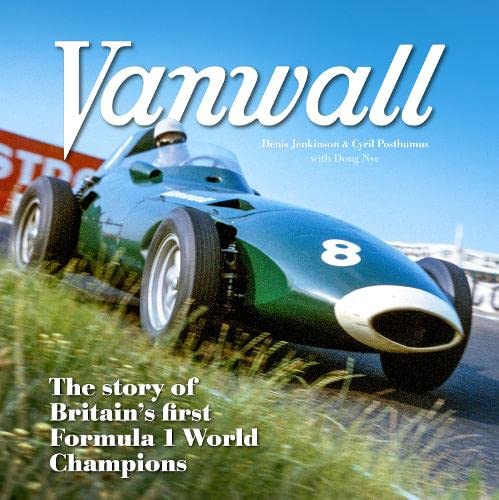

VANWALL, The Story of Britain’s first Formula 1 World Champions

by Denis Jenkinson & Cyril Posthumus, with Doug Nye

by Denis Jenkinson & Cyril Posthumus, with Doug Nye

“Tony Vandervell . . . lit the torch that Cooper, Lotus, BRM, Brabham, McLaren and others took up and held high ever since”

—Messrs Jenkinson and Posthumus

Terms and conditions apply: my interest in Grand Prix racing was sparked in 1967, and with the arrogance of youth I airily dismissed everything that preceded the 3L formula in Formula One as ancient history. Half a century later, I may have mellowed but I still have no more than a polite interest in pre-1960 racing, meaning that this impeccably researched book is being reviewed by a dilettante, if not an impostor. But perhaps my relative ignorance can give me a perspective that a closer acquaintance with Fifties’ racing might have denied me?

This is a brilliant book. The text is forensically detailed, the ephemera intrigue and delight, and the pictures . . . those gorgeous pictures . . . they just enthral. If this book were a car, it would be a resto-mod, an updated and improved version of the original, preserving its character but removing its faults. The book was originally published in 1975 which, from a 2022 perspective, seems a relatively short time after Vanwall’s demise. The co-authors were those two giants of postwar motorsport literature, Denis Jenkinson and Cyril Posthumus. Doug Nye, who is now the pre-eminent contemporary writer on this era, has updated and expanded the text, and added some 400 documents from his own archive. The new book preserves the essence of the 1975 original, but now has the added sheen of a 2022 production. Nye, who has been keeping his pencil sharp for nigh on 60 years and produced over 70 books, considers his role in this book a tribute to his old great mates and mentors, and regards it as one of his favorite titles.

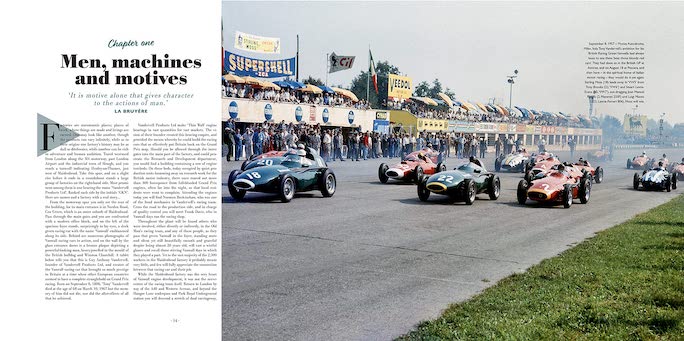

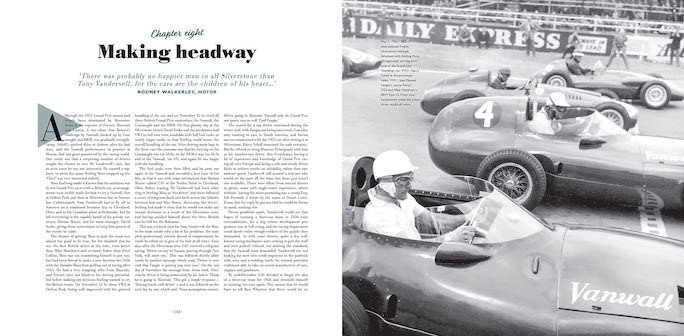

Guy Anthony “Tony Vandervell” (1898–1967) was the British businessman who famously made it his life’s work “to beat those bloody red cars” and, after spending a fortune and working his team to the bone, Vanwall’s day of days came at Aintree in the 1957 British Grand Prix, when Moss and Brooks shared the first world championship victory by an all-British team. Triumph and tragedy punctuated the team’s eventual ascent to the very first world constructors’ championship in 1958. Mike Hawthorn might have been World Drivers’ Champion that year, but Tony Vandervell had finally delivered on the promises he had first made with the green Thin Wall Special, which, ironically, had started life as one of those “bloody red cars,” a Ferrari 125.

The authors describe not only the rise and fall of Vanwall the race team, but also Tony Vandervell’s glorious industrial career, starting with, in the words of the period advertisement “A further development in thin wall bearings – the three-layer bearing . . .” The reader is left in no doubt that Vandervell’s entrepreneurship matched his engineering flair, and his career demonstrated that he was a very tough cookie indeed.

Before reading this book, I’d dismissed any depiction of Vandervell as the “English Ferrari” as lazy journalism, but it is perhaps a valid comparison. The leadership, charisma, and sheer bloody-mindedness of Enzo and Tony resonate, so much so that to identify them by forename alone feels like an impertinence. Ferrari notoriously confessed to having “killed his mother” by beating Alfa Romeo, and Vandervell didn’t hesitate to remove himself from BRM. And the chaos of the Bourne firm’s early years proved he was right. As Raymond Mays is quoted as saying, “Vandervell and I could not get on together; we both seemed to rub each other up the wrong way.” There’s pause for thought. Jenks and Posthumus’ account of the long and bumpy road that led to the glorious 1958 season is a testament to the grit and resourcefulness that Vandervell and his lieutenants applied to challenging the hegemony of the infamous red cars.

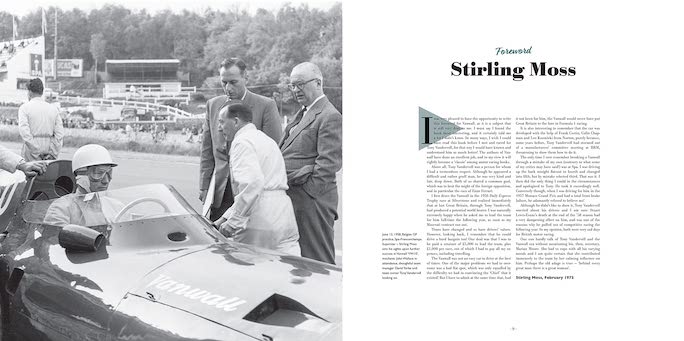

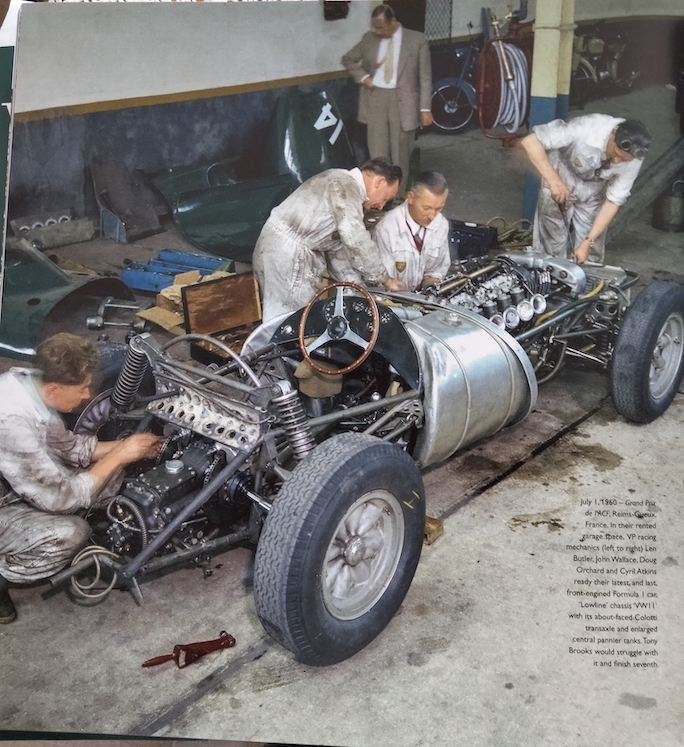

But the book is about so much more than the headline heroes. It reminds us that behind a Stirling Moss or a Tony Brooks stood a battalion of other ranks, united in their quest for British success. The photographs and ephemera elevate this book from the very good to the great and, while the race cars cannot fail to entrance, it is the depiction of the cast of supporting actors that is even more compelling. Brylcreemed hair, the crushing formality of jackets and ties, battered overalls and the ever-present cigarette—how different it all looks from the tanned and fit youngsters who make a 2022 Formula One team function. The Fifties was a different country, and you can sense the legacy of the war years in almost every face—everyone looks tired, complexions are pallid, teeth are wonky and nobody, with the possible exception of Stirling Moss, looks young, or even as if they ever had been young.

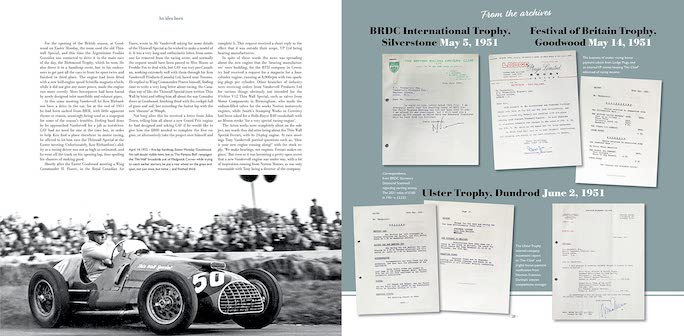

At the end of each chapter are reproductions of correspondence and other paperwork from the Vanwall archives and they add a wonderful sense of the Fifties zeitgeist. It was an era where letters were brief, formal, to the point and written in that clipped, often hectoring style that epitomized British business life. The reader can sense every emotion, from barely suppressed anger about another component failure, to frustration with a race organizer’s starting money offers, to well restrained joy at a victory. It was a world where nobody expressed concern about mental well-being and where “reaching out” involved installing a tricky suspension component.

There’s another, more intimate aspect to the ephemera which I found beguiling and moving: the first illustration in the book is of the letter which the thirteen-year-old George Harrison (yes, that one) had written to Vanwall in 1956 to request some photographs “to add to my collection.” I loved the letter dated November 1, 1956 in which one B. Morrison (“aged 19/1/4”) simply applied “for the job of racing driver” with the team; history suggests the club racer’s application was not successful. And how touchingly simple was the letter from Lodge Plugs Limited, enclosing a check for £18 as a bonus for the Thinwall Special’s second place at Goodwood; in period style the letter concludes “We trust this will meet with your satisfaction, we remain, yours faithfully.”

But the book might also challenge the assumptions a millennial F1 fan might make about the Grand Prix scene of seventy years ago. Thanks to the crippling effect of wartime debt and deprivation, the immediate postwar years for the average Brit were a time of parsimony, rationing, make-do-and-mend, and muddling through. But Tony Vandervell (dispensing “champagne and caviar at Silverstone”) wasn’t the average citizen and his team was organized as a fast-moving, agile business with eyes on the future and with every potential for advantage being pursued. The picture of a Vanwall in a wind tunnel (“to confirm that . . . body shapes matched up to Frank Costin’s theorising”), the testing of no fewer than six different fuel blends from Shell-Mex and BP in 1954, and the account of Vandervell’s trip to Modena to buy machine tools from Maserati’s Count Orsi all bear witness to the diligence and determination of the Vanwall organization. And financial firepower—the machine tools cost £10,000 (equivalent to $235,000 at 2021 prices) and represented twenty years’ wages for the average British worker.

The authors were both famous, perhaps even notorious, for their love of technical detail and the book does feature an embarrassment of technical riches, in both words and pictures. The reader can almost smell the cutting oil and hear the shouted conversations as yet another engine modification is tested to destruction. But it is to the authors’ credit—and to Doug Nye’s—that the human side of the Vanwall story isn’t neglected. I especially enjoyed the inclusion of Tony Vandervell’s crisp dismissal of Mrs. Iris Purcell’s publicly expressed public outrage that Mike Hawthorn had been excused from National Service—“I think you will be relieved when you know all the facts.”

So, once more, this is a simply wonderful book, and I am deeply grateful to the friend who insisted I read it and lent me his personal copy (No. 71 of 1000 copies, signed by Doug Nye). I have gained a new respect for those damned green cars, an insight into a decade I had unfairly dismissed as the boring warm-up act for the Technicolor Sixties and (dare I admit it?) a desire to have been Vanwall driver Harry Schell’s new best friend. What a guy he seems to have been . . .

A leather‐bound (green, what else?) Collector’s Edition of 100 copies autographed by Nye and Tony Brooks is available at £895. Its slipcase has a cylinder built into the spine that contains three collectible prints.

Copyright 2022, John Aston Speedreaders.info

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter