100 Years of Legends, The Official Celebration of the Le Mans 24 Hours

by Denis Bernard, Basile Davoine, Julien Holtz & Gérard Holtz

by Denis Bernard, Basile Davoine, Julien Holtz & Gérard Holtz

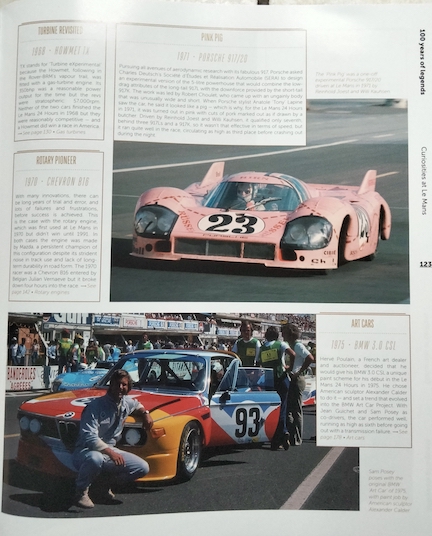

“A journalist asked me about the engine. I replied ‘It doesn’t have an engine, it runs on color. Are you aware of the dynamic power of color?’”

—Hervé Poulain in 1975, on the BMW 3.0 CSL art car painted by Alexander Calder

Schoolmaster Mr. Gradgrind is the chief villain in Charles Dickens’ Hard Times, and his stern words are the opening lines: “Now, what I want is Facts. Teach these boys and girls nothing but Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant nothing else and root out everything else.” This book is one Mr. Gradgrind might have written if endurance racing had been his thing. Because this 336-page blockbuster is so laden with facts that it risks overwhelming any reader who reserves head space for any subject other than the race that celebrated its centenary in 2023.

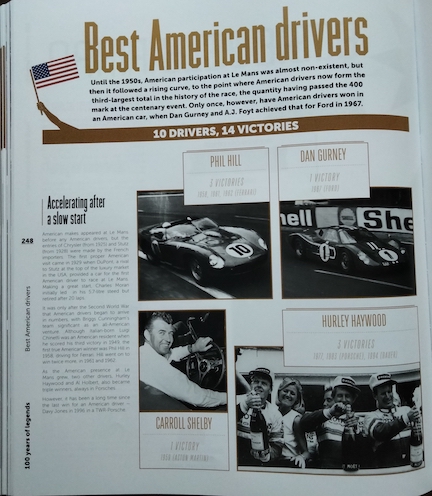

Typical busy page layout.

The book describes itself as “an official celebration” and the (four!) authors have decided that the way to get the party started was to write a book with no fewer than 122 chapters. There is no central narrative thread per se but instead one chapter follows another in what appears to be random order. Thus an interview with Seda Gregory, widow of 1965 victor Masten, appears between chapters covering “100 years of time keeping” and “Fuel.” Go figure.

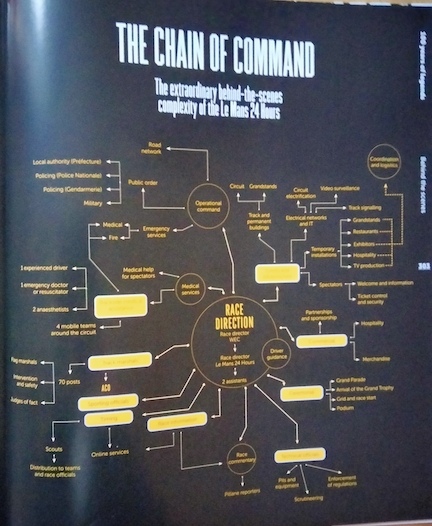

The book is a high-quality, dustjacket-free hardback in Evro’s trademark style, and it succeeds in giving the impression that if Mercedes published books, they’d feel like this one. There are countless illustrations, and the layout is busy, almost frantic in its determination to impart as much information as possible. There is a veritable blizzard of diagrams, graphs, and flow charts on the myriad facets of the world’s most important motor race (despite competing claims from the other two prongs of the sport’s Triple Crown, the Indy 500 and the Monaco Grand Prix). There is a price for this sort of wide scope and that is a sometimes superficial approach to subjects that really merit greater coverage. The desire to cram in so much information also comes at the cost of legibility as the font (small and faint) was a challenge to this reviewer’s eyesight.

One of many diagrams, this one is about who does what in staging the race.

But if you treat the work as more scrapbook than textbook, to be dipped in and out of on a whim, it will certainly satisfy Le Mans aficionados’ appetites. TLDR* is not an accusation you can level at this book, and any reader unfortunate enough to live with ADHD** will not be troubled, as no subject survives for long before being supplanted by another, often unrelated topic. Given the book’s span, and its multiple authorship, it is hardly surprising that there is some repetition, and I counted five references to the 405 km/hr Mulsanne speed record set by Roger Dorchy’s WM Peugeot in 1988.

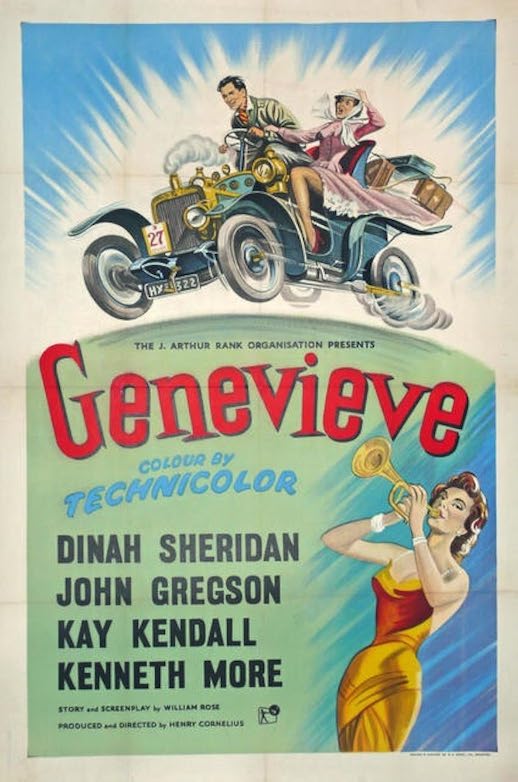

Many books about Le Mans concentrate on the great races, to the exclusion of almost everything else. But we know the legends almost by heart already—from Ford’s failure to stage a dead heat in 1966 to Ickx/Oliver’s tiny margin of victory in 1969 and the dashing Bentley Boys’ victories almost a century ago. This book rightly mentions them but, refreshingly, it doesn’t really dwell on them. It is the peripheral stuff that intrigues, such as the evolution in headlight performance and the story of the medics and marshals who are the sine qua non of the event. And while Audi’s domination and Ferrari’s glory days aren’t neglected, I found myself more interested in the chapter called “Curiosities at Le Mans.” Who could fail to be charmed by the eccentricity of the catamaran Nardi Bisiluro, intrigued by the gas turbine Howmet TX, or seduced by the series of art cars that started with Hervé Poulain’s Alexander Calder BMW CSL?

Curiosities at Le Mans: Porsche 917 Pink Pig and BMW CSL Art car with Sam Posey.

Motorsport has been addicted to nostalgia since 1998, when the first Goodwood Revival triggered a seismic movement in the sport’s focus. Not a month passes without yet another glitzy retrospective, salon privé, or historic festival celebrating somebody or something’s (often contrived) anniversary. But Le Mans has earned the right to celebrate its heritage more than any other event and, as we learn from the book, its management team are a canny bunch, knowing how to look forward as well as back. Nothing illustrates this more eloquently than the Garage 56 innovation which made its debut in 2014. Since then, the CDNT (“Car Displaying New Technologies”) has showcased a succession of extraordinary projects, from the left field Nissan Deltawing to the SRT 41 team’s achievement in enabling quadruple amputee Frederic Sausset to compete in an adapted Morgan LMP2 prototype, finishing in 38th place in 2016. And I’m not sure whether it was the ACO’s sense of humor or taste for irony that was responsible for 2023’s Garage 56 occupant, a full fat NASCAR Camaro? Innovation though? Maybe not so much, huh?

Vanina Ickx inherited her dad’s race DNA.

There is one elephant in the room, and that is the failure of the book to properly cover the 1955 accident that killed 82 people and injured many more. There are several references to the disaster, but all are made en passant and I think that almost to airbrush the accident out the race’s official history is a serious failing. The accident was the worst in motorsport history and it didn’t just change Le Mans forever, as its wider repercussions were felt throughout the sport. I did not want a ghoulish, sensationalist account but I did expect a dispassionate summary of what happened, and why. It seems to me to be disrespectful to the victims, not least because so many of them were from local families. Richard Williams’ 24 Hours, 100 Years of Le Mans demonstrated how this difficult subject can be handled with sensitivity and empathy.

This book has been expertly translated from its original French and will provide rich pickings for the thousands of Le Mans fans who make the pilgrimage to the Circuit de la Sarthe every summer. It will furnish them with an embarrassment of riches, enough material for a full 24 hours’ worth of automotive Top Trumps. It’s rather too rich a meal for a Le Mans dilettante like your reviewer, whose only experience of the place was an off season visit, highlighted by a 100 mph blast down the Mulsanne in a Fiat Uno Turbo. But now I know that my little bolide was far from the slowest car to have driven down the RD338. I’d wager 50 old francs that the class-winning Simca Cinq, packing all of 558 cc, might have struggled to keep up. It averaged 52 mph in 1938, bless it.

- *TLDR –“Too Long, Didn’t Read” (internet acronym)

- ** ADHD – Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

Copyright John Aston, 2023 (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter