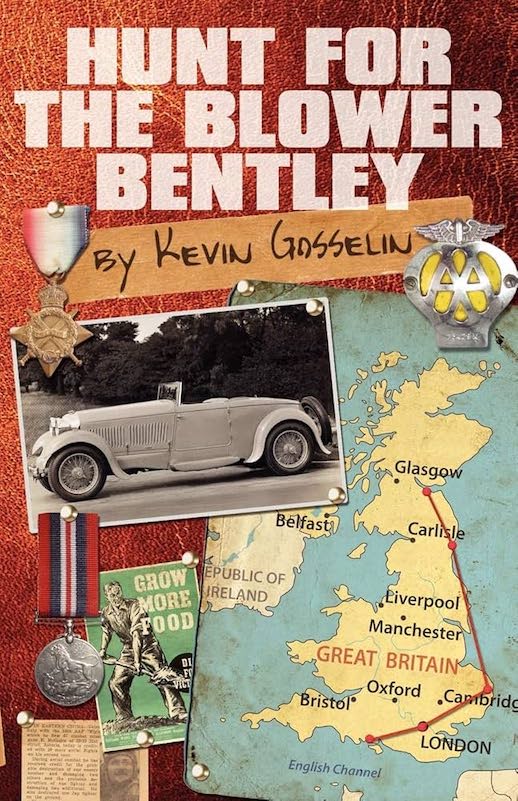

Hunt for the Blower Bentley

by Kevin Gosselin

by Kevin Gosselin

“To supercharge a Bentley engine was to pervert its design and corrupt its performance.”

—W.O. Bentley

By the time Bentley Motors’ founder muttered these words he no longer had the final word in the affairs of his company.

Maybe it was his background in railway engineering that made him favor the more mechanically straightforward approach to making a car faster: increase the engine’s displacement instead of supercharging it. He predicted nothing but doom for this approach but had no choice but to follow his Managing Director’s marching orders (Woolf Barnato, one of the fabled Bentley Boys who came from a South African diamond fortune) to build five “Blowers” for fellow Bentley Boy and acclaimed British racer Sir Henry “Tim” Birkin whom even W.O. Bentley described as “the greatest Briton of his time.”

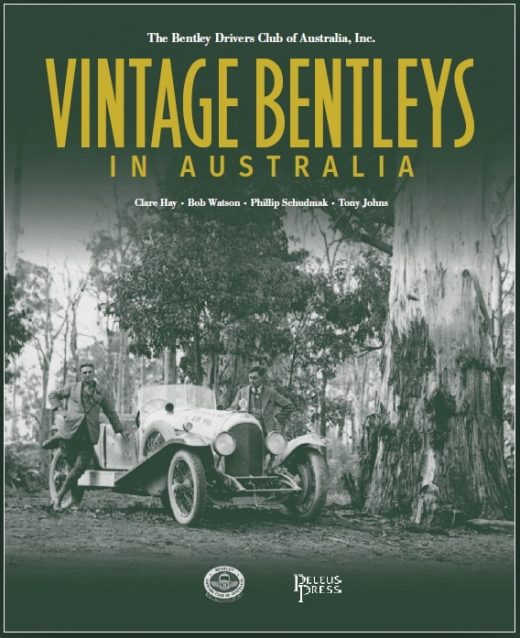

To get racecars certified, Bentley had to build homologation models, and so 50 production cars were erected. These cars were desirable in their day—even, and just as W.O. had predicted, without noteworthy racing success—and today genuine supercharged Bentleys are as rare as hen’s teeth. Every iota of history of all the Blowers has been meticulously recorded—except for one car that dropped off the radar within only a few years and has never been heard of since: chassis SM3912 built in 1930/31 and last heard of in 1939.

That is the car at the center of this multi-layered novel, author Kevin Gosselin’s second adventure for his Connecticut innkeeper cum “automotive archaeologist” Faston Hanks. If that name sounds familiar you may have made his acquaintance in the first book, Hunt for 901 (ISBN-13: 978-0978956325, 2008), which concerns itself with the search for an elusive Porsche prototype. Much like his gourmet chef creator, Hanks too is a foodie and both novels make frequent reference to that. Gosselin considers this second novel “many, many times better a book” in terms of pace and plot density—and downsized appetite.

Alternating between WWII and the present day, the novel weaves together different facets of the story: the spy who towards the end of the war flogs his Blower across England in pursuit of his nefarious business, the car going to ground, a replica being built by an enterprising soul who smells a big profit in pulling a lost car from his hat, and Hanks figuring it all out. In other words, all the makings of a perfectly good yarn. But . . .

It is a terribly harsh thing to say but it will be obvious to anyone with a brain that Gosselin—who is an automotive journalist and award-winning copywriter—gives no evidence of trying very hard to get details right. How hard, for instance, would it be to pick either British or American English and then stick with it, at least in one and the same paragraph [cf p. 41]? And why not make an effort to get the name of a coachbuilder right? It’s not Van den Plas, the ca. 1902–1949 Belgian firm but that of its English offshoot (1913–1960) that did business as Vanden Plas (abbreviated VdP, not VDP). Why describe the car’s body as made of “fabric” and a few sentences later as “leather”? These are easy things to research! Moving from hard fact to conjecture: If you follow automotive TV shows—or know your Le Mans history well—you’ll recognize the name of Alain de Cadenet. Is he the inspiration for Gosselin’s car expert “Blaine de Badenet”?

Gosselin did trouble himself to actually go look at a 4½L Bentley in his neck of the woods (Colorado) to familiarize himself with its basic workings. That would be the car in the collection of novelist/deep sea explorer Clive Cussler that Bentley folks know to be chassis FB3323. They would also know that Gosselin referring to it in the Acknowledgments as a “real Blower” must not be taken literally since this 1929 car was originally unblown (engine no. FB3323, later replaced with KM3078 from chassis KM3076) and only in 1990 received a supercharger. He also communicated with the repository for all things Bentley, the Bentley Drivers Club (whose name, incidentally, he misspells, along with that of its Foundation).

All of the above is intentionally picking nits—in which we take no joy—because there are, by any objective measure, nits to pick! And we haven’t even mentioned the buckets of typos. Getting it right is not rocket science. An author who has the urge to put a book into the world must be expected to stand and fall with the quality of his work.

Others have had the urge to call this novel a “thriller” and “nail-biter” and “pure magic.” What sheltered lives some live. All we will say is that it does have its moments.

Copyright 2012, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter