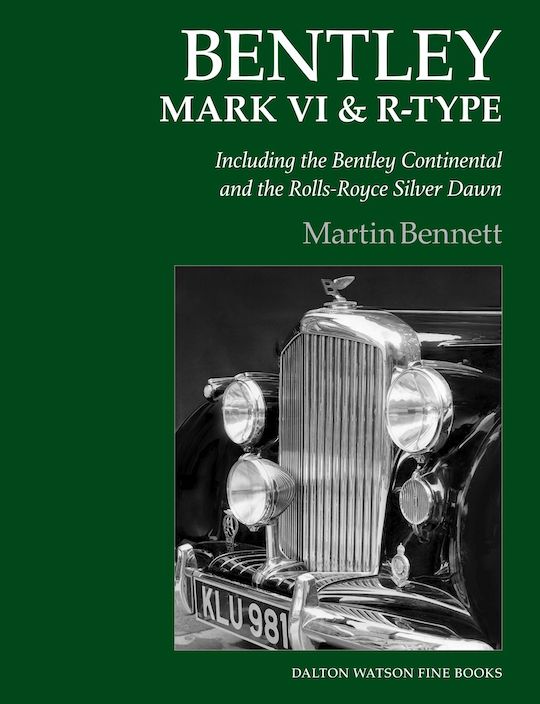

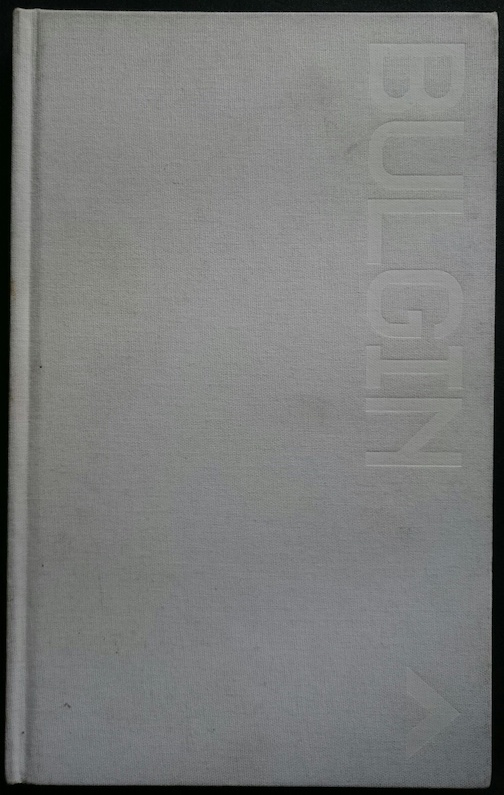

Bentley Mark VI & R-Type

Including the Bentley Continental and the Rolls-Royce Silver Dawn

by Martin Bennett

by Martin Bennett

Consider this volume the third in a Martin Bennett trilogy. In 2008 we were treated to a history of the Postwar Rolls-Royce Phantoms, 1950 to 1990—ending with the Phantom VI, the last Phantom built before the takeover by BMW. The Phantoms V and VI are regarded by many as the last of the truly classic limousines, and they are, occasionally, seen still in use, still regal. By many, they are considered the last of the cars built by classic coachbuilding methods.

2017 gave us an in-depth study of the Rolls-Royce Silver Wraith (1946–1958). This model was marketed as chassis-only; meaning chassis were sent to coachbuilders to be fitted with a body and interior. This third book delivers a deep history of the Bentley Mark VI and the Rolls-Royce Silver Dawn.

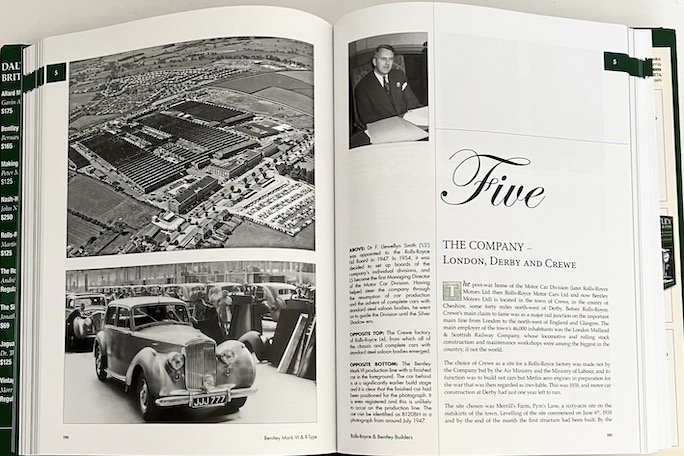

During World War II, the Rolls-Royce factory in Crewe, England, produced aero engines for military aircraft; after the hostilities the factory was refitted to produce motorcars. There was, however, a major change—a change some diehard traditionalists found appalling. Instead of the company supplying chassis to coachbuilders, as was done for the Silver Wraith and all prewar cars, Rolls-Royce began to manufacture complete units, producing the whole package at Crewe. The first model in this bold experiment was the Bentley Mark VI (1946–1952). A Rolls-Royce model came soon after, the Silver Dawn (1949–1955), also completed wholly at the factory.

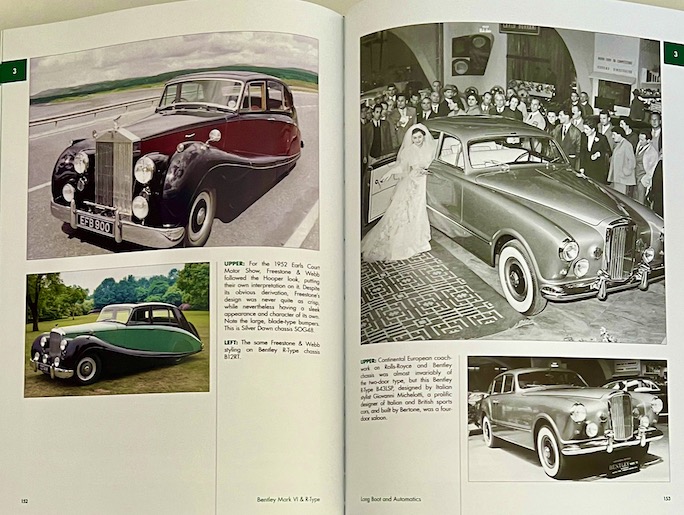

But there are complications. As the Mark VI and Silver Dawn were built as a body mounted on a rigid underframe, it was possible, as it was for the Silver Wraith, to transport the chassis to coachbuilders for, say, a more elegant or a more whimsical body. Also, the chassis was modified for the Bentley Continentals and coachbuilt bodies were also erected on this modified chassis. Bennett lists 38 plus 6 different coachbuilders who erected bodies on the 1,012 Mark VI chassis. The “plus 6” represents six unidentified coachbuilders. Complicated. This is but one example of the painstaking research involved in completing a book such as this one. Imagine the countless hours Bennett spent poring over factory lists, yellowing period magazines, club periodicals, vintage photographs, and older histories of the Rolls-Royce and Bentley marques. Sorting and arranging images. Fact checking—and rechecking. Bennett can surely be forgiven for his “plus 6”; the obscurity of these companies must be marrow deep.

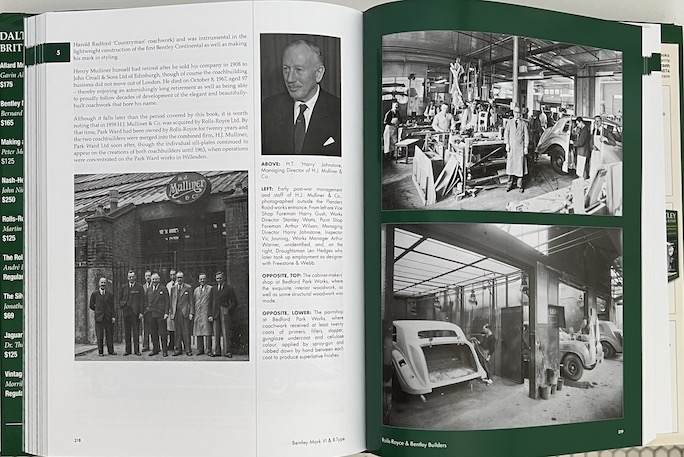

Illustrations: Although the many, many (mostly period) images of the cars delight and inform, the illustrations and photographs throughout offer so much more than the cars themselves. Illustrations and ads from discontinued publications; historic portraits of the company’s prime movers; designers’ sketches and completed drawings; engineering details from production manuals; and, my favorites, photographs showing factory personnel (along with a brief biography) and coachbuilders at work. Examining the shop photos, you may find yourself studying these craftspeople, in some cases not the first generation to work there. What was it like to be a part of this hallowed factory? Did they take pride in their part in the creation of these magnificent machines? Did they get a decent break for tea? And what of those troublesome images of painters working without masks? Smocks, vests, neckties.

Notes on the history of the company, pictures and facts concerning the prototypes and experimental cars, insightful information of the major coachbuilders (Hooper, James Young, Park Ward et al), mechanical specifications, details of the factory-provided toolkits and owners’ manuals, dated lists of various mechanical changes over the years—it’s all found in Bennett’s 392 pages. His happy appreciation for and overwhelming knowledge of his subject are woven throughout.

The book has three appendices and a handful of indices. The chassis list only gives the coachbuilt cars, a wise decision. Dalton Watson once again builds an attractive publication. Slipcase, dustjacket. Sturdy construction. Crisp pages and crisp fonts. Attractive layouts—I like the deep green border for the full-page illustrations. This third book in the series maintains the style and organization of the previous pair.

To end, a suggestion and a discloser: It would be good if Dalton Watson made their slipcases a smidgen taller in height. As it is, it becomes difficult to keep the dust cover from scraping or even tearing as it is slides into the slipcase. For users who wish to keep their books in mint condition, this becomes an irritation, especially as this book stands as an important research tool. The discloser is that I contributed photographs to Mark VI and my name is on the list of acknowledgements; I hope this doesn’t in any way attenuate the favorable flavor of my review.

Copyright 2025, Bill Wolf (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter