Mustang: An American Classic, Yesterday – Today – Tomorrow

by Michael Mueller

by Michael Mueller

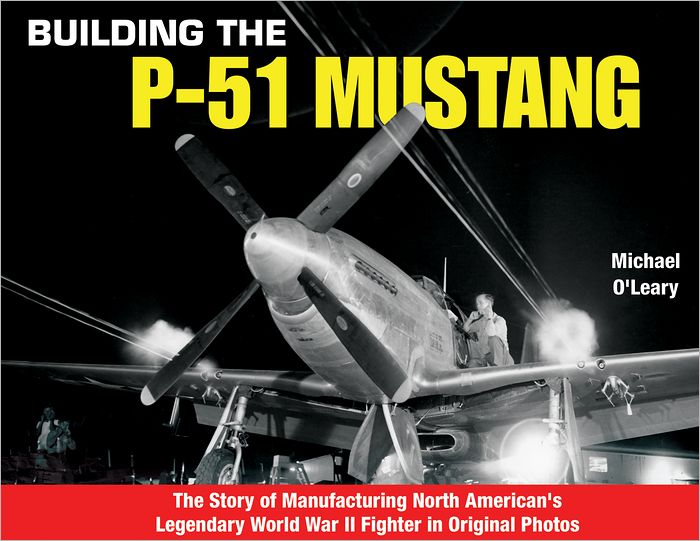

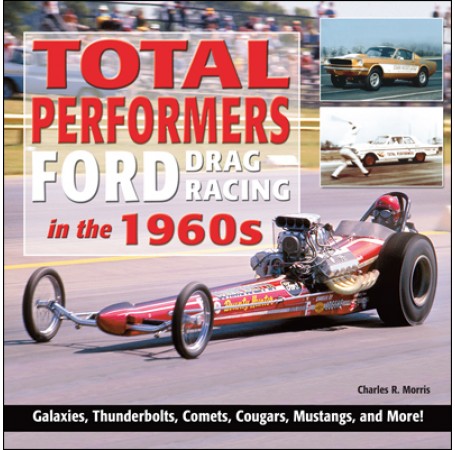

Ford’s Mustang may have been the quintessential pony car but there is nothing pony about this oversize book—at over 14″ tall it will tower over most anything else on the bookshelf. Published in 2009, this lavish production is sort of a 45th birthday tribute to a wildly successful car that by then had sold about 9 million copies, had remained in uninterrupted production since its otherworldly spectacular debut in 1964, and been the model to cross the million-units-sold threshold quicker than any other American car.

“You do the math: 1945 plus 16 equals what? An army of young buyers just reaching legal driving age as the ‘60s dawned, that’s what.” Seems so obvious—but Ford Division’s freshly minted General Manager Lee Iacocca—himself only 36 years old and possessed of entirely different reference points than his rather stodgy predecessor Robert McNamara—was one of only a few to see the light when he floated the idea of a “youth” car that not only would cater to a younger buyer but would also be more gender neutral than any previous Ford so as to be appealing to the female buyer.

This is the context for Mueller’s story. Having written two years prior to this one the well-received Complete Book of Mustang (MBI, ISBN 9780760328385) he has a firm grasp of the nuances and details. That book had been created “in cooperation” with Ford Motor Company and this new one bills itself as “officially licensed.” Keeping the aforementioned birthday angle in mind it is fair to say that the new book encircles its subject in a different way. Photographs take pride of place—as one should expect, considering the book’s size—whereas the story arc and degree of magnification are somewhat condensed (no specs or the like, for instance). This observation is not to be taken to imply a deficiency; it is merely meant to explain the differences between two books by the same author that followed each other closely and cover the same topic. Especially those photos that take up the full spread (22″) are, in fact, so large that one is often inclined to hold the book at arm’s length just to get some distance, or to put down the book on a table and take in the photos from a couple of feet away. A nice “problem” to have . . .

FoMoCo cooperation is certainly evident in the masses of illustrations from company archives. Moreover, many of the car photos are from period promotional brochures; they may thus not be new to the record but they are good photos and show the cars to their best advantage. Each of the eight chapters ends with pages and pages and pages of photos. So as to not diminish their visual impact these photos are not individually captioned but are instead preceded by a bundled set of brief captions. Everywhere else the photo captions are rather more extensive, printed right next to the corresponding photos, and more or less specific to what the image shows, highlighting tell-tale features or design and construction details etc. Presenting period photos and ads also conveys a specific sense of time and place in terms of lifestyle, fashion, and color.

That the book takes an unabashedly pro-Mustang stance is surely not bias on the author’s part but rather conviction and enthusiasm. His engaging way of writing will instill the same in the reader. He knows the bigger picture well enough, having written for Corvette Fever just the same as for Mustang Monthly—and Muscle Car Review, Collectible Automobile, Street Rodder, Automobile Quarterly and others as well as a string of lifestyle magazines.

Nothing that is truly relevant to the Mustang story in terms of people, trends, design, marketing, competitors, and philosophy is missing. In keeping with the book’s purpose, little is said about manufacturing, plants, specs etc. All models and variants are covered, in chronological order and with much attention to the plethora of running changes. Racing and various other peripheral subjects (cf., Thunderbird, Steve McQueen’s “Bullitt” Mustang, SVT cars, bios) are dispensed with in the form of sidebars. The book ends with a 1960–2009 timeline and a fairly deep Index that also lists each model by year. Perhaps rather more could have been said about engineer/product planner Donald N. Frey whom Time magazine in 1967 called “Detroit’s sharpest idea man.” Despite his many subsequent achievements in other sectors, Mustangers hold him dear for running the prototype styling and development in a record 18 months and under anything than ideal conditions. He himself never lost his affection for the car and still owned an original Mustang at the time of his death in March 2010 at age 86.

At one point J Mays, who’s been Ford’s Group Vice President of Global Design and Chief Creative Officer since 1997, is quoted as saying: “Mustang attracts two kinds of drivers—those under 30 and those over 30.” This book will give you a good understanding of what’s behind such universal appeal.

And do take a look under the dust jacket!

Copyright 2011, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter