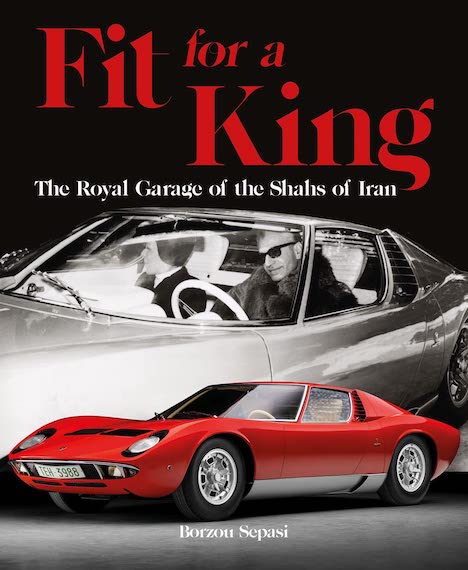

Fit For A King, The Royal Garage of the Shahs of Iran

by Borzou Sepasi

by Borzou Sepasi

with Ramin Salehkhou and Gautam Sen

“. . . This does not mean that the process was not fraught with problems. Not only were there the usual problems of bureaucracy and red tape, but also the fact that four decades after the revolution, there is still much sensitivity about the rule of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. Many times I was faced with suspicion as to why I was gathering these materials, only to assuage all by showing the documents and information that I was gathering for this book, and that all my efforts were for a strictly non-political historical project.”

Let’s start . . . here: “This is not a political book.”

Why even say that, in a book that appears to be about cars? Those words are found in the first of two Forewords, and making such a statement shows that the writer (Long Live Nick Mason!) is not afraid of addressing the elephant in the room: the entirely uneven 38-year-long rule of the main protagonist of this book, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the last Shah of the Imperial State of Iran. It’s fine and dandy to have the keys to a hundred, two hundred cars but when your people start trying to assassinate you, depose you, run you out of the country, you probably did something, ahem, problematic. And if it says King of Kings on your calling card, chances are it was political.

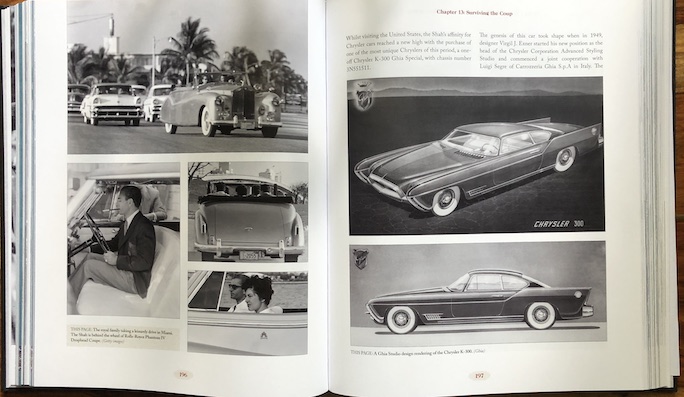

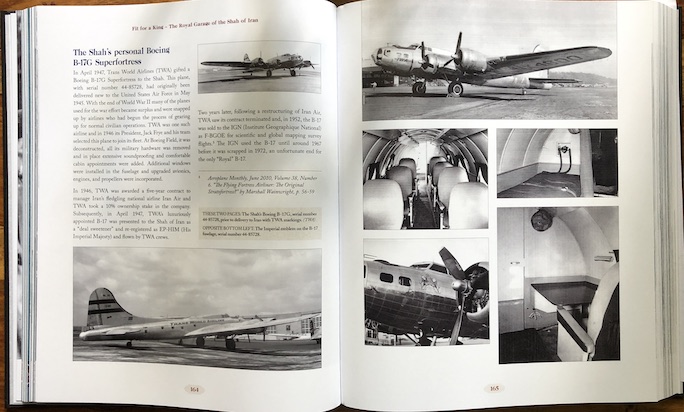

So, if you are a student of world history, or lived through the mid-1970s oil crises this particular king triggered, you will have to put a lid on all you know lest it get in the way of simply learning about Reza Pahlavi’s really quite stupendous collection of cars. That he had one should not, however, be taken to mean he was an intentional, discerning, connaisseur-type collector—he did know what he liked, and he had seemingly bottomless wealth at his disposal (thanks, inheritance; thanks, oil) but much of the stuff simply found its way to him because of the office he held: yachts, trains, planes, carriages, palaces and all manner of other paraphernalia, much of which is covered here.

It’ll help to know that the author is Iranian himself (b. 1978), a fact that opened doors that would have remained closed to anyone else. Also, and crucially, it allowed him to recognize bits of primary information (cf. correspondence, documents, and the like) in the archives of the royal garages that add layers of heretofore unknown or undocumented detail. Even among his countrymen, Sepasi was the first private citizen to be granted access to the various post-revolution (quasi-) government entities among which the Shah’s “stuff” was dispersed. While the book jacket does tell you that Sepasi has published two books already (2012 and 2016) and been a long-time magazine contributor, it does not tell you that in 2008 he was recognized as Iran’s premier automotive writer (or that he was and is professionally active in managerial capacities in various automotive endeavors).

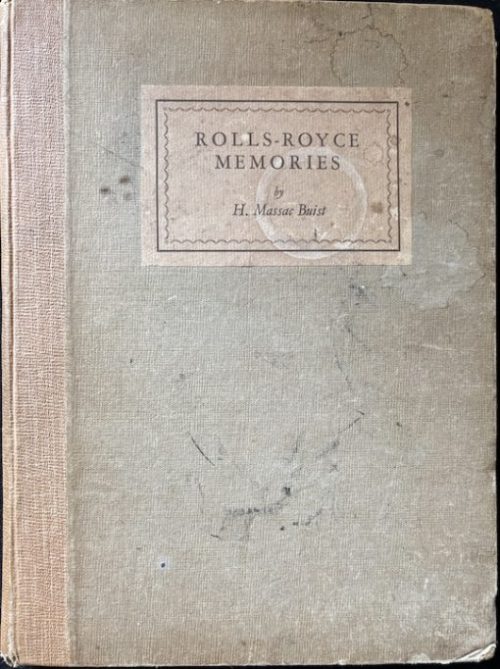

Rolls-Royces obviously figure prominently as state cars, and most particularly this Phantom IV whose breakup to this day confounds historians.

The 2016 book, titled Iran Royal Garage and self-published in Farsi only, is for all practical purposes the forerunner to the present book; it won that year the SAH’s Nicholas Cugnot Award in the “Language other than English” category.

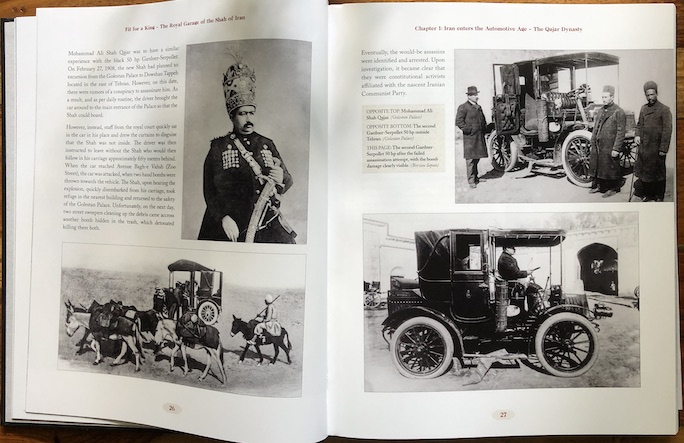

If all you know of Iran is what you glean from today’s news, prepare to have your horizons broadened. The book title talks about kings, plural, so the author dials the clock back a ways. Iran’s monarchial history is much older than that of the car so the book begins with the ruler who brought the first motorcar into the country, and describes how motorization took hold in the private and the industrial/military sphere. A good third of the book is devoted to Big Picture context and backstory.

While young Reza, then the Crown Prince, makes an appearance as early as chapter 4 (“In His Father’s Footsteps”) it’s really not until chapter 11 (of 35) that the narrative firmly focuses on his cars. To appreciate young Reza’s interest in cars, realize that he was allowed to learn to drive when was ten and sent car-shopping when he was thirteen, choosing a stupendously expensive Hispano-Suiza J12 bodied by Saoutchik (chauffeur-driven, just to be clear).

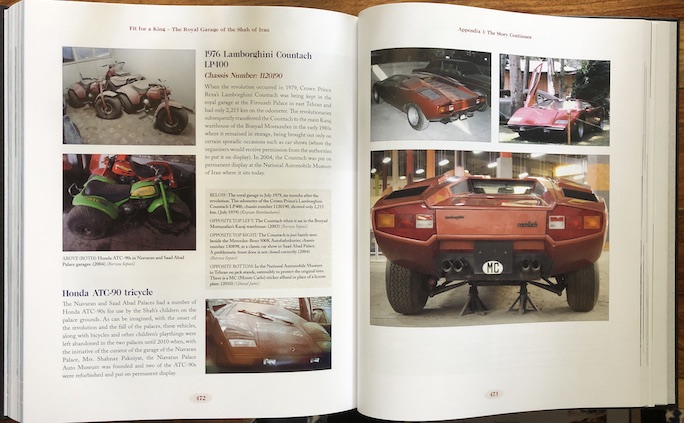

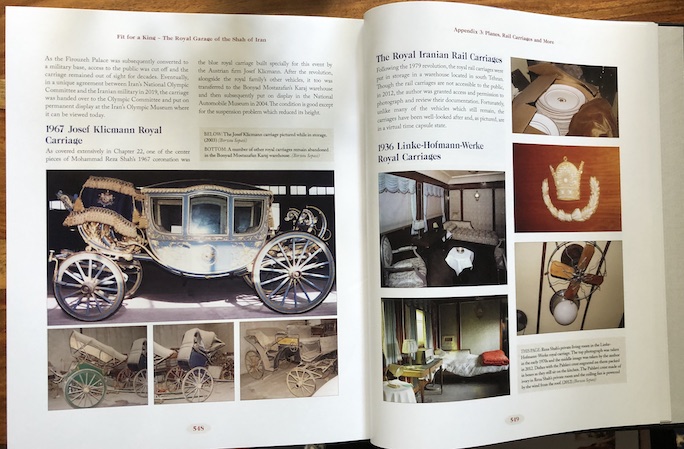

The book progresses in chronological order so the cars make their appearances when and where they intersect with the story. There is no general-purpose Index but there is a listing (called an Index; in microscopically small type, as is the Bibliography) at the back of the book listing the cars and other types of vehicles in alpha order along with year, chassis no., notes and, importantly, page references. Appendix 1 is an 80-page-long detailed description of (certain, not all) cars in their as-found state and post-revolution disposition.

An example from Appendix 1 that shows vehicles in as-found condition.

On the one hand there is an enormous amount of detail (and footnotes right on the pages on which they care called out) brought together here, on the other hand there are occasional lapses that will confound anyone who will want/need to use this book as a proper reference tool. One example: an entire chapter is devoted to “House Cleaning in the Royal Garage” (of interest because it put cars into private hands) but it gives no date and elsewhere in the book the event is referred to as both “1957” and “1959.” It could have been a prolonged undertaking that spanned several years—but it could also be a research/writing/editing glitch, which, however minor, is never worth the confidence-eroding consequences.

It will surely take multiple attentive readings to fully absorb everything this book offers. Considering that there is no other like it, don’t ignore it.

Won the OVERALL WINNER category at the 2022 RAC Motoring Book of the Year awards.

Copyright 2022, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

I agree that this is an important book but cannot accept the claim that Reza Pahlavi triggered the mid-70’s oil crises – I prefer to point the finger at the Club of Rome. Let’s now get on with reading the book.