight houses but has only had six jobs. But there’s no need for modesty when those jobs included Managing Director of Lotus Engineering, Technical Director of Team Lotus, and President of the FIA Safety Commission. Unexpectedly, I found the account of the latter part of his career even more enjoyable than tales of his glory days in Formula One. The thing about Peter Wright is that he seems to have had an almost Zelig-like ability to become involved in the right stuff at the right time. Such as? The HANS device, Halo protection in single seaters, Euro NCAP (the road car safety testing regime), KERS energy recovery systems, and Balance of Performance regulations. Inter alia.

One-time FIA president Max Mosley rarely gets good press, especially after his death in 2021, but the author’s insights into a man he greatly admired reveal a much more nuanced personality than the lazy caricature of the Max & Bernie Show. And I confess I also didn’t expect to be reading about the safety philosophy of coal mining in South Africa, in which Wright became involved at the request of Professor Sid Watkins (FIA Safety and Medical Delegate).

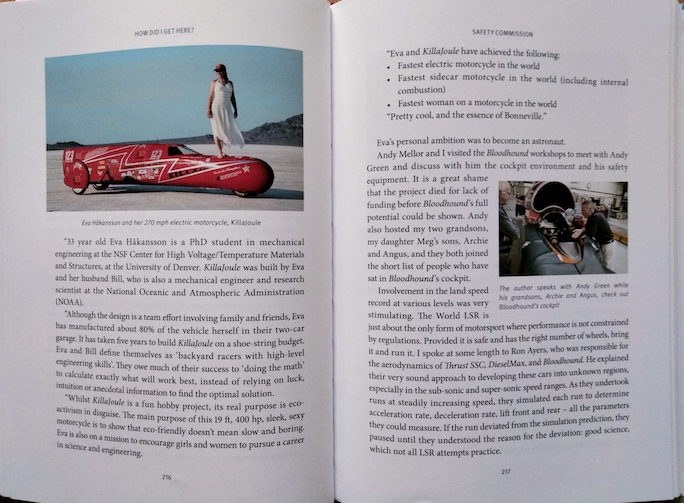

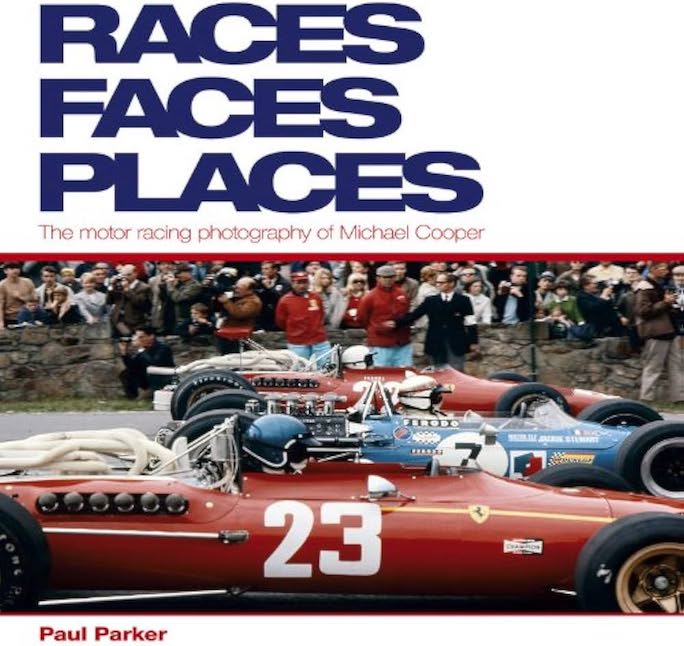

KillaJoule, the fastest electric motorcycle in the world.

The emphasis in the account of Wright’s professional life is the scientific and technical and, as is usually the case with engineers, he is anything but star-struck by famous drivers—there is little discussion of them. There has been much more to Wright’s life than the day job, because this is a man with endless curiosity and enthusiasm. He has had a lifelong love of flying, powered and unpowered, his personal life has been . . . I guess “lively” is the word (and, sadly, also touched by tragedy). He has ventured into communal living, blackcurrant farming (really), psychotherapy, and Tantra. In recent years he has become focussed on climate change. I can think of politicians on both sides of the Atlantic who would benefit from Wright’s concise and eloquent description of the cause and effect of man-made climate change. And as for motorsport’s survival in a world where the toxic legacy of fossil fuels has stimulated the growth of renewable energy: “There is no reason why F1 should not evolve to the role the horse has in racing: the basis for betting and the development of bloodline.”

The BBC has a long-running radio show called Desert Island Discs where guests choose eight pieces of music, one book, and one luxury. If I’m ever invited (as if), I do hope that Peter Wright enjoys my choices of music. He will need to, because this innovative and resourceful engineer is my luxury. I’m confident he’ll have air-conditioned accommodation built in a week and a solar-powered glider within a month. I just hope it’s a glider built for two.

Every student of motorsport history should read this book. It’s an absorbing and thought-provoking book from a relatively unsung hero of the sport and it deserves every success.

PS: Wright died in November 2025, age 79.

Copyright John Aston, 2024 (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter