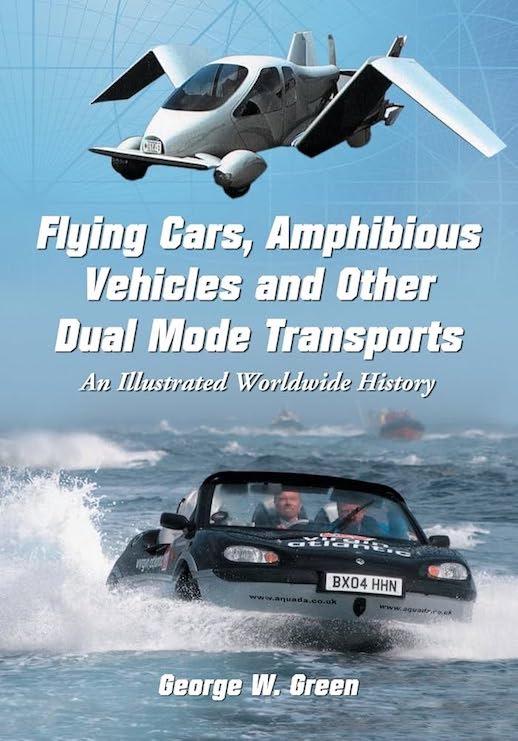

Flying Cars, Amphibious Vehicles and Other Dual Mode Transports

An Illustrated Worldwide History

by George W. Green

This book lists just about everyone from 1900 to 2010 who has ever publicly stated an intention to build either a flying car, a car/boat combination, or any other land/sea/air multi-use vehicle. Author George Green briefly summarizes what is known about each effort and in rare cases, its success or failure. The Bibliography lists 286 sources from which the information for the book was drawn; 224 of these are magazine articles from Motor, Motor Age, Road and Track, Flying, Popular Mechanics, Popular Science, American Heritage, Elks Magazine, and many others. As a result, the book reads like an uncritical summation of what was originally published without much analysis. A lot of boyhood-dream sort of thinking is presented along with examples of serious private and corporate prototypes that rarely make the leap from concept to reality.

Mixed in with the long list of failed dreams are examples of successful prototypes and mass-produced commercially viable vehicles like the 3,300 Amphicars (car/boat combination) manufactured by Hans Tripel in Germany between 1960 and 1968. At one time sold here in the US by 118 dealers (President Johnson purportedly used one on his Texas ranch), the vehicle is now an increasingly valuable collector car supported by an active club. Also interesting are all the famous aircraft, automobile, and industrial designers who at one time or another tried their hand at creating a flying car or other combination including Glenn Curtiss (flying car prototype), William Stout (Skycar prototype), Alex Tremulis (flying car design), Bert Rutan (flying car design), Norman Bel Geddes (helicopter bus concept), Sir Alec Issigonis (amphibious trolley), science fiction publisher Hugo Gernsback (counter-gravitational gyro dream car powered by atomic energy), and Ferdinand Porsche (1940 military Schwimmwagen). Although not mentioned in this book, during World War One Ferdinand Porsche also designed and manufactured a clever hybrid road/rail train of linked supply wagons with electric motors in the wheels capable of traveling on surface highways, or on existing German railroad lines. Everyone, it seems, from famous to obscure, has been intrigued by the challenge of designing a dual-mode vehicle.

Two rare examples of successful contemporary designs are displayed on the book’s cover: the Terrafugia, Inc. flying car Transition designed by MIT aeronautical engineers, and the Aquada amphibious sports car from Gibbs Technologies in the UK. Although both machines employ proven technologies, neither is currently being mass-produced. Both companies are waiting to accumulate the funding needed to get into serial production—the fate, it seems, of most dual-mode vehicles ever designed other than vehicles manufactured for the military and funded by the needs of war (DUKW and Schwimmwagen-type amphibious troop transports that all major military powers developed during World War Two). The lone examples of commercially successful designs are the aforementioned Amphicar (no longer produced), and the small off-road six-wheeled swimming ATVs currently manufactured in Buffalo, New York by Recreatives Industries, Inc. Several other companies manufacture specialized land/water vehicles in limited numbers, but the lack of federalized safety bumpers and airbags keep them off US highways.

On the downside, the brief vehicle descriptions that author Green lists for us are frequently too short to be useful. Some examples: “The Japanese have an amphibious sightseeing bus, fueled by cooking oil.” “In 1955 Charles Pritchard designed a stub-wing craft.” “In 1961 the SeaGeep was developed and tested.” There are also many examples of what I call “logic typos” where what is claimed is probably not correct: “. . . overall length 15.5 ft., wingspan 225 ft. and the car width 4 ft.” “. . . a foldable main wing and a secondary left wing.” In 1917, Green tells us, George Monnot’s car/boat combination “did 25 mph on land and 89 mph in the water.” Or that Frank Rinkerknecht’s 2004 Rinspeed Splash was capable of “speeds of up to 125 mph on land. As a boat the pop-up, three-bladed propeller takes it up to 150 mph. . . . The engine: 750 cc running on natural gas.” In view of the laws of physics, none of these claims seem plausible to me, but are listed as fact, casting doubt on the veracity of the rest of the data contained in the text. Reader beware.

The book is divided into six main sections: Road-Air Vehicles, Amphibious Vehicles, Road-Rail Vehicles, Water-Air Vehicles, Other Dual Vehicles, and Triphibious Vehicles. Acknowledgments and an Introduction begin the book, with a generous Glossary, comprehensive Bibliography, and a long Index closing things out. The author is a World War Two Army veteran, retired automotive industry executive, university instructor, transportation historian, lecturer, and photojournalist. While the book may be useful as a raw unedited listing of dual-mode vehicles, it is rarely informative enough to be helpful beyond its sourcebook format.

Copyright 2011, Bill Ingalls (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter