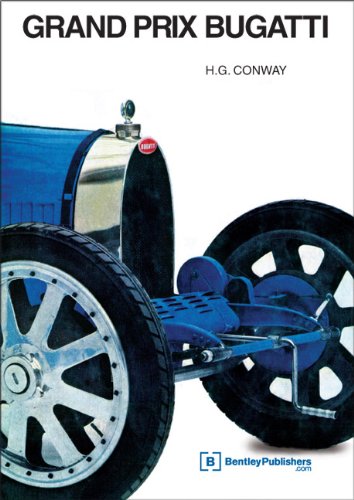

The Bugattis of Jean De Dobbeleer

by Charles Fawcett

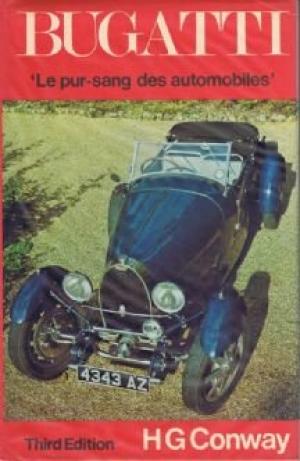

If you read the descriptions of vintage Bugattis in auction catalogs you’ll often enough encounter the name of the protagonist of this book, Jean De Dobbeleer (1918–1974), a Belgian dealer through whose Brussels showroom and garage hundreds of Bugattis passed after World War II. He dealt in other marques too and also serviced them but specialized in Bugattis and even cobbled together entire cars with NOS parts he collected directly from the factory.

Just how many Bugs precisely have a De Dobbeleer connection is not known, hundreds certainly, and at any rate enough to earn him the nickname “Mister/Monsieur Bugatti.” That he kept no records, or at least none that are known, is no surprise considering that in his day a Bugatti was just another old (the first prototype dates to 1900) or aging car with no future and limited appeal (only two types were released in the 1950s before the end in 1962) and not the blue-blood mega-dollar collectible it is today. What De Dobbeleer did do was photograph the cars, surely not out of a desire to document them but simply because he was taken by the then still relatively newfangled hobby of amateur photography; he even had his own darkroom.

And it is those images, over 400, being shown to the author in 2010 that resulted in the publication of this book. They make up the bulk of the photos gathered here. How and for what purpose De Dobbeleer’s negatives ended up in the hands of one of his US retail contacts, Lyman Greenlee (another name you’ll encounter often in the histories of important Bugattis, along with fellow US enthusiasts/dealers Gene Cesari who wrote the Foreword to this book and Selden Loring who describes his business dealings with De Dobbeleer), is not recorded. Unable to interest a museum in buying the negatives, Greenlee instead sold them to Ron Kellogg (who famously finished the build of a 1937 Bugatti Type 57/59 Roadster Special that has no original chassis number but was declared legitimate by the Bugatti Trust and assigned #128) who presides over an archive of more than a million photos and automobilia items (many for sale). It is here that author Fawcett, a serious Bugatti enthusiast since the 1950s (but not an owner) was made aware of them and, having contributed to club-level magazines, talked into thinking about publishing them in book form.

This long-winded story has a point: even this sharply abbreviated account will convey the notion that this story revolves around a small number of figures in the worldwide Bugatti scene. And it is those people, insiders for lack of a better word, who will most appreciate the existence of this book. For most anyone else, the book is far too specialized and far too devoid of contextual narrative to fulfill a “need” unless you just like to feast on period photos. With a little more text and context/breadth and depth it could have easily become a book for the coachwork and the chassis or engine folks. This is neither here nor there and merely meant to establish that if you gift this book to a general-interest car guy/gal, a look of polite incomprehension may be all the thanks you can hope for.

Fawcett scanned the photos (having first to learn how to do it) with uncontestably good results and researched De Dobbeleer’s activites by talking to people who knew him—including daughter Leda who provided the biographical information reproduced here—or had bought cars from him. Various Bugatti experts contributed details and insights, and checked data. The photos are credited and augmented with a few items of correspondence, brochures and the like.

Suitably, the book is in landscape format (9 x 12″) but, except for the chapter openers only a very few photos actually take advantage of the full page. In most cases there are several smaller ones to a page. The De Dobbeleer photos are taken inside his workshops (he moved it three times) and on the streets in front of it, and almost all of them are new to the record. In most cases the type depicted is identified, sometimes also the coachwork and the chassis number. (Note: a caption on p. 42/43 identifies a Type 57S as chassis 57511, a car that De Dobbeleer privately drove for a year before selling it on and that is also shown on p. 9 in front of his home but with different bumpers and headlights. An inquiry to the author reveals that the p. 42/43 car is actually #57523, still extant, so annotate your copy accordingly.)

After an introduction to De Dobbeleer and most of the aforementioned personages, the Bugatti coverage starts off with a survey of “The Rarest of the Rare” models and then principally branches out into touring and competition cars, with a separate section on engine and chassis parts and components. Among the rareties are the 1909 prototype Type 10, the Type 45 16-cylinder GP car, the Type 53 fwd racer, the 1937 Le Mans-winning Type 57G “Tank,” Types 64/73C/101, and a mystery single-seat racecar. Even though some narrative is devoted to these particularly special cars, newbies will find it all too scant. Some 20 pages show a random assortment of other marques at De Dobbeleer’s shop; the information provided here is minimal and partly speculative. There is a brief Bibliography; no Index.

The book is written by an enthusiast for enthusiasts—and one wants to be enthusiastic in praising it. But even a non-professional effort, given the help and resources available to it, should have been able to rein in the notable quantity of typos, missing words, and typesetting fallacies that mar so many of the pages that have text on them.

In terms of its physical properties the book is beautifully produced and a joy to handle. To the restorer, not to mention the lucky present-day owner, period photos are always of inestimable importance, and those people will know what they’re looking for/at even in the absence of in-depth descriptions.

Copyright 2012, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter