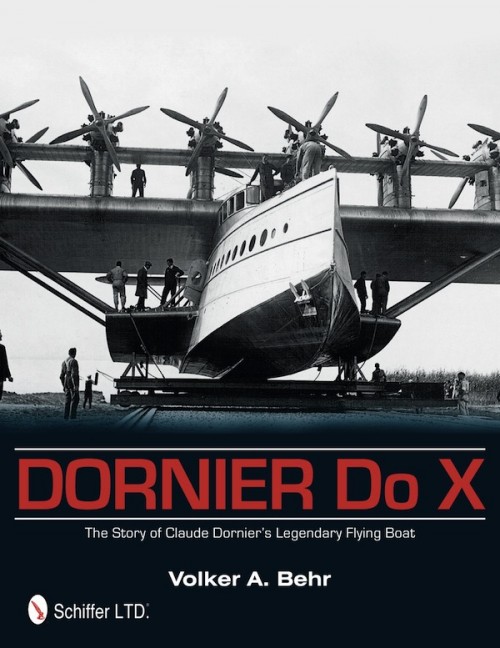

Dornier Do X: The Story of Claude Dornier’s Legendary Flying Boat

“It took the steamship almost seventy years to reduce the travel time between the two continents by half. You just can’t expect aviation, in its youth, to overcome the enormous space of the oceans. The first step has been made. The preconditions for lasting success have been met. The flying boat is here.”

—Claude Dornier

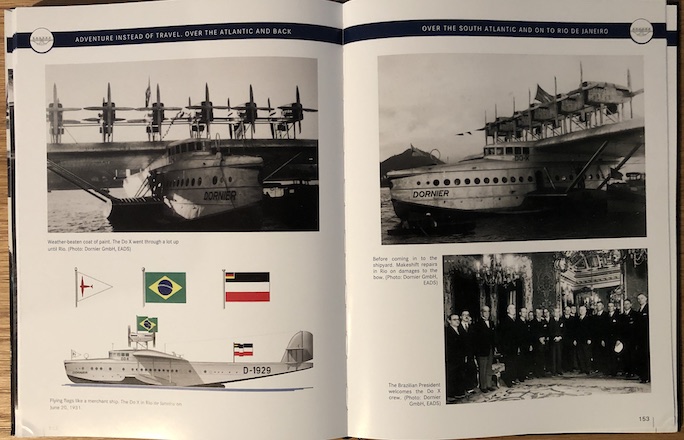

Ah, yes, “lasting success” . . . it didn’t even remotely work out that way, not for Dornier and not for anyone else who bet on seaplanes. The first of his only three Do X’s took to the air in 1929, and by 1936—three years after having been decommissioned already—was mothballed in a museum. The other two went to the scrapper a year later. And even though his airliner was the first to cross the Atlantic, in 1931 and with multiple stops, by 1938 that too was sooo yesterday when a Focke Wulf Fw200 became the first aircraft to not only fly nonstop from Berlin to New York but operate from land bases. The seaplane no longer had an advantage. That both of these aircraft were of German manufacture only underscored that this country’s aviation industry had the chops to play on the international stahe.

The few meaningful books on this remarkable aircraft were published to commemorate the 50th and 75th anniversaries (1979, 2004), meaning they came out came out many years apart. Things have improved in recent years, with another one in 2006 and then this book, first published in German in 2011 (Motorbuch Verlag, ISBN 978-3613033290).

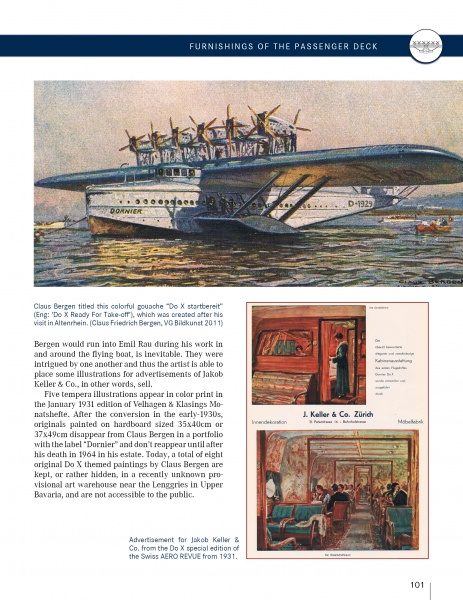

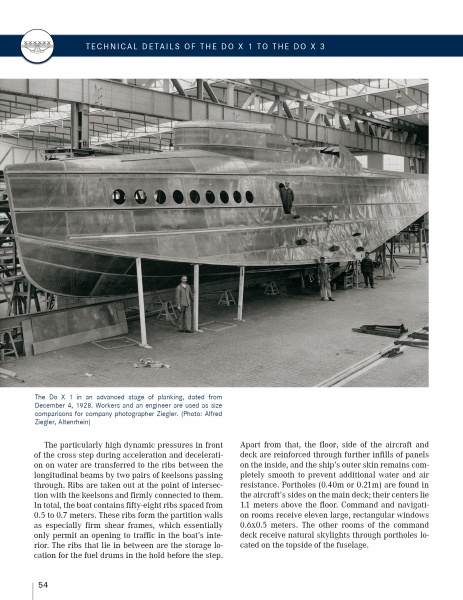

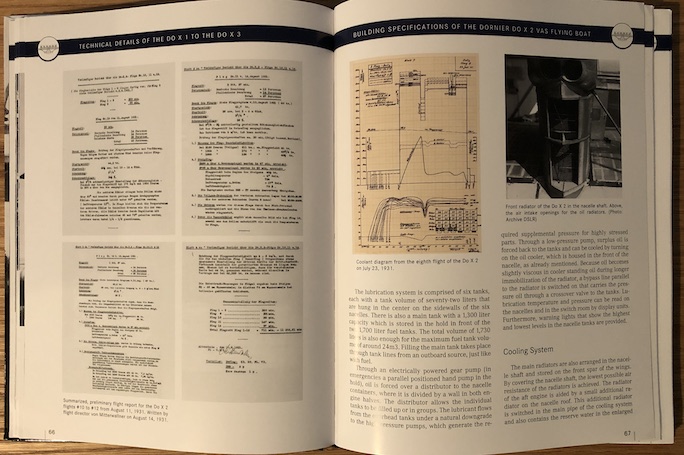

They all have a different focus and complement each other but this one is also the first to draw on archival material that was not available to the others. The reason for this is that Dornier kept two complete sets of records, one in Germany where the planning took place and one in Switzerland where the actual construction happened. The former had been lost in the war and the latter only came to light (or were made available to the public) in recent years, most especially the photos by company photographer Karl Alfred Ziegler, many of which are shown here for the first time.

Thanks to those dupes in the Swiss archive, such primary sources as flight test reports and interior design studies or financial statements and even menu cards can now be presented to a public eager to learn more about this ambitious project.

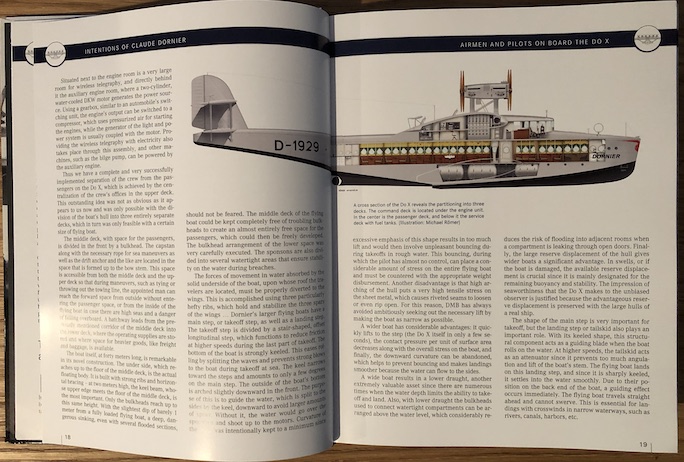

In its day, the Do X was the largest, heaviest, and most powerful flying boat in the world. Three decks, 6 pusher and 6 puller engines, 14 crew and 70 passengers (test flights were done with as many as 170), an industry-first hollow metal fuselage . . . the list of staggering statistics is long indeed. Dornier, who had started as a Zeppelin designer, recounts that the man whose name is synonymous with airships, Count Zeppelin, was among the few who admitted the limitations not only of the airship but also the airplane. A flying boat was needed and, said Dornier in 1937, “He chose me to fill this gap . . . There are few who know about this and that is why it should be said here.”

Behr has spent many years on this subject and so is able to speak to all aspects of the Do X in great detail and seeming ease, whether it’s the innards of the engines or the china patterns. He also addresses political and economic factors pertinent to the Do X era. Considering that this was the pinnacle of and standard-bearer for German engineering skill, the reader will probably find that it is not fully exhausted why so few examples were built and why two of the three went into Italian service. The three examples had different specs, and those are covered. Both the technical achievements and the shortcomings are examined, as are the various accidents that beset the small fleet. Reports from pilots and crew as well as passengers give good accounts of what it was like to operate and experience this ocean liner of the air.

Behr has spent many years on this subject and so is able to speak to all aspects of the Do X in great detail and seeming ease, whether it’s the innards of the engines or the china patterns. He also addresses political and economic factors pertinent to the Do X era. Considering that this was the pinnacle of and standard-bearer for German engineering skill, the reader will probably find that it is not fully exhausted why so few examples were built and why two of the three went into Italian service. The three examples had different specs, and those are covered. Both the technical achievements and the shortcomings are examined, as are the various accidents that beset the small fleet. Reports from pilots and crew as well as passengers give good accounts of what it was like to operate and experience this ocean liner of the air.

The excellent text is made more powerful by the great number of illustrations, all superbly reproduced and large-size, some in color.

The excellent text is made more powerful by the great number of illustrations, all superbly reproduced and large-size, some in color.

On the plus side, the book is very nicely designed in a crisp blue-and-white scheme echoing the colors of the German national airline. On the negative side, the English version is, to say the least, poorly translated and further hampered by erratic punctuation and highly irregular hyphenation.

Of all the Do X books, this is the most wide-ranging. A FAQ-style closing section addresses minutia such as why there’s an “X” in the type designation or why this aircraft is referred to as a “he” and not a “she.” A three-page Bibliography list Behr’s sources and related literature. There is no Index.

Copyright 2020, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter