The Indy Car Wars

by Sigur E. Whitaker

by Sigur E. Whitaker

The book title brings to mind that other 30-year-long conflict, the 30 Years War among what was then known as the German States. The Treaty of Westphalia in 1648 may have brought an end to the open warfare associated with this devastating conflict, but it failed to end the hostilities and animosities that the war had generated on the continent. Peace did not come quickly nor easily in the years following the treaty. So, too, it could be said that while the reunification of Indy car racing in 2008 might have ended another war spanning thirty years of conflict, it too was also followed by a difficult, troubled peace. In her new book Sigur Whitaker bravely attempts to provide a narrative of this turbulent, challenging period of American national championship racing, better known today as “Indy car racing.”

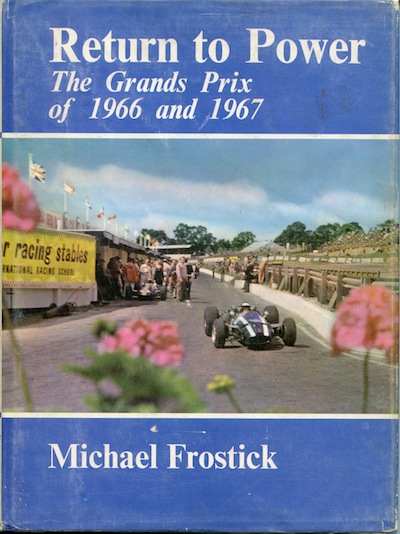

For decades upon decades, the International 500 Mile Sweepstakes race held annually at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway on Memorial Day was perhaps the largest single-day sporting in the world, to say nothing of the United States. By the 1970s, it was not unusual for over 100,000 spectators to attend the first day of qualifying, with several times that number showing up on race day. The Indianapolis 500 was the premier automobile racing event in the US, overshadowing even the United States Grand Prix and the Daytona 500 in terms of attendance and prize monies offered. Yet, nowadays the number of spectators attending the first day of qualifying at the Speedway is, at best, measured in a few thousands, not the tens of thousands of days now long past. While the attendance at the Memorial Day race in Indianapolis is still huge compared to other automobile races in the United States, it is clearly down from former years.

With The Indy Car Wars, Whitaker, the great-great-niece of Speedway founder James Allison, provides us with a narrative chronicling the decline of Indy Car racing from the latter years of the 1970s until the 2014 season. She begins her tale with the deaths in October 1977 of Anton “Tony” Hulman (who bought the Indianapolis Motor Speedway [IMS] in November 1945; Whitaker has written a bio of him, Tony Hulman, The Man Who Saved the Indianapolis Motor Speedway) and then the eight members of the United States Auto Club (USAC) who were killed in an airplane crash in April 1978. By the time she ends The Indy Car Wars, Whitaker has guided us through: the revolt of the car owners in 1978 and the formation of the Championship Auto Racing Teams (CART), its various internal struggles and eventual demise at the end of the 2003 season; the pushback against CART by the IMS; the creation of the Indy Racing League (IRL) by Hulman’s grandson, Tony George, in 1994; the eventual reunification of Indy car racing in 2008; and then winding up with a look at what is now the Verizon IndyCar Series at the end of the 2014 season.

It is a tale that dwells on an aspect of automobile almost entirely ignored: what is usually known as “racing politics” and a topic that is generally considered to be an anathema to racing fans. That The Indy Car Wars is a book devoted entirely to racing politics and most of the Who, What, When, Where, Why, and How of the 30-year struggle—often simply referred to as “The Split”—that still continues to affect Indy car racing today, is rather remarkable. That it has taken this long since reunification for something such as this book to appear is, on the other hand, not so surprising. It would seem that few within the ranks off those interested in Indy car racing either have much in the way of any interest in the topic or simply that “The Split” is not the sort of subject matter for which there is much of a market. It is, perhaps, a combination of both of these.

Whitaker’s major sources for the book tends to be material from National Speed Sport News (Chris Economaki, Ron Lemasters, Jr., and Steve Mayer), and the Indianapolis Star (Steve Ballard, Curt Cavin, Bill Koenig, and Robin Miller), along with material gathered from several Internet sites such as Crash.net and the Indiana Business Journal. As such, it presents what could perhaps be considered as a somewhat edited version of the “first draft of history.” That Whitaker has provided that rarity of rarities in a book on automobile racing, endnotes, allows the reader to see exactly where she found her material. Whitaker mines this material well, providing one of the few coherent accounts of the often-bewildering succession of the various boards and their memberships that were created and reorganized during the decades of conflict. One wishes, however, that she had reached beyond these very select sources for more on “The Split.”

Among the several quibbles regarding The Indy Car Wars, it is the mention of the “V-4 Offy” (pp. 12/13) that fairly leaps out at the reader in the early going, something which threatens her credibility to the diehard racing fans and which should have been caught with better editing. Fortunately, this is one of the few such major gaffes.

It is almost a certainty, given the level of animosity that still lingers, that those in the various camps that still divide Indy car racing will accuse Whitaker of bias. I would offer that The Indy Car Wars does a very credible job of laying out the basics of the thirty years of warfare within the sport, striving to provide us with as objective a narrative as possible by chronicling the many twists and turns in this often depressing tale. One hopes that others will follow Whitaker’s lead and give this topic more attention, especially since she has now paved the way.

Copyright 2016, Don Capps (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter